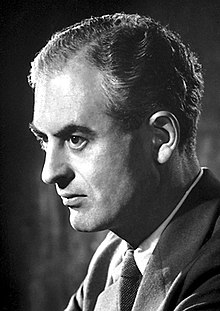

Peter Medawar

English-brazilian biologist (1915–1987)

Sir Peter Medawar (February 28, 1915 – October 2, 1987) was a Brazilian-born English scientist best known for his work on how the immune system rejects or accepts organ transplants. He was co-winner of the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet.

Quotes

edit1950s

edit- The bells which toll for mankind are—most of them, anyway—like the bells of Alpine cattle; they are attached to our own necks, and it must be our fault if they do not make a cheerful and harmonious sound.

- The Future of Man, 1959

1960s

edit- There is no such thing as a Scientific Mind. Scientists are people of very dissimilar temperaments doing different things in very different ways. Among scientists are collectors, classifiers and compulsive tidiers-up; many are detectives by temperament and many are explorers; some are artists and others artisans. There are poet-scientists and philosopher-scientists and even a few mystics. What sort of mind or temperament can all these people be supposed to have in common? Obligative scientists must be very rare, and most people who are in fact scientists could easily have been something else instead.

- "Hypothesis and Imagination" (Times Literary Supplement, 25 Oct 1963)

- The similarity between them is not the taxonomic key to some other, deeper, affinity, and our recognizing its existence marks the end, not the inauguration, of a train of thought.

- In ‘Herbert Spencer and the Law of General Evolution’. Spencer Lecture, Oxford, 1963: reprinted in Medawar, P. B. (1967). The Art of the Soluble. Methuen, London. pp. 37-58.

- Simultaneous discovery is utterly commonplace, and it was only the rarity of scientists, not the inherent improbability of the phenomenon, that made it remarkable in the past. Scientists on the same road may be expected to arrive at the same destination, often not far apart.

- Peter Medawar, "The Act of Creation" (New Statesman, 19 June 1964)

- If politics is the art of the possible, research is surely the art of the soluble. Both are immensely practical-minded affairs.

- Review of Arthur Koestler’s The Act of Creation, in the New Statesman, 19 June 1964

- The human mind treats a new idea the same way the body treats a strange protein; it rejects it.

- In The Art of the Soluble, 1967.

- Scientific discovery is a private event, and the delight that accompanies it, or the despair of finding it illusory, does not travel. One scientist may get great satisfaction from another’s work and admire it deeply; it may give him great intellectual pleasure; but it gives him no sense of participation in the discovery, it does not carry him away, and his appreciation of it does not depend on his being carried away. If it were otherwise the inspirational origin of scientific discovery would never have been in doubt.

- ‘Hypothesis and Imagination’ in The Art of the Soluble, 1967.

- I could quote evidence of the beginnings of a whispering campaign against the virtues of clarity. A writer on structuralism in the Times Literary Supplement has suggested that thoughts which are confused and tortuous by reason of their profundity are most appropriately expressed in prose that is deliberately unclear. What a preposterously silly idea! I am reminded of an air-raid warden in wartime Oxford who, when bright moonlight seemed to be defeating the spirit of the blackout, exhorted us to wear dark glasses. He, however, was being funny on purpose.

- Lecture on 'Science and Literature', 1968.

- Reprinted in Pluto's Republic (Oxford University Press, 1982)

- The purpose of scientific enquiry is not to compile an inventory of factual information, nor to build up a totalitarian world picture of natural Laws in which every event that is not compulsory is forbidden. We should think of it rather as a logically articulated structure of justifiable beliefs about nature.

- Induction and Intuition in Scientific Thought, 1969

Review of Teilhard de Chardin's "The Phenomenon of Man", 1961

edit- Source: "Review of Teilhard de Chardin's The Phenomenon of Man". In: Mind Vol 70 (1961), pp. 99-105

- Yet the greater part of it, I shall show, is nonsense, tricked out with a variety of metaphysical conceits, and its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself.

- In no sense other than an utterly trivial one is reproduction the inverse of chemical disintegration. It is a misunderstanding of genetics to suppose that reproduction is only 'intended' to make facsimiles, for parasexual processes of genetical exchange are to be found in the simplest living things.

- There is much else in the literary idiom of nature-philosophy: nothing-buttery, for example, always part of the minor symptomatology of the bogus.

- The Phenomenon of Man stands square in the tradition of Naturphilosophie, a philosophical indoor pastime of German origin which does not seem even by accident (though there is a great deal of it) to have contributed anything of permanent value to the storehouse of human thought.

- I do not propose to criticize the fatuous argument I have just outlined; here, to expound is to expose.

- How have people come to be taken in by The Phenomenon of Man? We must not underestimate the size of the market for works of this kind, for philosophy-fiction. Just as compulsory primary education created a market catered for by cheap dailies and weeklies, so the spread of secondary and latterly tertiary education has created a large population of people, often with well-developed literary and scholarly tastes, who have been educated far beyond their capacity to undertake analytical thought.

- It is written in an all but totally unintelligible style, and this is construed as prima-facie evidence of profundity.

- French is not a language that lends itself naturally to the opaque and ponderous idiom of nature-philosophy, and Teilhard has according resorted to the use of that tipsy, euphoristic prose-poetry which is one of the more tiresome manifestations of the French spirit.

- It would have been a great disappointment to me if Vibration did not somewhere make itself felt, for all scientistic mystics either vibrate in person or find themselves resonant with cosmic vibrations; but I am happy to say that on page 266 Teilhard will be found to do so.

- In spite of all the obstacles that Teilhard perhaps wisely puts in our way, it is possible to discern a train of thought in The Phenomenon of Man.

The Art of the Soluble, 1967

edit- Source: P. B. Medawar (1967), The art of the soluble, London: Methuen

- It is not envy or malice, as so many people think, but utter despair that has persuaded many educational reformers to recommend the abolition of the English public schools.

- Introduction

- If a person a) is poorly, b) receives treatment intended to make him better, and c) gets better, no power of reasoning known to medical science can convince him that it may not have been the treatment that restored his health.

- p. 14.

Lucky Jim, 1968

edit- Source: "Lucky Jim" (New York Review of Books, 28 March 1968)

- Scientists are entitled to be proud of their accomplishments, and what accomplishments can they call 'theirs' except the things they have done or thought of first? People who criticize scientists for wanting to enjoy the satisfaction of intellectual ownership are confusing possessiveness with pride of possession. Meanness, secretiveness and, sharp practice are as much despised by scientists as by other decent people in the world of ordinary everyday affairs; nor, in my experience, is generosity less common among them, or less highly esteemed.

- It just so happens that during the 1950s, the first great age of molecular biology, the English Schools of Oxford and particularly of Cambridge produced more than a score of graduates of quite outstanding ability —much more brilliant, inventive, articulate and dialectically skilful than most young scientists; right up in the Watson class. But Watson had one towering advantage over all of them: in addition to being extremely clever he had something important to be clever about. This is an advantage which scientists enjoy over most other people engaged in intellectual pursuits, and they enjoy it at all levels of capability. To be a first-rate scientist it is not necessary (and certainly not sufficient) to be extremely clever, anyhow in a pyrotechnic sense. One of the great social revolutions brought about by scientific research has been the democratization of learning. Anyone who combines strong common sense with an ordinary degree of imaginativeness can become a creative scientist, and a happy one besides, in so far as happiness depends upon being able to develop to the limit of one's abilities.

- Watson's childlike vision makes them seem like the creatures of a Wonderland, all at a strange contentious noisy tea-party which made room for him because for people like him, at this particular kind of party, there is always room.

Presidential Address, 1969

edit- Source: Presidential Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Exeter, 3 September 1969

- We cannot point to a single definitive solution of any one of the problems that confront us — political, economic, social or moral, that is, having to do with the conduct of life. We are still beginners, and for that reason may hope to improve. To deride the hope of progress is the ultimate fatuity, the last word in poverty of spirit and meanness of mind. There is no need to be dismayed by the fact that we cannot yet envisage a definitive solution of our problems, a resting-place beyond which we need not try to go.

- Today the world changes so quickly that in growing up we take leave not just of youth but of the world we were young in. I suppose we all realize the degree to which fear and resentment of what is new is really a lament for the memories of our childhood.

- Creosote has a pretty technological smell.

- We shall not read it for its sociological insights, which are non-existent, nor as science fiction, because it has a general air of implausibility; but there is one high poetic fancy in the New Atlantis that stays in the mind after all its fancies and inventions have been forgotten. In the New Atlantis, an island kingdom lying in very distant seas, the only commodity of external trade is — light: Bacon's own special light, the light of understanding.

- On Francis Bacon's New Atlantis

- We wring our hands over the miscarriages of technology and take its benefactions for granted. We are dismayed by air pollution but not proportionately cheered up by, say, the virtual abolition of poliomyelitis.

1970s

edit- It is the great glory as well as the great threat of science that everything which is in principle possible can be done if the intention to do it is sufficiently resolute.

- The Threat and the Glory, 1977

- Only human beings guide their behaviour by a knowledge of what happened before they were born and a preconception of what may happen after they are dead; thus only humans find their way by a light that illuminates more than the patch of ground they stand on.

- (with Jean Medawar) The Life Science, 1977

Advice to a Young Scientist (1979)

edit- Source: Advice to a Young Scientist (1979), p. 13. From chapter 3, "What Shall I Do Research On?"

- It can be said with complete confidence that any scientist of any age who wants to make important discoveries must study important problems. Dull or piffling problems yield dull or piffling answers. It is not enough that a problem should be "interesting" - almost any problem is interesting if it is studied in sufficient depth.

- Source: Advice to a Young Scientist (1979), p. 25, quoting his own article "Unnatural science", New York Review of Books 24 (Feb 3, 1977), pp. 13–18

- To be creative, scientists need libraries and laboratories and the company of other scientists; certainly a quiet and untroubled life is a help. A scientist's work is in no way deepened or made more cogent by privation, anxiety, distress, or emotional harassment. To be sure, the private lives of scientists may be strangely and even comically mixed up, but not in ways that have any special bearing on the nature and quality of their work. If a scientist were to cut off an ear, no one would interpret such an action as evidence of an unhappy torment of creativity; nor will a scientist be excused any bizarrerie, however extravagant, on the grounds that he is a scientist, however brilliant.

- I believe in "intelligence," and I believe also that there are inherited differences in intellectual ability, but I do not believe that intelligence is a simple scalar endowment that can be quanitified by attaching a single figure to it—an I.Q. or the like.

- I once spoke to a human geneticist who declared that the notion of intelligence was quite meaningless, so I tried calling him unintelligent. He was annoyed, and it did not appease him when I went on to ask how he came to attach such a clear meaning to the notion of lack of intelligence. We never spoke again.

- p. 25, footnote to previous quotation.

1980s

edit- Observation is the generative act in scientific discovery. For all its aberrations, the evidence of the senses is essentially to be relied upon—provided we observe nature as a child does, without prejudices and preconceptions, but with that clear and candid vision which adults lose and scientists must strive to regain.

- Medawar, Peter (1982). Pluto's Republic, p. 99. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- A scientist is no more a collector and classifier of facts than a historian is a man who complies and classifies a chronology of the dates of great battles and major discoveries.

- (with Jean Medawar) Aristotle to Zoos: A Philosophical Dictionary of Biology, 1983, p. 27.

- The attempt to discover and promulgate the truth is nevertheless an obligation upon all scientists, one that must be persevered in no matter what the rebuffs—for otherwise what is the point in being a scientist?

- (with Jean Medawar) Aristotle to Zoos: A Philosophical Dictionary of Biology, 1983, p. 196.

- No virus is known to do good: it has been well said that a virus is "a piece of bad news wrapped up in protein."

- (with Jean Medawar) Aristotle to Zoos: A Philosophical Dictionary of Biology, 1983, p. 275.

- I do not believe—indeed, I deem it a comic blunder to believe—that the exercise of reason is sufficient to explain our condition and where necessary to remedy it, but I do believe that the exercise of reason is at all times necessary...

- The Limits of Science. (New York: Harper & Row, 1984) p. 98.

- When asked to make the formal declaration that I did not intend to overthrow the Constitution of the United States, I was fool enough to reply that I had no such purpose, but that were I to do it by mistake I should be inexpressibly contrite.

- P. B. Medawar (1986), Memoir of a thinking radish: an autobiography, Oxford University Press, p. 117.

1990s

edit- Karl Popper’s conception of the scientific process is that is realistic – it gives a pretty fair picture of what goes on in real life laboratories.

- Medawar, Peter B. 1990. The Threat and the Glory: Reflections on Science and Scientists. New York: HarperCollins.[1]

References

edit- ↑ Cited by David Pyke (1991), The Threat and the Glory: Reflections on Science and Scientists, Oxford University Press, p. 100. ISBN 9780192861283, OCLC 1014507545; and also cited by Helge Kragh, “The most philosophically of all the sciences”: Karl Popper and physical cosmology, in Perspectives on science, 21 (2013), 3, pp. 325 - 357, OCLC 907902555 , ISSN 1063-6145 (here cited p. 326).