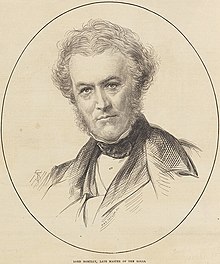

John Romilly, 1st Baron Romilly

English Whig politician and judge (1802-1874)

John Romilly, 1st Baron Romilly (20 January 1802 – 23 December 1874), known as Sir John Romilly between 1848 and 1866, was an English Whig politician and judge. He served in Lord John Russell's first administration as Solicitor-General from 1848 to 1850 and as Attorney-General from 1850 and 1851. The latter year he was appointed Master of the Rolls, a post he held until 1873. Knighted in 1848, he was ennobled as Baron Romilly in 1866.

Quotes

edit- Courts of equity have always considered it of the greatest possible importance that parties should not sleep on their rights.

- Browne v. Cross (1852), 14 Beav. 113.

- A master should be paid liberally, in order to secure a person properly qualified.

- Att.-Gen. v. Warden, &c. of Louth School (1852), 14 Beav. 206.

- The duty of relieving his fellow creature in distress is imposed on the Christian irrespective of religious doctrines and tenets, and notwithstanding that the object of charity may worship God in an erroneous manner, but in that which he believes to be most acceptable to his Creator.

- Att.-Gen. v. Calvert (1857), 23 Beav. 258.

- If a client be present in Court, and stand by and see his solicitor enter into terms of an agreement, and makes no objection whatever to it, he is not at liberty afterwards to repudiate it.

- Swinfen v. Swinfen (1857), 24 Beav. 559.

- The decisions of the House of Lords are binding on me and upon all the Courts except itself.

- Att.-Gen. v. The Dean and Canons of Windsor (1858), 24 Beav. 715.

- The plaintiff cannot dive into the secret recesses of his (the defendant's) heart.

- In Re Ward (1862), 31 Beav. 7.

- If a man who makes to another person, upon a solemn occasion, an assertion, upon which that person acts, he lies under an obligation to make good his assertion.

- In Re Ward (1862), 31 Beav. 7.

- The Court exercises its jurisdiction for the enforcement of the truth, and makes a man's acts square with his words, by compelling him to perform what he has undertaken.

- Laver v. Fielder (1862), 32 Beav. 13.

- There is no magic in words.

- Lord v. Jeffkins (1865), 35 Beav. 16.

- The public can have no rights springing from injustice to others.

- Walker v. Ware, Hadham, &c. Rail. Co. (1866), 12 Jur. (N. S.) 18.

- Clubs are very peculiar institutions. They are societies of gentlemen who meet principally for social purposes, superadded to which there are often certain other purposes, sometimes of a literary nature, sometimes to promote political objects, as in the Conservative or the Reform Club. But the principal objects for which they are designed are social, the others are only secondary. It is, therefore, necessary that there should be a good understanding between all the members, and that nothing should occur that is likely to disturb the good feeling that ought to subsist between them.

- Hopkinson v. Marquis of Exeter (1867), L. R. 5 Eq. Ca. 67.

- It is essential, when persons in trade come into this Court, that they should remember that the administration of equity is founded on perfect truth, and that if persons attempt to mislead the public by stating that which is not true, this Court will restrain them upon a clear case being made out against them.

- Cocks v. Chandler (1871), L. R. 11 Eq. Ca. 449.

- There is no point on which a greater amount of decision is to be found in Courts of law and equity than as to what is reasonable; for instance, reasonable time, reasonable notice, and the like. It is impossible a priori to state what is reasonable in such cases. You must have the particular facts of each case established before you can ascertain what is meant by reasonable time, notice, and the like.

- Labouchere v. Dawson (1872), L. R. 13 Eq. Ca. 325.