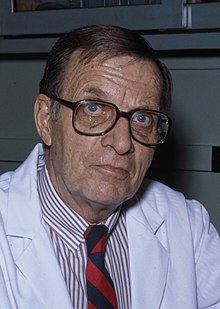

Lewis Thomas

American physician, poet and educator (1913-1993)

Lewis Thomas (25 November 1913 - 3 December 1993) was a physician, author, administrator, educator, policy advisor and researcher. He served as a Dean of Yale Medical School, Dean of the New York University School of Medicine and President of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Institute.

Quotes

edit- It is not a simple life to be a single cell, although I have no right to say so, having been a single cell so long ago myself that I have no memory at all of that stage in my life.

- A Long Line of Cells : Collected Essays (1990), p. 244

- I must mend the ways of my mind. This is a very big place, and I do not know how it works. I am a member of a fragile species, still new to the earth, the youngest creatures of any scale, here only a few moments as evolutionary time is measured, a juvenile species, a child of a species. We are only tentatively set in place, error prone, at risk of fumbling, in real danger at the moment of leaving behind only a thin layer of our fossils, radioactive at that.

- The Fragile Species (1992)

Aspects of Biomedical Science Policy (1972)

edit- The New England Journal of Medicine (12 October 1972)

- The great secret, known to internists and learned early in marriage by internist’s wives, but still hidden from the general public, is that most things get better by themselves. Most things, in fact, are better by morning. Obviously, it is a great time-saver and money-saver for the physician’s family that anxiety about disease is not handled as though it were the disease itself; there is perhaps greater willingness to accept anxiety as a natural, often transient, phenomenon. And certainly there is much less ambition to deploy the full technology of medicine as a corrective for the human condition.

- p. 3

- It is conceivable that we might be able to provide good medical care for everyone needing it, in a new system designed to assure equity, provided we can restrain ourselves, or our computers, from designing a system in which all 200 million of us are assumed to be in constant peril of failed health every day of our lives. In the same sense that our judicial system presumes us to be innocent until proven guilty, a medical care system may work best if it starts with the presumption that most people are healthy. Left to themselves, computers may try to do it in the opposite way, taking it as given that some sort of direct, continual, professional intervention is required all the time, in order to maintain the health of each citizen, and we will end up spending all our money on nothing but this.

- p. 4

The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher (1974)

edit- The need to make music, and to listen to it, is universally expressed by human beings. I cannot imagine, even in our most primitive times, the emergence of talented painters to make cave paintings without there having been, near at hand, equally creative people making song. It is, like speech, a dominant aspect of human biology.

- "The Music of This Sphere"

- It is when physicians are bogged down by their incomplete technologies, by the innumerable things they are obliged to do in medicine when they lack a clear understanding of disease mechanisms, that the deficiencies of the health-care system are most conspicuous. If I were a policy-maker, interested in saving money for health care over the long haul, I would regard it as an act of high prudence to give high priority to a lot more basic research in biologic science.

- "The Technology of Medicine"

- Perhaps the safest thing to do at the outset, if technology permits, is to send music. This language may be the best we have for explaining what we are like to others in space, with least ambiguity. I would vote for Bach, all of Bach, streamed out into space, over and over again. We would be bragging of course, but it is surely excusable to put the best possible face on at the beginning of such an acquaintance. We can tell the harder truths later.

- "Vibes"

- It is nice to think that there are so many unsolved puzzles ahead for biology, although I wonder whether we will ever find enough graduate students.

- "Ceti"

- We hanker to go on, even in the face of plain evidence that long, long lives are not necessarily pleasurable in the kind of society we have arranged thus far. We will be lucky if we can postpone the search for new technologies for a while, until we have discovered some satisfactory things to do with the extra time.

- "The Long Habit"

- Ants are more like the parts of an animal than entities on their own. They are mobile cells, circulating through a dense connective tissue of other ants in a matrix of twigs. The circuits are so intimately interwoven that the anthill meets all the essential criteria of an organism.

- "Antaeus in Manhattan"

- If we have learned anything at all in this century, it is that all new technologies will be put to use, sooner or later, for better or worse, as it is in our nature to do.

- "Autonomy"

- I can think of a few microorganisms, possibly the tubercle bacillus, the syphilis spirochete, the malarial parasite, and a few others, that have a selective advantage in their ability to infect human beings, but there is nothing to be gained, in an evolutionary sense, by the capacity to cause illness or death. Pathogenicity may be something of a disadvantage for most microbes, carrying lethal risks far more frightening to them than to us. The man who catches a meningococcus is in considerably less danger for his life, even without chemotherapy, than meningococci with the bad luck to catch a man.

- "Germs"

- Cells are required to stick precisely to the point. Any ambiguity, any tendency to wander from the matter at hand, will introduce grave hazards for the cells, and even more for the host in which they live. Minor inaccuracies may cause reactions in which neighboring cells are recognized as foreign, and done in. There is a theory that the process of aging may be due to the cumulative effect of imprecision, a gradual degrading of information. It is not a system that allows for deviating.

- "Information"

- The future is too interesting and dangerous to be entrusted to any predictable, reliable agency. We need all the fallibility we can get. Most of all, we need to preserve the absolute unpredictability and total improbability of our connected minds. That way we can keep open all the options, as we have in the past.

- "Computers"

- Statistically the probability of any one of us being here is so small that you would think the mere fact of existence would keep us all in a contented dazzlement of surprise. We are alive against the stupendous odds of genetics, infinitely outnumbered by all the alternates who might, except for luck, be in our places.

- "On Probability and Possibility"

The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher (1979)

edit- Science gets most of its information by the process of reductionism, exploring the details, then the details of the details, until all the smallest bits of the structure, or the smallest parts of the mechanism, are laid out for counting and scrutiny. Only when this is done can the investigation be extended to encompass the whole organism or the entire system. So we say.

Sometimes it seems that we take a loss, working this way.- "The Tucson Zoo", p. 8

- We are endowed with genes which code out our reaction to beavers and otters, maybe our reaction to each other as well. We are stamped with stereotyped, unalterable patterns of response, ready to be released. And the behavior released in us, by such confrontations, is, essentially, a surprised affection. It is compulsory behavior and we can avoid it only by straining with the full power of our conscious minds, making up conscious excuses all the way. Left to ourselves, mechanistic and autonomic, we hanker for friends.

- "The Tucson Zoo", p. 9

- Everyone says, stay away from ants. They have no lessons for us; they are crazy little instruments, inhuman, incapable of controlling themselves, lacking manners, lacking souls. When they are massed together, all touching, exchanging bits of information held in their jaws like memoranda, they become a single animal. Look out for that. It is a debasement, a loss of individuality, a violation of human nature, an unnatural act.

Sometimes people argue this point of view seriously and with deep thought. Be individuals, solitary and selfish, is the message. Altruism, a jargon word for what used to be called love, is worse than weakness, it is sin, a violation of nature. Be separate. Do not be a social animal. But this is a hard argument to make convincingly when you have to depend on language to make it. You have to print out leaflets or publish books and get them bought and sent around, you have to turn up on television and catch the attention of millions of other human beings all at once, and then you have to say to all of them, all at once, all collected and paying attention: be solitary; do not depend on each other. You can’t do this and keep a straight face.- "The Tucson Zoo", p. 10

- Maybe altruism is our most primitive attribute out of reach, beyond our control. Or perhaps it is immediately at hand, waiting to be released, disguised now, in our kind of civilization as affection or friendship or attachment. I can’t see why it should be unreasonable for all human beings to have strands of DNA coiled up in chromosomes, coding out instincts for usefulness and helpfulness. Usefulness may turn out to be the hardest test of fitness for survival, more important than aggression, more effective, in the long run, than grabbiness.

- "The Tucson Zoo", p. 10

- Maybe there is a single spot, just one, where living organisms are holed up. Maybe so, but if so this would be the strangest thing of all, absolutely incomprehensible. For we are not familiar with this kind of living. We do not have solitary, isolated creatures. It is beyond our imagination to conceive of a single form of life that exists alone and independent, unattached to other forms.

- "The Youngest and Brightest Thing Around", p. 13

- Everything here is alive thanks to the living of everything else.

- "The Youngest and Brightest Thing Around", p. 14

- As a people we have become obsessed with Health. There is something fundamentally, radically unhealthy about all this. We do not seem to be seeking more exuberance in living as much as staving off failure, putting off dying. We have lost all confidence in the human body.

- "The Health-Care System", p. 47

- The cloning of humans is on most of the lists of things to worry about from Science, along with behavior control, genetic engineering, transplanted heads, computer poetry and the unrestrained growth of plastic flowers.

- "On Cloning a Human Being", p. 52

- I agree that you might clone some people who would look amazingly like their parental cell donors, but the odds are that they’d be almost as different as you or me, and certainly more different than any of today’s identical twins.

- "On Cloning a Human Being", p. 53

The Youngest Science: Notes of a Medicine Watcher (1983)

edit- I have always had a bad memory, as far back as I can remember.

- "Amity Street", p. 1

- It is my belief, based partly on personal experience but partly also arrived at by looking around at others, that childhood lasts considerably longer in the males of our species than in the females.

- "Scabies, Scrapie", p. 236