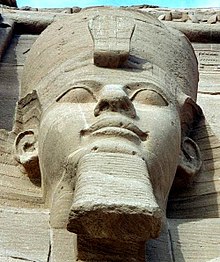

Ramesses II

Egyptian third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty

Ramesses II (c. 1303 – 1213 BC), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was an Egyptian pharaoh. He was the third ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty. Along with Thutmose III of the Eighteenth Dynasty, he is often regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the New Kingdom, which itself was the most powerful period of ancient Egypt. He is also widely considered one of ancient Egypt's most successful warrior pharaohs, conducting no fewer than 15 military campaigns, all resulting in victories, excluding the Battle of Kadesh, generally considered a stalemate. In Greek sources he is often called Sesostris or Ozymandias.

Inscriptions

edit- The Asiatic War

- Official Record of the Battle of Kadesh

- Lo, while his majesty sat talking with the princes, the vanquished chief of Kheta came and the numerous countries, which were with him. They crossed over the channel on the south of Kadesh, and charged into the army of his majesty while they were marching, and not expecting it. Then the infantry and chariotry of his majesty retreated before them, northward to the place where his majesty was. Lo, the foes of the vanquished chief of Kheta surrounded the bodyguard of his majesty, who were by his side.

- [The Attack of the Asiatics]

- When his majesty saw them, he was enraged against them, like his father, Montu, lord of Thebes. He seized the adornments of battle, and arrayed himself in his coat of mail. He was like Baal in his hour. Then he betook himself to his horses, and led quickly on, being alone by himself. He charged into the foes of the vanquished chief of Kheta, and the numerous countries which were with him. His majesty was like Sutekh, the great in strength, smiting and slaying among them; his majesty hurled them headlong, one upon another into the water of the Orontes.

- [Ramses' Personal Attack]

- "I charged all countries, while I was alone, my infantry and my chariotry having forsaken me. Not one among them stood to turn about. I swear, as Re loves me, as my father, Atum, favors me, that, as for every matter which his majesty has stated, I did it in truth, in the presence of my infantry and my chariotry."

- [Ramses' Own Statement]

- Building Inscriptions

- The Ramesseum

- Ramses II; he made (it) as his monument for his father, Amon-Re, making for him a great and august broad-hall of fine white sandstone, its nave of great flower-columns, surrounded by bud-columns: a place of rest for the lord of gods at his beautiful "Feast of the Valley"; that he might, through him, be given life ——— shaping his sacred barque like the horizon-god, founding daily offerings, doing the things which please his father, causing that his house should be for him like Thebes, supplied with every good thing, granaries reaching heaven, an august treasury containing silver, gold, royal linen, every real costly stone, which King Ramses II brought for him.

- [Dedication on the architraves of the Ramesseum]

Greek sources

edit- This king, said the priests, set out with a fleet of long ships from the Arabian Gulf and subdued all the dwellers by the Red Sea, till as he sailed on he came to a sea which was too shallow for his vessels. After returning thence back to Egypt, he gathered a great army (according to the story of the priests) and marched over the mainland, subduing every nation to which he came. When those that he met were valiant men and strove hard for freedom, he set up pillars in their land whereon the inscription showed his own name and his country's, and how he had overcome them with his own power; but when the cities had made no resistance and been easily taken, then he put an inscription on the pillars even as he had done where the nations were brave; but he drew also on them the privy parts of a woman, wishing to show clearly that the people were cowardly.

- He marched over the country doing this until he had crossed over from Asia to Europe and defeated the Scythians and Thracians. Thus far and no farther, I think, the Egyptian army went; for the pillars can be seen standing in their country, but in none beyond it. From there, he turned around and went back home; and when he came to the Phasis river, that King, Sesostris, may have detached some part of his army and left it there to live in the country (for I cannot speak with exact knowledge), or it may be that some of his soldiers grew weary of his wanderings, and stayed by the Phasis.

- Now when this Egyptian Sesostris (so the priests said) reached Daphnae of Pelusium on his way home, leading many captives from the peoples whose lands he had subjugated, his brother, whom he had left in charge in Egypt, invited him and his sons to a banquet and then piled wood around the house and set it on fire. When Sesostris was aware of this, he at once consulted his wife, whom (it was said) he had with him; and she advised him to lay two of his six sons on the fire and make a bridge over the burning so that they could walk over the bodies of the two and escape. This Sesostris did; two of his sons were thus burnt but the rest escaped alive with their father.

- This king also (they said) divided the country among all the Egyptians by giving each an equal parcel of land, and made this his source of revenue, assessing the payment of a yearly tax. And any man who was robbed by the river of part of his land could come to Sesostris and declare what had happened; then the king would send men to look into it and calculate the part by which the land was diminished, so that thereafter it should pay in proportion to the tax originally imposed. From this, in my opinion, the Greeks learned the art of measuring land; ...

- Sesostris was the only Egyptian king who also ruled Ethiopia. To commemorate his name, he set before the temple of Hephaestus two stone statues of himself and his wife, each thirty cubits high, and statues of his four sons, each of twenty cubits. Long afterwards Darius the Persian would have set up his statue before these; but the priest of Hephaestus forbade him, saying that he had achieved nothing equal to the deeds of Sesostris the Egyptian; for Sesostris (he said) had subdued the Scythians, besides as many other nations as Darius had conquered, and Darius had not been able to overcome the Scythians; therefore it was not just that Darius should set his statue before the statues of Sesostris, whose achievements he had not equalled. Darius, it is said, let the priest have his way.

- Herodotus, Histories 2. 102, 103, 107, 109, 110. Translated by A. D. Godley (1922–1925)

- Ten stades from the first tombs, he says, in which, according to tradition, are buried the concubines of Zeus, stands a monument of the king known as Osymandyas. At its entrance there is a pylon, constructed of variegated stone, two plethra in breadth and forty-five cubits high; passing through this one enters a rectangular peristyle, built of stone, four plethra long on each side; it is supported, in place of pillars, by monolithic figures sixteen cubits high, wrought in the ancient manner as to shape; and the entire ceiling, which is two fathoms wide, consists of a single stone, which is highly decorated with stars on a blue field. Beyond this peristyle there is yet another entrance and pylon, in every respect like the one mentioned before, save that it is more richly wrought with every manner of relief; beside the entrance are three statues, each of a single block of black stone from Syene, of which one, that is seated, is the largest of any in Egypt, the foot measuring over seven cubits, while the other two at the knees of this, the one on the right and the other on the left, daughter and mother respectively, are smaller than the one first mentioned. And it is not merely for its size that this work merits approbation, but it is also marvellous by reason of its artistic quality and excellent because of the nature of the stone, since in a block of so great a size there is not a single crack or blemish to be seen. The inscription upon it runs: "King of Kings am I, Osymandyas. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works." There is also another statue of his mother standing alone, a monolith twenty cubits high, and it has three diadems on its head, signifying that she was both daughter and wife and mother of a king.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, 1. 47. Translated by C. H. Oldfather (1933)

Mummy

edit- On the temples there are a few sparse hairs, but at the poll the hair is quite thick, forming smooth, straight locks about five centimeters in length. White at the time of death, and possibly auburn during life, they have been dyed a light red by the spices (henna) used in embalming ... the moustache and beard are thin. ... The hairs are white, like those of the head and eyebrows ... the skin is of earthy brown, splotched with black ... the face of the mummy gives a fair idea of the face of the living king.

- Gaston Maspero, Egyptian Archaeology (1892), pp. 76–77.

Legacy

edit- I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert . . . near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings;

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.- P. B. Shelley, "Ozymandias", The Examiner (11 January 1818)

- In Egypt’s sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desert knows:—

“I am great OZYMANDIAS,” saith the stone,

“The King of Kings; this mighty City shows

The wonders of my hand.”—The City’s gone,—

Naught but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder,—and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro’ the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.- Horace Smith, The Examiner (1 February 1818); "On A Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below", Amarynthus, &c. (1821)

Sources

edit- Breasted, J. H. (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt. Vol. 3. University of Chicago Press.