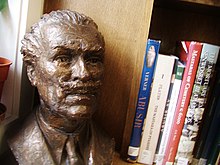

Mortimer Wheeler

British archaeologist (1890-1976)

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler FRS FBA FSA (10 September 1890 – 22 July 1976) was a British archaeologist and officer in the British Army. Over the course of his career, he served as Director of both the National Museum of Wales and London Museum, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, and the founder and Honorary Director of the Institute of Archaeology in London, in addition to writing twenty-four books on archaeological subjects.

Quotes

edit- ‘For a civilization so widely distributed as that of the Indus no uniform ending need be postulated.’

- quoted from Danino, M. (2020). Climate, Environment, and the Harappan Civilization. R. Chakrabarti, Critical Themes in Environmental History of India, 333-377.

- The anthropologists who have recently described the skeletons from Harappa remark that there, as at Lothal, the population would appear, on the available evidence, to have remained more or less stable to the present day.

- Sir M. Wheeler: The Indus Civilization, Cambridge University Press 1968, p.72, quoted in K.D. Sethna: The Problem of Aryan Origins, Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi 1992 (1980), p.20.quoted in Elst, Koenraad (1999). Update on the Aryan invasion debate New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Archaeology is not a science, it’s a vendetta.

- Attributed. (Sir Mortimer Wheeler, as quoted, without citation, in [1])

- The Aryan invasion of the Land of Seven Rivers, the Punjab and its envi- rons, constantly assumes the form of an onslaught upon the walled cities of the aborigines. For these cities the term used in the ¸igveda is pur, mean- ing a “rampart,” “fort” or “stronghold.” . . . Indra, the Aryan War god, is puraydara, “fort-destroyer.” He shatters “ninety forts” for his Aryan protégé Divodasa. [. . .] Where are – or were – these citadels? It has in the past been supposed that they were mythical, or were “merely places of refuge against attack, ramparts of hardened earth with palisades and a ditch.” The recent exca- vation of Harappa may be thought to have changed the picture. Here we have a highly evolved civilization of essentially non-Aryan type, now known to have employed massive fortifications, and known also to have dominated the river-system of north-western India at a time not distant from the likely period of the earlier Aryan invasions of that region. What destroyed this firmly settled civilization? Climatic, economic, political deterioration may have weakened it, but its ultimate extinction is more likely to have been completed by deliberate and large-scale destruction. It may be no mere chance that at a late period of Mohenjo-daro men, women and children appear to have been massacred there. On circumstantial evidence, Indra stands accused.

- (Wheeler 1947: 82) in Bryant, E. F., & Patton, L. L. (2005). The Indo-Aryan controversy : evidence and inference in Indian history. Routledge page 52

- Wheeler (1968, 3rd edition) proposed the following: It is, simply, this. Sometime during the second millennium B.C. – the middle of the millennium has been suggested, without serious support – Aryan-speaking peoples invaded the Land of Seven Rivers, the Punjab and its neighboring region. It has long been accepted that the tradition of this invasion is reflected in the older hymns of the Rigveda, the composi- tion of which is attributed to the second half of the millennium. In the Rigveda, the invasion constantly assumes the form of an onslaught upon walled cities of the aborigines. For these cities, the term used is pur, meaning a “rampart,” “fort,” “stronghold.” One is called “broad” ( prithvi) and “wide” (urvi). Sometimes strongholds are referred to metaphorically as “of metal” (dyasi). “Autumnal” (saradi) forts are also named: “this may refer to the forts in that season being occupied against the Aryan attacks or against inundations caused by overflowing rivers.” Forts “with a hundred walls” (satabhuji) are mentioned. The citadel may be of stone (afmanmayi): alternatively, the use of mud-bricks is perhaps alluded to by the epithet ama (raw, unbaked); Indra, the Aryan war-god is purandara, “fort-destroyer.” He shatters “ninety forts” for his Aryan protégé, Divodasa. The same forts are doubtless referred to where in other hymns he demolishes variously ninety-nine and a hundred “ancient castles” of the aboriginal leader Sambara. In brief, he renders “forts as age consumes garment.” If we reject the identification of the fortified citadels of the Harappans with those which the Aryans destroyed, we have to assume that, in the short interval which can, at the most, have intervened between the end of the Indus civilization and the first Aryan invasions, an unidentified but formidable civilization arose in the same region and presented an extensive fortified front to the invaders. It seems better, as the evidence stands, to accept the identification and to suppose that the Harappans of the Indus valley in their decadence, in or about the seventeenth century BC, fell before the advancing Aryans in such fashion as the Vedic hymns proclaim: Aryans who nevertheless, like other rude conquerors of a later date, were not too proud to learn a little from the conquered . . . (1968: 131–2)

- quoted in Jim Shaffer. South Asian archaeology and the myth of Indo-Aryan invasions in : Bryant, E. F., & Patton, L. L. (2005). The Indo-Aryan controversy : evidence and inference in Indian history. Routledge

- The city, so far from being an unarmed sanctuary of peace, was dominated by the towers and battlements of a lofty man‐made acropolis of defiantly feudal aspect. A few minutes’ observation had radically changed the social character of the Indus civilization and put it at last into an acceptable secular focus. (Wheeler, 1955: 192)

- quoted in Michel Danino, in : Walimbe, S. R., & Schug, G. R. (2016). A companion to South Asia in the past. chapter 13. Aryans and the Indus Civilization: Archaeological, Skeletal, and Molecular Evidence

- Wheeler REM. 1955. Still digging: interleaves from an antiquary notebook. London: Michael Joseph.

- One terracotta, from a late level of Mohenjo-daro, seems to represent a horse, reminding us that the jaw-bone of a horse is also recorded from the site, and that the horse was known at a considerably earlier period in northern Baluchistan”

- R. E. M. Wheeler, The Indus Civilization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 3rd edition, 1968, p. 92 (in Lal, B. B. (2005). Can the Vedic people be identified archaeologically?–An approach. IT, 31, 173-194.)

About

edit- Since India’s and Pakistan’s independence, South Asian archaeology was significantly influenced by Sir Mortimer Wheeler (born 1890, died 1976) and, to a lesser degree, by the late Stuart Piggott. Wheeler secured a reputation as one of the most prominent archaeologists in the English speaking world.... If Jones’ had his “philologer paragraph,” Wheeler had his “Aryan paragraphs” which directed archaeological, historical, linguistic, and biological interpretations within South Asian studies for over a half century.

- Jim Shaffer. South Asian archaeology and the myth of Indo-Aryan invasions in : Bryant, E. F., & Patton, L. L. (2005). The Indo-Aryan controversy : evidence and inference in Indian history. Routledge

- Given the charge of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1944, when he was a brigadier in the British army fighting in North Africa, he revived the ASI and institutionalized a more rigorous stratigraphic method designed to record a site’s evolution period after period. Irascible but magnanimous, theatrical but hard-working, Wheeler energetically put his stamp on Indian archaeology. But having received his archaeological training in the context of the Roman Empire, he transferred its terminology wholesale to the Harappan cities, which thus became peppered with ‘citadels’, ‘granaries’, ‘colleges’, ‘defence walls’, etc., when no one, in reality, had a clue to the precise purpose of the massive structures that had emerged from the thick layers of accumulated mud.

- Danino, M. (2010). The lost river : on the trail of the Sarasvatī. Penguin Books India.

- One important legacy of Wheeler's influence is an a priori acceptance by scholars of the use of migration and stimulus diffusion to describe all major South Asian discontinuities - beginning with the invention of agriculture and ending with the arrival of the British. Alternative explanations of cultural change are not considered. Wheeler's interpretations promoted an encapsulation of South Asian culture history into a series of chronologically and culturally distinct units focused on northern areas. It the became difficult to perceive or reconstruct a cultural account incorporating an integrated sub-continent. Recent archaeological data suggests fundamental interpretive changes are now warranted.

- Migration, philology and South Asian archaeology by Jim G. Schaffer & Diane A. Lichtenstein