Patrick Swift

Irish painter (1927-1983)

Patrick Swift (12 August 1927 – 19 July 1983) was an Irish-born painter who worked in Dublin, London and Algarve, Portugal. Founded X magazine (London) and Porches Pottery (Olaria Algarve).

Quotes

edit- I believe when you bring, say, a plant into a room, everything in that room changes in relation to it. This tension — tension is the only word for it — can be painted.

- Time Magazine (20 October 1952).

- Not to paint is the highest ambition of the painter but God who gives the gift requires that it be honoured. It is in the gesture that it lives. There is no escape. Picture-making is ludicrous in the light of the awful times we must endure. It is sufficient to contemplate the nature of composition to see that the picture itself is impossible. Each square inch of Titian contains the whole pointless — between the cradle and the grave. My paintings are merely signs that the activity was engaged in.

- Portuguese Notes (Gandon Editions Biography 1993).

- The Art of painting is itself an intensely personal activity… a picture is a unique and private event in the life of the painter: an object made alone with a man and a blank canvas... A real painting is something which happens to the painter once in a given minute; it is unique in that it will never happen again and in this sense is an impossible object... And it is something which happens in life not in art: a picture which was merely the product of art would not be very interesting and could tell us nothing we were not already aware of. The old saying, “what you don’t know can’t hurt you”, expresses the opposite idea to that which animates the painter before his canvas. It is precisely what he does not know which may destroy him.

- "The Painter in the Press", X magazine, Vol. I, No.4 (October 1960).

- Art on the other hand speaks to us of resignation and rejoicing in reality, and does so through a transformation of our experience of the world into an order wherein all facts become joyous; the more terrible the material the greater the artistic triumph. This has nothing at all to do with "a constant awareness of the problems of our time" or any other vague public concern. It is a transformation that is mysterious, personal and ethical. And the moral effect of art is only interesting when considered in the particular. For it is always the reality of the particular that provides the occasion and the spring of art — it is always "those particular trees/ that caught you in their mysteries" or the experience of some loved object. Not that the matter rests here. It is the transcendent imagination working on this material that releases the mysterious energies which move and speak of deepest existence.

- "The Painter in the Press", X magazine, Vol. I, No.4 (October 1960).

- The development that produces great art is a moral and not an aesthetic development.

- "Italian Report" (December 1955).

- Its life depends on the degree to which it is inhabited by mystery, speaks to us of the unknown.

- "The Painter in the Press", X magazine, Vol. I, No.4 (October 1960).

- All art is probably erotic in its ultimate character, but painting more than anything else is a purely nervous erotic activity.

- "Some Notes on Caravaggio" (Nimbus 1956).

- One who opens his eyes and sees. To be good at seeing. How difficult not to see anything but the visible. And nothing will be left but dust and manure. Attempting the impossible. Approach the mystery.

- Portuguese Notes (Gandon Editions Biography 1993).

- Metaphysics — what metaphysics do those trees have?

- Portuguese Notes (Gandon Editions Biography 1993).

- For to be contemporary is not necessarily to be part of any movement, to be included in the official representations of national and international art. History shows that it may well be the opposite. It may be that it is the odd, the personal, the curious, the simply honest, that at this moment, when everyone looks to the extreme and flamboyant, constitutes the most interesting manifestation of the spirit of art.

- "Official Art and the Modern Painter", X, Vol. I, No. 1 (November 1959).

- Art, if it is successful in the task of questioning reality, if it is good painting and not merely a performance of dexterity, will be an affirmation of God.

- Italian Report (1955).

- The painter celebrates life where he finds it. His morality is the morality of enjoyment, of the continuous development of his own taste without shame or fear. It is a sort of heroism.

- "Mob Morals and the Art of Loving Art", X, Vol. 2, No. 1 (January 1961).

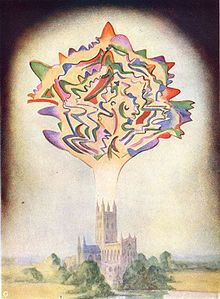

Nano Reid (1950)

edit- "Nano Reid", Envoy: A Review of Literature and Art (March 1950)

- Each work of art is a complete entity existing in its own right and by its own particular logic. It has its own reality and is independent of any particular creed or theory as a justification for its existence. This is not to say that artistic development may be considered as a self-sufficient process unrelated to social reality, because art is always concerned with the deeper and fundamentally human things; and any consideration of art is a consideration of humanity. But it does mean that we cannot apply the principles and logic of the past to a new work of art and hope to understand it. The eternal verities with which the artist is concerned do not change, but our conception of art does, as does our conception of form, and these must be extended if we are to understand fully and basically the meaning of a new work. It is a complex matter, but the elemental principles are always simple. The mass of modern art theory that developed around the fantastic changes of this century's painting can be largely ignored; only one or two fundamental principles are important. Probably most important in the new aesthetics from the painter's point of view was the statement of Degas, seventy years ago, in his unheeded advice to the Impressionists. He spoke then of a "Transformation in which imagination collaborates with memory... It is very well to copy what one sees; it is much better to draw what one has retained in one's memory”…This attitude, and all it implies, underlines the work of practically every painter of importance since 1900. Ultimately, it meant that the day of stage props and models was gone, and that imagination was recognised as the most important quality in an artist.

- In so far as it is concerned with truth that goes beyond appearance and form, art is transcendental. The consciousness of this is often a snare for the painter who is led by a false preoccupation with some literary or intellectual conception of reality into a time-conscious literary form. Nano Reid realised with the instinct of a painter that for her the whole truth existed in the head, the body, the structure of life: it lay there revealed in the form, the line, a timeless and profound reality.

- Nano Reid does not begin a portrait with any ideas about the person she draws. She is concerned with the head, its existence as a structure with certain characteristics. She is so much concerned with this that her portraits are inevitably deep studies of character and personality. The head, the face, the lines and features, contain everything for the painter who understands well enough to put it down.

- New knowledge is only useful in so far as it opens up new vistas for the imagination, and no more so than the old forms which the artist must understand only in order to reject.

The Artist Speaks (1951)

edit- "The Artist Speaks", Envoy: A Review of Literature and Art, Vol. 4, No. 15 (February 1951)

- No real painter ever wants be known through any other medium than his painting.

- Any painter who thinks he has something to say to the people, or anything to contribute to the world of ideas or literature, is treading dangerous ground; the influence of literature on painting is at all times dangerous if not deadly. Painting is a visual art; and the job of the artist must be to create in visual terms the tension experienced. One cannot argue or explain in paint. The aim is not to put in everything that will help, but as little as one can help, so that a picture is in one sense a “sum of destructions”. It is a question of honesty and courage: “One produces only the necessary” — Degas

- Technical criticism in particular is the despair of the artist. No one but an idiot would offer a poet his comments in terms of spondees and trochees; why must the painter daily suffer the indignity? Any picture which makes one conscious first of its technical qualities, good or bad, is not a good picture, whatever else it may be.

- Everything written about art is profoundly unimportant.

- Good painting is not produced by any unintelligent following of inspiration or temperament.

- The only indication of an individual vision is an individual style: "What I seek above all in a picture is a man and not a picture" – Zola

- You may know a good painter by his habit of work: a good painter works constantly.

Italian Report (1955)

edit- Italian Report (December 1955), for the Committee of Cultural Relations, Dept of External Affairs, on a Year spent in Italy in the study of Art & Painting

- For the painter, for whom painting is a vital activity and a way of life — not merely a profession — such attitudes as we find in the histories are deadly. For him the only benefit, at least the deepest and most important benefit, which he can get from the study of the Masters comes from his capacity to see the painting in a thoroughly contemporary way. I mean in the present tense — the tense after all in which it was painted. Not for instance as an early this or a late that, nor as a good example of chiaroscuro or some other aesthetic or technical quality but as an immediately important human statement completely relevant to his life at the moment and convincing for that reason. If a work does not strike the painter in this way all further analysis of it will be futile.

- A more rewarding approach to painting, in my opinion the only valid one, is to regard it as a deeply personal and private activity and to remember that even when the painter works directly for the public — when there is sufficient common ground to allow him to do so — the real merit of the work will depend on the personal vision of the artist and the work will only be truly understood if it is approached by each in the same spirit as the painter painted it. We must be willing to assume the same sort of responsibility and share the dilemma out of which the work was created in order to be able to feel with the artist. Since the deepest and truest dilemma, from which all good art springs, is the human condition we have every right to regard the needs of our own consciousness as the final court in judging the merit of a work of art, we have in fact a moral obligation to do so. This demands the precise honesty from the spectator as was required from the artist in making the painting. It is their common ground, the area within which communication can occur. Art in the end speaks to the secret soul of the individual and of the most secret sorrows. For this reason it is true that the development that produces great art is a moral and not an aesthetic development. .

- It is by deciding what is real for him and portraying it convincingly that the painter serves the true ends of art. The question of “social” reality does not arise on this profoundly personal level. On the other hand the question of personal salvation and our relationship to God does. Art, if it is successful in the task of questioning reality, if it is good painting and not merely a performance of dexterity, will be an affirmation of God.

- Painting is created from within and we must begin from within if we are to understand it.

- I do not know if there are in fact such things as definable social standards of aesthetics that would have any historical or artistic value, but whether there are or not it seems clear to me that for the painter nothing less than complete personal involvement of a moral nature will do.

X magazine (1959-62)

editThe Painter in the Press

- "The Painter in the Press", X, Vol. I, No.4 (October 1960)

- The Art of painting is itself an intensely personal activity. It may be labouring the obvious to say so but it is too little recognised in art journalism now that a picture is a unique and private event in the life of the painter: an object made alone with a man and a blank canvas... A real painting is something which happens to the painter once in a given minute; it is unique in that it will never happen again and in this sense is an impossible object. It is judged by the painter simply as a success or failure without qualification. And it is something which happens in life not in art: a picture which was merely the product of art would not be very interesting and could tell us nothing we were not already aware of. The old saying, “what you don’t know can’t hurt you”, expresses the opposite idea to that which animates the painter before his canvas. It is precisely what he does not know which may destroy him.

- The virtue of hope has only a serious position within the eschatology of true religion. To the man who prays it is the supreme virtue. Art on the other hand speaks to us of resignation and rejoicing in reality, and does so through a transformation of our experience of the world into an order wherein all facts become joyous; the more terrible the material the greater the artistic triumph. This has nothing at all to do with "a constant awareness of the problems of our time" or any other vague public concern. It is a transformation that is mysterious, personal and ethical.* And the moral effect of art is only interesting when considered in the particular. For it is always the reality of the particular that provides the occasion and the spring of art — it is always "those particular trees/ that caught you in their mysteries" or the experience of some loved object. Not that the matter rests here. It is the transcendent imagination working on this material that releases the mysterious energies which move and speak of deepest existence. [*“An ethos is a difficult thing that cannot be formulated and codified; it is one of those creative irrationalities upon which real progress is based. It demands the whole man and not just a differentiated function” — Jung ]

- The idea of objectivity in the evaluation of pictures introduces the concept of rational and scientific assessment. There are some sciences involved in the making and in the study of pictures, but the art itself is finally not a science and will not submit to scientific regimentation because its life depends on the degree to which it is inhabited by mystery, speaks to us of the unknown. It is simply an avoidance of the interesting difficulty to subject the inexplicable to the process of rational explanation. For since the real pleasures of painting and the reality of its meaning exist in the part of its structure which cannot be explained, all suggestions and pretensions at explanation must lead us away from the area of greatest interest. This is to say that such analysis as purports to lay bare the machinery which makes a painting work — makes it a good painting — not only leaves out the most important factor, the element of mystery, but actively denies the reality which is the justification for the art at all.

- For even the painter himself cannot be fully aware of the way in which the picture gets made: there is a wide area of the unpredictable in the act of pushing paint about in the definition of an image.

- There are ambiguities in the art of painting but they are the ambiguities of a fine precision: the discovered fact of the image containing at the same time the reverberations of the unknown, the truly mysterious… I would take this further and add that painting is itself precise in its ideas. In the sense that the image is the idea in its purist form.* [*“The image is a principal of our knowledge. It is that from which our intellectual activity begins, not as a passing stimulus but as an enduring foundation” — St. Thomas Aquinas, Opus XVI]

- The interesting thing is what happens in the specific picture: its precision in terms of the sensations it produces — the illusion it creates and the effect of this illusion on the psychology opposed to it. General philosophical and technical information however interesting in itself is secondary to this reality.

- For the notion of progress in the arts, (either spiritually or artistically) has been discredited by many respectable intellects (Kierkegaard and Baudelaire above all, both of whom encountered the idea when it first reared itself in its present form in Europe).

Official Art and the Modern Painter

- "Official Art and the Modern Painter", X magazine, Vol. I, No. 1 (November 1959)

- A situation has occurred wherein a premium is put on any work qualifying for the term "progressive"… The idea of progress in the arts; the notion that we move forward from one good thing to another in a simple progression and in a single direction... Baudelaire dealt so profoundly with this... But this can be said: if there were such a thing as a direct and simple progression from the work of one generation to the next the historical difficulty of the Progressive Artist could not exist... the popular notion of the Progressive and the New Art may not after all be the last word on a complex subject. That there may be, even to-day... such a thing as the absolutely modern. That as before it may be something unexpected, and not completely accounted for in the arrangements for encouraging the arts... For to be contemporary is not necessarily to be part of any movement, to be included in the official representations of national and international art. History shows that it may well be the opposite. It may be that it is the odd, the personal, the curious, the simply honest, that at this moment, when everyone looks to the extreme and flamboyant, constitutes the most interesting manifestation of the spirit of art... It may be necessary to be absolutely modern.

- It is noticeable that rejection and selection no longer operate in terms of merely quality but on kind. This is exactly the situation confronting the Impressionists who attempted to show their works in the salon of 1865.

Mob Morals and the Art of Loving Art

- "Mob Morals and the Art of Loving Art", X, Vol. 2, No. 1 (January 1961)

- It is not necessary to subscribe to the tiresome conception of the artist as rampaging Bohemian to understand that the activity of painting is socially useless, or at best occupies a dubious position...In the remote purity of his solitariness, where the work of art is made, the artist is supremely the anti-social creature.

- In the end each man experiences only himself. To refer to your neighbour or twenty million of them for your touchstone of reality is a logical nonsense in the life of the individual person. When one reflects on the personality of Lautrec in these pictures, brave, unconcerned, scornful, and violent, it becomes a monstrosity of sophism to consider his size or shape as relevant factors.The painter celebrates life where he finds it. His morality is the morality of enjoyment, of the continuous development of his own taste without shame or fear. It is a sort of heroism.

- There is a sense, and a very exciting sense, in which art is moral. When Stendhal says a good picture is nothing but a construction in ethics, one recognises a truth about art which opens up vistas that are at the same time liberating and terrifying. The ethics of art are terrifying because real art by increasing our knowledge of ourselves increases in exactly the same proportion the ethical commitment.

- The techniques for making art thus morally acceptable, of drawing its fangs, are endless; and each generation finds its own. Just now the democratic machinery for rendering art safe is so efficient that it seems that the system can absorb anything. It would be exciting to think that somewhere in Europe there was a man making art which was so violent and true that the system could not take it.

Some Notes on Caravaggio (1956)

edit- "Some Notes on Caravaggio", Nimbus, Vol. III, No. 4 (Winter 1956)

- Caravaggio speaks to us out of a consciousness that is brooding and obsessive, and affects us in a way that is not simply artistic. By this I mean that he comes close to presenting us with a sensation of amorphous and desperate desire unredeemed by an authoritative vision. It can be felt in the apprehensive boredom of the unsuccessful pictures and in the oppressive intensity of the best. If this sensation were deep enough it might have destructive effects, since we all live within that margin of order which we succeed in imposing on life, i.e., on the unfulfilled longings of the heart, and his work might then be truly diabolic. His genius operates in that world of antithesis where the conflict between ideal and reality rages, and the moral victory, i.e., the ultimate affirmation of the goodness of life, is always so tenuously won that we feel the dread of chaos intensely- even when he is completely successful. If there could be such a contradictory phenomenon as the uninnocent artist he might be it. He indicates the sort of sensations we might expect from such a monster. But since he is wholly innocent beneath the apparent evidence of corruption he ends by moving us in a profound and religious way.

- His work is full of the signs of those two cardinal sins from which (as Kafka pointed out) all the others spring: impatience and laziness. The work of every artist is conditioned by the way in which he resists or yields to these temptations.

- But of course these pictures are not shocking; good painting never is.

- They verge on the realm of the confession- hovering on that vital line between the simply revelatory and consequently vulgar, and the honest statement that is moral and consequently dignified.

- Perhaps this is the great weakness of all criticism, that it tends to take facts derived from the examination of unimportant works and applies them in making a judgement about a man whose whole importance rests in the successful work, where these facts do not exist.

- All art is probably erotic in its ultimate character, but painting more than anything else is a purely nervous erotic activity... The eroticism of Caravaggio is special because it exists in that area between the simple sensual appreciation of the object which produces the desire to possess it, and the passionate but detached concern of the Observer, which also seeks to possess but to possess through understanding.

- Its purpose is moral, that is, the evaluation of experience; in the deepest sense, the development of taste.

Notebooks

edit- Italian Notebook (1954/55), Gandon Editions Biography 1993

- I think that I probably have a real talent for painting trees if I developed it assiduously. I want to give them great density and depth pile heaps of detail into them and yet keep the sense of presence which is the whole point.

- Portuguese Notebooks, Gandon Editions Biography 1993

- Not to paint is the highest ambition of the painter but God who gives the gift requires that it be honoured. It is in the gesture that it lives. There is no escape. Picture-making is ludicrous in the light of the awful times we must endure. It is sufficient to contemplate the nature of composition to see that the picture itself is impossible. Each square inch of Titian contains the whole pointless — between the cradle and the grave. My paintings are merely signs that the activity was engaged in.

- To paint even a bottle is dramatic. A leaf will do.

- To know what it is to look at things, life as a prayer, a mass, a celebration.

- One who opens his eyes and sees. To be good at seeing. How difficult not to see anything but the visible. And nothing will be left but dust and manure. Attempting the impossible. Approach the mystery.

- Metaphysics — what metaphysics do those trees have?

- What trace of the creature subsists in the work. It is a way of staying alone, passing the time subjected to the object — silent, still. Walk with humility in the landscape. To be some natural thing — an ancient tree — no thinking — not to think is central to the activity.

- There is the modern phenomenon of the artist declaring all is void, nothing is possible, and soon is making his fortune out of despair and emptiness. I am too romantic to accept the dishonesty inherent in such a role, or perhaps it is my religious education. Such a position cannot be a religious position. (I) do not accept that the artist should not engage in other activities though when he does he must accept a different responsibility.

- Life is more important than art — quantity is only important in that the amount of activity is greater not the number of works.

- Obey God by living spontaneously.