Photography

art, science, and practice of creating durable images by recording light or other electromagnetic radiation

(Redirected from Photographers)

Photography is the art, science, and practice of creating durable images by recording light or other electromagnetic radiation, either chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film, or electronically by means of an image sensor

Quotes

edit- Quotes are arranged alphabetically by author

A - F

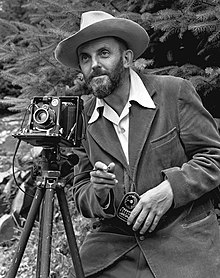

edit- There are no rules for good photographs, there are only good photographs.

- Ansel Adams as cited in: Elizabeth T. Schoch (2002) The everything digital photography book. p. 105

- A great photograph is a full expression of what one feels about what is being photographed in the deepest sense, and is, thereby, a true expression of what one feels about life in its entirety.

- Ansel Adams "A Personal Credo" (1943), published in American Annual of Photography (1944), reprinted in Nathan Lyons, editor, Photographers on Photography (1966), reprinted in Vicki Goldberg, editor, Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present (1988)

- I have often thought that if photography were difficult in the true sense of the term — meaning that the creation of a simple photograph would entail as much time and effort as the production of a good watercolor or etching — there would be a vast improvement in total output. The sheer ease with which we can produce a superficial image often leads to creative disaster.

- Ansel Adams "A Personal Credo" (1943), published in American Annual of Photography (1944), reprinted in Nathan Lyons, editor, Photographers on Photography (1966), reprinted in Vicki Goldberg, editor, Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present (1988)

- It shows an image that could only have been produced photographically.

- Nicholas Allen, as quoted in Is The Shroud of Turin a Medieval Photograph? A Critical Examination of the Theory by Barrie M. Schwortz

- Photographs deceive time, freezing it on a piece of cardboard where the soul is silent.

- Isabel Allende Of Love and Shadows (1984)

- Pictures produced by camera can resemble paintings or drawings in presenting recognizable images of physical objects. But they have also characteristics of their own, of which the following two are relevant here: first the photograph acquires some of its unique visual properties through the technique of mechanical recording; and second, it supplies the viewer with a specific kind of experience, which depends on his being aware of the picture's mechanical origin. To put it more simply: (1) the picture is coproduced by nature and man and in some ways looks strikingly like nature, and (2) the picture is viewed as something being by nature.

- Rudolf Arnheim (1974). "On the nature of Photography", Critical Inquiry, Vol.1, n.1, p. 156; As cited in: A. Bianchin (2007), "Theoretical Cartography Issues in the face of New Representation"

- In photography everything is so ordinary; it takes a lot of looking before you learn to see the ordinary.

- David Bailey in interview in The Face December 1984

- Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organisation of forms which give that event its proper expression.

- Henri Cartier-Bresson as cited in: Bruce Elder (1989) Image and identity: reflections on Canadian film and culture. p. 114

- Two studies investigated gender stereotyping in American magazine photos. Study 1 compares cover photos of men and women on face-ism, an index of the degree to which a photo focuses on the face versus the body. Photos of women are found to focus more on their bodies and photos of men on their faces, a finding consistent with previous research. This finding is strongly mediated by other variables, however, particularly the social role of the cover person. Study 2 compares the facial expressions, specifically the mouth positions, of men and women in advertisements from several popular magazines. Women are significantly more likely than men to be photographed with their mouths open, presumably portraying less serious expressions.

- Dodd, D. K., Harcar, V., Foerch, B. J., Anderson, H. T. (1989). "Face-ism and facial expressions of women in magazine photos", The Psychological Record, 39, p. 325.

- Black and white are the colors of photography. To me, they symbolize the alternatives of hope and despair to which mankind is forever subjected. Most of my photographs are of people; they are seen simply, as through the eyes of the man in the street. There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment. This kind of photography is realism.

- Robert Frank, in: Nathan Lyons, Photographers on photography: a critical anthology, (1966), p. 66

- Life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference and it is important to see what is invisible to others.

- Robert Frank, cited in: Robet Hirsch, Photographic Possibilities, 2009, p. ix

G - L

edit- You put your camera around your neck in the morning, along with putting on your shoes, and there it is, an appendage of the body that shares your life with you. The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.

- Dorothea Lange, as quoted in Dorothea Lange : A Photographer's Life (1978), p. vii

- One should really use the camera as though tomorrow you'd be stricken blind. To live a visual life is an enormous undertaking, practically unattainable. I have only touched it, just touched it.

- Dorothea Lange, as quoted in Dorothea Lange: A Visual Life (1994) by Elizabeth Partridge

M - R

edit- It was October 1966 and the new development of the new satellite system, Hexagon, was underway. The project was a follow-on to very successful Corona satellite program and a complement to the higher-resolution Gambit satellite.

All these programs required 315,000 feet of film to be dropped in re-entry vehicles from orbit and retrieved in mid-air by U.S. forces. Gambit and Hexagon were declassified late this year, and its engineers were profiled this week by the Associated Press.- Alexis C. Madrigal, "TOP SECRET: Your Briefing on the CIA's Cold-War Spy Satellite, 'Big Bird'", (Dec 29, 2011).

- From 1971 to 1986 a total of 20 satellites were launched, each containing 60 miles (100 kilometers) of film and sophisticated cameras that orbited the earth snapping vast, panoramic photographs of the Soviet Union, China and other potential foes. The film was shot back through the earth's atmosphere in buckets that parachuted over the Pacific Ocean, where C-130 Air Force planes snagged them with grappling hooks.

- Alexis C. Madrigal, "TOP SECRET: Your Briefing on the CIA's Cold-War Spy Satellite, 'Big Bird'", (Dec 29, 2011).

- The photograph extends and multiplies the human image to the proportions of mass-produced merchandise. The movie stars and matinee idols are put in the public domain by photography. They become dreams that money can buy.

- Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), p. 257

- The step from the age of Typographic Man to the age of Graphic Man was taken with the invention of photography.

- Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), p. 259

- The photograph has reversed the purpose of travel, which until now had been to encounter the strange and unfamiliar. ... The world itself becomes a sort of museum of objects that have been encountered before in some other medium.

- Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), pp. 267-268

- The image (shadow) being inverted depends on there being an aperture at the cross-over and the image (shadow) being distant. The explanation lies in the aperture.

The image (shadow): The light reaches the person shining like an arrow. The lowest [light] that reaches the person is the highest [in the image] and the highest [light] that reaches the person is the lowest [in the image]. The feet conceal the lowest light and therefore become the image (shadow) at the top. The head conceals the highest light and therefore becomes the image (shadow) at the bottom.- Mozi Book 10: Exposition of Canon II; this is the earliest known description of the inverted image produced by a camera obscura,; as translated in by Ian Jonston in The Mozi (2010), p. 489

- Photography is a strong tool, a propaganda device, and a weapon for the defense of the environment... Photographs are believed more than words; thus they can be used persuasively to show people who have never taken the trouble to look what is there. They can point out beauties and relationships not previously believed or suspect to exist.

- Eliot Porter as cited in: Rebecca Solnit (2007) Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics. p. 235

"Fetal Images: The Power of Visual Culture in the Politics of Reproduction" (1987)

editPetchesky, Rosalind Pollack (1987). "Fetal Images: The Power of Visual Culture in the Politics of Reproduction". Feminist Studies. 13 (2): 263–292. doi:10.2307/3177802. JSTOR 3177802. S2CID 41193716.

- In the mid-1980s, with the United States Congress still deadlocked over the abortion issue and the Supreme Court having twice reaffirmed “a woman’s right to choose,” the political attack on abortion rights moved further into the terrain of mass culture and imagery. Not that the “pro life movement” has abandoned conventional political arenas; rather, it defeat there have hardened its commitment to a more long-term ideological struggle over the symbolic meanings of fetuses, dead or alive.

Antiabortionists in both the United States and Britain have long applied the principle that a picture of a dead fetus is worth a thousand words. Chaste silhouettes of the fetal form, of voyeuristic necrophilic photographs of its remains, litter the background of any abortion talk. These still images float like spirits through the courtrooms, where lawyers argue that fetuses can claim tort liability; through the hospitals and clinics, where physicians welcome them as "patients"; and in front of all the abortion centers, legislative committees, bus terminals, and other places that" right-to-lifers" haunt. The strategy of antiabortionists to make fetal personhood a self-fulfilling prophecy by making the fetus a public presence addresses a visually oriented culture. Meanwhile, finding "positive" images and symbols of abortion hard to imagine, feminists and other prochoice advocates have all too readily ceded the visual terrain.- pp.263-264

- The most disturbing thing about how people receive The Silent Scream, and indeed all the dominant fetal imagery, is their apparent acceptance of the image itself as an accurate representation of a real fetus. The curled-up profile, with its enlarged head and fin like arms, suspended in its balloon of amniotic fluid, is by now so familiar that not even most feminists question its authenticity (as opposed to its relevance).I went back to trace the earliest appearance of these photos in popular literature and found it in the June 1962 issue of Look (along with Life, the major mass-circulating "picture magazine" of the period). It was a story publicizing a new book, The First Nine Months of Life, and it featured the now-standard sequel of pictures at one day, one week, seven weeks, and so forth. In every picture the fetus is solitary, dangling in the air (or its sac) with nothing to connect it to any life-support system but "a clearly defined umbilical cord. "In every caption it is called "the baby"(even at forty-four days) and is referred to as "he"-until the birth, that is, when "he" turns out to be a girl. Nowhere is there any reference to the pregnant woman, except in a single photograph at the end showing the newborn baby lying next to the mother, both of them gazing off the page, allegedly at "the father."From their beginning, such photographs have represented the fetus as primary and autonomous, the woman as absent or peripheral.

- p.268

- Fetal imagery epitomizes the distortion inherent in all photographic images: their tendency to slice up reality into tiny bits wrenched out of real space and time. The origins of photography can be traced to late-nineteenth-century Europe's cult of science, itself a by-product of industrial capitalism. Its rise is inextricably linked with positivism, that flawed epistemology that sees "reality" as discrete bits of empirical data divorced from historical process or social relationships. Similarly, fetal imagery replicates the essential paradox of photographs whether moving or still, their "constitutive deception" as noted by postmodernist critics: the appearance of objectivity, of capturing" literal reality." As Roland Barthes puts it, the "photographic message" appears to be "a message without a code." According to Barthes, the appearance of the photographic image as "a mechanical analogue of reality, "without art or artifice, obscures the fact that that image is heavily constructed, or "coded"; it is grounded in a context of historical and cultural meanings.

Yet the power of the visual apparatus's claim to be "an unreasoning machine" that produces" an unerring record"(the French word for "lens" is l'object if) remains deeply embedded in Western culture. This power derives from the peculiar capacity of photographic images to assume two distinct meanings, often simultaneously: an empirical (informational) and a mythical (or magical) meaning. Historically, photographic imagery has served not only the uses of scientific rationality-as in medical diagnostics and record keeping-and the tools of bureaucratic rationality-in the political record keeping and police surveillance of the state. Photographic imagery has also, especially with the "democratization" of the hand-held camera and the advent of the family album, become a magical source of fetishes that can resurrect the dead or preserve lost love. And it has constructed the escape fantasy of the movies. This older, symbolic, and ritualistic (also religious?) function lies concealed within the more obvious rationalistic one.- pp.268-269

- The double text of The Silent Scream, noted earlier, recapitulates this historical paradox of photographic images: their simultaneous power as purveyors of fantasy and illusion yet also of "objectivist 'truth."' "'When Nathanson claims to be presenting an abortion from the "vantage point of the [fetus],"the image's appearance of seamless movement through real time-and the technologic allure of the video box, connoting at once "advanced medicine" and "the news"-render his claim "true to life." Yet he also purveys a myth, for the fetus-if it had any vantage point-could not possibly experience itself as if dangling in space, without a woman's uterus and body and bloodstream to support it.

In fact, every image of a fetus we are shown, including The Silent Scream, is viewed from the standpoint neither of the fetus nor of the pregnant woman but of the camera. The fetus as we know it is a fetish. Barbara Katz Rothman observes that "the fetus in utero has become a metaphor for 'man' in space, floating free, attached only by the umbilical cord to the spaceship. But where is the mother in that metaphor? She has become empty space."' Inside the futurizing spacesuit, however, lies a much older image. For the autonomous, free-floating fetus merely extends to gestation the Hobbesian view of born human beings as disconnected, solitary individuals. It is this abstract individualism, effacing the pregnant woman and the fetus's dependence on her, that gives the fetal image its symbolic transparency, so that we can read in it ourselves, our lost babies, our mythic secure past.- pp.269-270

- Evidentiary uses of photographic images are usually enlisted in the service of some kind of action-to monitor, control, and possibly intervene.

- p.274

- How different women see fetal images depends on the context of the looking and the relationship of the viewer to the image and what it signifies. Recent semiotic theory emphasizes "the centrality of the moment of reception in the construction of meanings." The meanings of a visual image or text are created through an "interaction" process between the viewer and the text, taking their focus from the situation of the viewer. John Berger identifies a major contextual frame defining the relationship between viewer and image in distinguishing between what he calls "photographs which belong to private experience" and thus connect to our lives in some intimate way, and "public photographs," which excise bits of information "from all lived experience." Now, this is a simplistic distinction because "private" photographic images become imbued with "public" resonances all the time; we "see" lovers' photos and family albums through the scrim of television ads. Still, I want to borrow Berger's distinction because it helps indicate important differences between the meanings of fetal images when they are viewed as "the fetus" and when they are viewed as "my baby.”

- pp.280-281

- When legions of right-wing women in the antiabortion movement brandish pictures of gory dead or dreamlike space-floating fetuses outside clinics or in demonstrations, they are participating in a visual pageant that directly degrades women- and thus themselves. Wafting these fetus-pictures as icons, literal fetishes, they both propagate and celebrate the image of the fetus as autonomous space-hero and the pregnant woman as "empty space." Their visual statements are straight forward representations of the antifeminist ideas they (and their male cohorts) support. Such right-wing women promote the public, political character of the fetal image as a symbol that condenses a complicated set of conservative values-about sex, motherhood, teenage girls, fatherhood, the family. In this instance, perhaps it makes sense to say they participate "vicariously" in a "phallic" way of looking and thus become the "complacent facilitators for the working out of man's fantasies."

- p.281

- Women's responses to fetal picture taking may have another side as well, rooted in their traditional role in the production of family photographs. If photographs accommodate "aesthetic consumerism," becoming instruments of appropriation and possession, this is nowhere truer than within family life-particularly middle-class family life. Family albums originated to chronicle the continuity of Victorian bourgeois kin networks. The advent of home movies in the 1940s and 1950s paralleled the move to the suburbs and backyard barbecues. Similarly, the presentation of a sonogram photo to the dying grandfather, even before his grandchild's birth, is a 1980s' way of affirming patriarchal lineage. In other words, far from the intrusion of an alien, and alienating, technology, it may be that ultrasonography is becoming enmeshed in a familiar language of "private" images.

Significantly, in each of these cases it is the woman, the mother, who acts as custodian of the image- keeping up the album, taking the movies, presenting the sonogram. The specific relationship of women to photographic images, especially those of children, may help to explain the attraction of pregnant women to ultrasound images of their own fetus (as opposed to "public" ones). Rather than being surprised that some women experience bonding with their fetus after viewing its image on a screen (or in a sonographic "photo"), perhaps we should understand this as a culturally embedded component of desire. If it is a form of objectifying the fetus (and the pregnant woman herself as detached from the fetus), perhaps such objectification and detachment are necessary for her to feel erotic pleasure in it. If with the ultrasound image she first recognizes the fetus as "real," as "out there," this means that she first experiences it as an object she can possess.- p.283

S - Z

edit- [U]tilizing the discoveries of scientists, photography was invented by artists for the use of artists. ...Daguerre had acquired a considerable reputation as a painter and inventor of illusionist effects in panoramas and... as a designer of stage settings... Almost at the same time as he invented the diorama... Daguerre began to experiment with the photographic process. ...[H]e would have to be considered... the first artist to utilize photographs for his paintings—before photography was in effect discovered.

...Talbot, the discoverer of another photographic process, was an amateur artist who used the camera lucida and camera obscura from the early 1820s as aids to his landscape drawings. Among other... near-discoverers of photography were artists who sought through the camera obscura... the last word in art.

...Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce succeeded in fixing what he called a heliograph on glass. Niépce and his son... a painter and sculptor, had been practicing the new art of lithography... Because the litho stones of good quality were difficult to obtain, they... substituted pewter plates. ...[T]he elder Niépce ...conceived of the idea of recording, photographically, [using as negatives, existing paper engravings made transparent by oiling or waxing] an image on the plate and etching it for printing. ...After unsuccessful experiments with chloride of silver, he used another light-sensitive substance called bitumen of judea; the unexposed parts could be dissolved, baring the metal to be etched ...By 1837, with common salt as a fixative, Daguerre made his first relatively permanent photograph...- Aaron Scharf, Art and Photography (1968) pp. 5-6.

- When [Talbot] learned of Daguerre's achievement he promptly published... 'Photogenic Drawing' . During ...1839, after Dagurerre's and Talbot's discoveries had been advertised, other inventors ...appeared ...One claim indicated that certain artists ...thirty years previously, had developed a negative process using diluted nitric acid as a fixative, ...It had not, it seems, occurred to them, as later it did to Talbot, to make the negative translucent and re-photograph it. ...Whereas the daguerreotype was a direct positive process, each photograph a unique image on a ...polished metal plate, photogenic drawing was ...to develop into a negative-positive one allowing for multiple copies ...Talbot's ...calotypes, were printed from oiled or waxed paper negatives. They thus reproduced the fibrous texture [image distortion] of the paper ...Talbot believed that the photograph would become an important aid to artists... the multitude of minute details ...'no artist would take the trouble to copy faithfully from nature'. Talbot wrote this in 1844 in his ...The Pencil of Nature, the first publication using actual photographic prints in conjuction with text.

- Aaron Scharf, Art and Photography (1968) p. 9. Note: Talbot presented his paper, "Some Account of the art of Photogenic Drawing, or the process by which natural objects may be made to delineate themselves without the aid of the artist's pencil" (Jan. 31, 1839) to the Royal Society, as noted in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London.

- Inevitably, the untenable relation between naturalistic art and photography became clear. However much other factors may have contributed to the character of Impressionist painting, to photography must be accorded some special consideration. The awareness of the need for personal expression in art increased in proportion to the growth of photography and a photographic style in art. The evolution of Impressionist painting towards colours one ought to see, and the increased emphasis on matière [material], can well be attributed to the encroachment of photography on naturalistic art. Impressionist paintings may be seen as mirrors of nature, but above all they convey the idea that they are paintings of nature.

- Aaron Scharf, Art and Photography (1968) p. 138.

- A photograph is a biography of a moment.

- Art Shay as cited in interview: Dean Reynalds (2014 February 13) Photographs tell story of decades-long romance. CBS News.

- Photography is more than a means of recording the obvious. It is a way of feeling, of touching, of loving. What you have caught on film is captured forever, whether it be a face or a flower, a place or a thing, a day or a moment. The camera is a perfect companion. It makes no demands, imposes no obligations. It becomes your notebook and your reference library, your microscope and your telescope. It sees what you are too lazy or too careless to notice, and it remembers little things, long after you have forgotten everything.

- Aaron Siskind, cited in: The Amateur Photographer's Handbook, (1973), p. vi

- Photography records the gamut of feelings written on the human face, the beauty of the earth and skies that man has inherited, and the wealth and confusion man has created. [It is] a major force in explaining man to man.

- Edward Steichen, quoted in Time Magazine, "To Catch the Instant", 7 April 1961

- Today, I am no longer concerned with photography as an art form. I believe it is potentially the best medium for explaining man to himself and his fellow man.

- Edward Steichen (1967), cited in: National Portrait Gallery (Smithsonian Institution), Carolyn Kinder Carr, National Portrait Gallery (Great Britain) (2003). Americans: paintings and photographs from the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, Deel 3. p. 207

- Photography as a fad is well-nigh on its last legs, thanks principally to the bicycle craze.

- Alfred Stieglitz (1887) in the American Annual of Photography 1897.

- There is a reality — so subtle that it becomes more real than reality. That's what I'm trying to get down in photography.

- Alfred Stieglitz as cited in: M. Orvell (1989) The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940. p. 220

- Photography, if practiced with high seriousness, is a contest between a photographer and the presumptions of approximate and habitual seeing. The contest can be held anywhere...

- John Szarkowski (1973) Looking at photographs: 100 pictures from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.). p. 192

- My own eyes are no more than scouts on a preliminary search, or the camera's eye may entirely change my idea.

- Edward Weston as cited in: Harold Evans, Edwin Taylor (1978) Pictures on a page: photojournalism and picture editing. p. 75 ; On photojournalism

- The weakness of the attack lies in its lack of discrimination. It is possible that psychic surgery is a hoax, that plants cannot really read our minds, that Kirlian photography (photographing the "life-aura" of living creatures) may depend on some simple electrical phenomenon. But to lump all of these together as if they were all on the same level of improbability shows a certain lack of discernment. The same applies to the list of "hoaxes." Rhine's careful research into extrasensory perception at Duke University is generally conceded to be serious and sincere, even by people who think his test conditions were too loose. The famous fairy photographs are quite probably a hoax, but no one has ever produced an atom of proof either way, and until someone does, no one can be quite as confident as the editors of Time seem to be. And Ted Serios has never at any time been exposed as a fraud — although obviously he might be. We see here a phenomena that we shall encounter again in relation to Geller: that when a scientist or a "rationalist" sets himself up as the defender of reason, he often treats logic with a disrespect that makes one wonder what side he is on.

- Colin Wilson in The Geller Phenomenon, pp. 34-35 (1976)

- A photograph does not stimulate the imaginative mood as good music, poetry, or painting does. In short, photography is too literal. And yet I would call it one of the greatest inventions of the nineteenth century-because of its usefulness to science and its documentary utility in all the arts. As a pictorial feature of magazines it has been vastly overdone and is tiresome...A photograph is the surface of something. Of course an artist is concerned with surface appearances, but only as a means of penetrating to the spirit of the thing. Through his own temperament he reveals the way he is impressed as a beholder of the scene. The artist's emotional reactions subject before him, and his obligation to stress its essentials, are the main factors in a work of art.

- Art Young: His Life and Times (1939)

- …Korolev needed to go full speed ahead with the satellites development, so he stressed the potential military importance of the satellite.

"With the help of the satellite… [it] will be possible to receive important data necessary for future development of science and military technology… it will be possible to conduct photo reconnaissance of the (Earth's) surface…" he wrote in the Aug. 5, 1955, letter to the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.- Anatoly Zak, “The Rocket That Launched Sputnik and Started the Space Race“, Popular Mechanics, (Oct 4, 2017).

External links

edit- World History of Photography From The History of Art.