Sociology of Religion (book)

German book on sociology by Max Weber

(Redirected from Sociology of Religion)

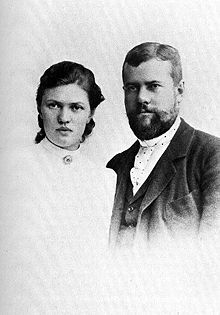

Sociology of Religion is a monograph written by Max Weber. It was published in 1922 as part of a posthumous collection of writings titled Economy and Society. The quotes below are from a translation by Ephraim Fischoff, published by Beacon Press in 1963.

Quotes

edit- The prophets ... hurled their "woe be unto you" against those who oppressed and enslaved the poor, those who joined field to field, and those who deflected justice by bribes. These were the typical actions leading to class stratification everywhere in the ancient world, and were everywhere intensified by the development of the city-state (polis).

- p. 50

- It is characteristic of the prophets that they do not receive their mission from any human agency, but seize it.

- p. 51

- As intellectualism suppresses belief in magic, the world’s processes become disenchanted, lose their magical significance, and henceforth simply “are” and “happen” but no longer signify anything. As a consequence, there is a growing demand that the world and the total pattern of life be subject to an order that is significant and meaningful.

The conflict of this requirement of meaningfulness with the empirical realities of the world and its institutions, and with the possibilities of conducting one’s life in the empirical world, are responsible for the intellectual’s characteristic flights from the world.- p. 125

- It is above all the impersonal and economically rationalized (but for this very reason ethically irrational) character of purely commercial relationships that evokes the suspicion, never clearly expressed but all the more strongly felt, of ethical religions. For every purely personal relationship of man to man, of whatever sort and even including complete enslavement, may be subjected to ethical requirements and ethically regulated. This is true because the structures of these relationships depend upon the individual wills of the participants, leaving room in such relations for manifestations of the virtue of charity. But this is not the situation in the realm of economically rationalised relationships, where personal control is exercised in inverse ratio to the degree of rational differentiation of the economic structure.

- pp. 216-217

- In this rationalized economic world of capitalism, not only do the requirements of religious charity founder against the refractoriness and unreliability of particular individuals, which happens in all systems, but they actually lose their meaning altogether. Religious ethics is confronted by a world of depersonalized relationships which for fundamental reasons cannot submit to even the primary norms of religious ethics. Consequently, priesthoods have always, in an interesting shift of roles and also in the interests of traditionalism, protected patriarchalism against impersonal relationships of dependence.

- p. 217

- The more a religion is aware of its opposition in principle to economic rationalization as such, the more apt are the religion’s virtuosi to reject the world, especially its economic activities.

- p. 217

- The wide chasm separating the inevitabilities of economic life from the Christian ideal ... kept the most devout groups and all those with the most consistently developed ethics far from the life of trade.

- pp. 219-220

- The fact that people with rigorous ethical standards simply could not take up a business career was not altered by the dispensation of indulgences, nor by the extremely lax principles of the Jesuit probabilistic ethics after the Counter Reformation. A business career was only possible for those who were lax in their ethical thinking.

- p. 220

- The foundering of the postulate of brotherly love in its collision with the loveless realities of the economic domain once it became rationalized led to the expansion of love for one’s fellow man until it came to require a completely unselective generosity. Such unselective generosity did not inquire into the reason and outcome of absolute self-surrender, into the worth of the person soliciting help, or into his capacity to help himself. It asked no questions, and quickly gave a shirt when a cloak had been asked for in mystical religions, the individual for whom the sacrifice is made is regarded in the final analysis as unimportant and fungible, his individual value is negated. One’s fellow man is simply a person whom one happens to encounter along the way, he has significance only because of his need and his solicitation This results in a distinctively mystical flight from the world which takes the form of a non-specific and loving self-surrender, not for the sake of the man but for the sake of the surrender itself — what Baudelaire has termed “the sacred prostitution of the soul.”

- pp. 221-222

- Wherever communal religions have rejected all employment of force as an abomination to god and have sought to require their members’ avoidance of all contact with violence, without however reaching the consistent conclusion of absolute flight from the world, the conflict between religion and politics has led either to martyrdom or to passive anti-political sufferance of the coercive regime.

- p. 228

- The true intent of the New Testament verse about “rendering unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s” is not the meaning deduced by modem harmonizing interpretations, namely a positive recognition of the obligation to pay taxes, but rather the reverse, an absolute indifference to all the affairs of the mundane world.

- p. 231

- The denunciation of wealth in the prophetic books, the Psalms, the Wisdom Literature, and subsequent writings was evoked by the social injustices which were so frequently perpetrated against fellow Jews in connection with the acquisition of wealth and in violation of the spirit of the Mosaic law.

- p. 247