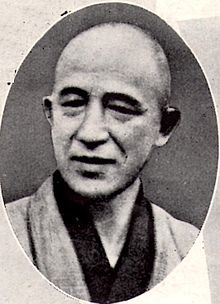

Keiji Nishitani

Japanese philosopher (1900–1990)

Keiji Nishitani (February 27, 1900 – November 24, 1990) was a Japanese philosopher of the Kyoto School and a disciple of Kitaro Nishida.

Quotes

edit- In the religiosity of Zen Buddhism, demythologization of the mythical and existentialization of the scientific belong to one and the same process.

- as cited in Zen Skin, Zen Marrow (Oxford: 2008), p. 134

The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism (1990)

edit- On the one hand, nihilism is a problem that transcends time and space and is rooted in the essence of human being, an existential problem in which the being of the self is revealed to the self itself as something groundless. On the other hand, it is a historical and social phenomenon, an object of the study of history. The phenomenon of nihilism shows that our historical life has lost its ground as objective spirit, that the value system which supports this life has broken down, and that the entirety of social and historical life has loosened itself from its foundations. Nihilism is a sign of the collapse of the social order externally and of spiritual decay internally - and as such signifies a time of great upheaval. Viewed in this way, one might say that it is a general phenomenon that occurs from time to time in the course of history.

- p. 3

- Previous ideals and values undermine themselves and collapse into nothing precisely as a result of the effort to make them consummate and exhaustive.

- p. 104

- Through the sincerity cultivated by Christian morality the values and ideals established by that morality itself are revealed as fictions.

- Summarizing Nietzsche’s views, p. 109

- In principle, when we distinguish being from beings, we transcend the realm of things that are. It is not that we go to some other world beyond the world we know, or enter into some different realm of beings. Such notions constitute, for Heidegger, a vulgar form of metaphysics with which true philosophy (metaphysics as science) has nothing in common. Philosophy does not go beyond beings ontically to other beings that dwell beyond or behind. It transcends beings ontologically in the direction of being.

- p. 163

- Ironically, it was not in his nihilistic view of Buddhism but in such ideas as amor fati and the Dionysian as the overcoming of nihilism that Nietzsche came closest to Buddhism, and especially to Mahāyāna.

- p. 180

- From the perspective of Buddhism, Sartre’s notion of Existence, according to which one must create oneself continually in order to maintain oneself within nothing, remains a standpoint of attachment to the self – indeed, the most profound form of this attachment – and as such is caught in the self-contradiction this implies.

- p. 187

- A crisis is taking place in the contemporary world in a variety of forms, cutting across the realms of culture, ethics, politics, and so forth. At the ground of these problems is the fact that the essence of being human has turned into a question mark for humanity itself.

- p. 188

- In the locus of emptiness, beyond the human standpoint, a world of "dependent origination" is opened up in which everything is related to everything else. Seen in this light, there is nothing in the world that arises from "self-power" and yet all "self-powered" workings arise from the world.

- p. 190

Religion and Nothingness (1983)

edit- "Nothingness" is generally forced into a relationship with "being" and made to serve as its negation, leading to its conception as something that "is" nothingness because it "is not" being. This seems to be especially evident in Western thought, even in the "nihility" of nihilism. But insofar as one stops here, nothingness remains a mere concept, a nothingness only in thought. Absolute nothingness, wherein even that "is" is negated, is not possible as a nothingness that is thought but only as a nothingness that is lived. It was remarked above that behind person there is nothing at all, that is, that "nothing at all" is what stands behind person. But this assertion does not come about as a conceptual conversion, but only as an existential conversion away from the mode of being of person-centered person. Granted what we have said about the person-centered self-prehension of person as being intertwined with the very essence and realization of the personal, the negation of person-centeredness must amount to an existential self-negation of man as person. The shift of man as person from person-centered self-prehension to self-revelation as the manifestation of absolute nothingness - of which I shall speak next - requires an existential conversion, a change of heart within man himself.

- p. 70

- People give names to persons and things, and then suppose that if they know the names, they know that which the names refer to.

- p. 101

- All things that are in the world are linked together, one way or the other. Not a single thing comes into being without some relationship to every other thing. Scientific intellect thinks here in terms of natural laws of necessary causality; mythico-poetic imagination perceives an organic, living connection; philosophic reason contemplates an absolute One. But on a more essential level, a system of circuminsession has to be seen here, according to which, on the field of Śūnyatā, all things are in a process of becoming master and servant to one another. In this system, each thing is itself in not being itself, and is not itself in being itself. Its being is illusion in its truth and truth in its illusion. This may sound strange the first time one hears it, but in fact it enables us for the first time to conceive of a force by virtue of which all things are gathered together and brought into relationship with one another, a force which, since ancient times, has gone by the name of "nature" (physis).

- p. 149