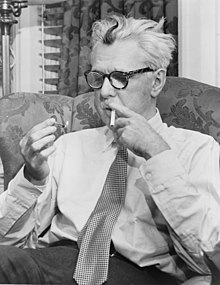

James Thurber

American cartoonist, author, journalist, playwright (1894–1961)

James Grover Thurber (8 December 1894 – 2 November 1961) was an American humorist and cartoonist.

Quotes

editCartoon captions

edit- All right, have it your way — you heard a seal bark!

- Cartoon caption, The New Yorker (30 January 1932); "Women and Men", The Seal in the Bedroom and Other Predicaments (1932); also used in "The Lady on the Bookcase", Alarms and Diversions (1957).

- Le coeur a ses raisons, Mrs. Bence, que la raison ne connait pas.

- Cartoon caption, The New Yorker (27 July 1935)

- Borrowing from Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 1670 (published posthumously): "Le coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît point" (Translation: The heart has its reasons, which reason does not know.)

- Well, if I called the wrong number, why did you answer the phone?

- Cartoon caption, The New Yorker (5 June 1937); "Word Dance--Part One", A Thurber Carnival (1960)

- I love the idea of there being two sexes, don't you?

- Cartoon caption, The New Yorker (22 April 1939); "A Miscellany", Alarms and Diversions (1957)

- He knows all about art, but he doesn't know what he likes.

- Cartoon caption, The New Yorker (4 November 1939). Parody of "I don't know much about art, but I know what I like."

- Variant: He knew all about art, but he didn't know what you like.

- "Word Dance — Part One", A Thurber Carnival (1960)

- It's a naïve domestic Burgundy without any breeding, but I think you'll be amused by its presumption.

- Cartoon caption (1944), in which a dinner host is speaking to his guests about the wine, reproduced in The Thurber Carnival (1945).

Fables for Our Time and Further Fables for Our Time

edit- There is no safety in numbers, or in anything else.

- "The Fairly Intelligent Fly", The New Yorker (4 February 1939), a tale of a fly who avoided getting caught in an empty spider web, but then disregarding a warning by a bee, settled down among other flies he believed to be "dancing", and "became stuck to the flypaper with all the other flies."; Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940); Quote Investigator notes that this statement was referred to as "Thurber’s Law", in 1,001 Logical Laws (1979)

- A burden in the bush is worth two on your hands.

- "The Hunter and the Elephant", The New Yorker (18 February 1939)

- It is better to ask some of the questions than to know all the answers.

- "The Scotty Who Knew Too Much", The New Yorker (18 February 1939)

- Early to rise and early to bed makes a male healthy and wealthy and dead.

- "The Shrike and the Chipmunks", The New Yorker (18 February 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940). Because it is derived from Benjamin Franklin's famous saying this is often misquoted as: Early to rise and early to bed makes a man healthy, wealthy, and dead.

- You might as well fall flat on your face as lean over too far backward.

- "The Bear Who Let It Alone", The New Yorker (29 April 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940)

- You can fool too many of the people too much of the time.

- "The Owl who was God", The New Yorker (29 April 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940). Parody of "You can fool all the people some of the time and some of the people all of the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time."

- Once upon a sunny morning a man who sat in a breakfast nook looked up from his scrambled eggs to see a white unicorn with a golden horn quietly cropping the roses in the garden. The man went up to the bedroom where his wife was still asleep and woke her. "There's a unicorn in the garden," he said. "Eating roses." She opened one unfriendly eye and looked at him. "The unicorn is a mythical beast," she said, and turned her back on him. The man walked slowly downstairs and out into the garden. The unicorn was still there; he was now browsing among the tulips.

- "The Unicorn in the Garden", The New Yorker (31 October 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940). This is a fable where a man sees a Unicorn in his garden, and his wife reports the matter to have him taken away, to the "booby-hatch". Online text with illustration by Thurber

- Don't count your boobies until they are hatched.

- "The Unicorn in the Garden", The New Yorker (31 October 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940)

- He who hesitates is sometimes saved.

- "The Glass in the Field", The New Yorker (31 October 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940). This is the moral of a fable in which several birds reject a Goldfinch's report that he ran into "crystallized air" while flying across a field, where workmen had left a large plate of glass upright. The Swallow rejects the offer to come along with others and prove the Goldfinch wrong.

- Don't get it right, just get it written.

- "The Sheep in Wolf's Clothing", The New Yorker (29 April 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940). The moral is ironic with respect to the fable, in which sheep do insufficient research before writing about wolves, resulting in the sheep being easy prey.

- It is better to have loafed and lost, than never to have loafed at all.

- "The Courtship of Arthur and Al", The New Yorker (26 August 1939); Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940). Parody of Alfred Lord Tennyson's "Better to have loved and lost/than never to have loved at all."

- Nowadays most men lead lives of noisy desperation.

- "The Grizzly and the Gadgets", The New Yorker (date unknown); Further Fables for Our Time (1956); This statement is derived from one of Henry David Thoreau: "The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation."

- Love is blind, but desire just doesn't give a good goddam. [sic]

- "The Clothes Moth and the Luna Moth", The New Yorker (date unknown); Further Fables for Our Time (1956)

- A word to the wise is not sufficient if it doesn't make any sense.

- "The Weaver and the Worm", The New Yorker (11 August 1956); Further Fables for Our Time (1956)

- All men kill the thing they hate, too, unless, of course, it kills them first.

- "The Crow and the Scarecrow", The New Yorker (date unknown); Further Fables for Our Time (1956). This is derived from Oscar Wilde's statement "All men kill the thing they love..."

- All men should strive to learn before they die what they are running from, and to, and why.

- "The Shore and the Sea", Further Fables for Our Time (first publication, 1956)

- Moral: Where most of us end up there is no knowing, but the hellbent get where they are going.

- "The Wolf Who Went Places", The New Yorker, Page 28 (19 May 1956); Further Fables for Our Time (1956)

From other fiction

edit- The pounding of the cylinders increased: ta-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa.

- The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1942)

- "To hell with the handkerchief," said Walter Mitty scornfully. He took one last drag on his cigarette and snapped it away. Then, with that faint, fleeting smile playing about his lips, he faced the firing squad; erect and motionless, proud and disdainful, Walter Mitty the Undefeated, inscrutable to the last.

- The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1942)

- "Who are you?" the minstrel asked. "I am the Golux," said the Golux, proudly, "the only Golux in the world, and not a mere Device."

- The Thirteen Clocks (1951) page 32

From Lanterns and Lances

edit- Every time is a time for comedy in a world of tension that would languish without it. But I cannot confine myself to lightness in a period of human life that demands light ... We all know that, as the old adage has it, "It is later than you think." ..., but I also say occasionally: "It is lighter than you think." In this light let's not look back in anger, or forward in fear, but around in awareness.

- "Foreword", Lanterns & Lances (1961)

- Precision of communication is important, more important than ever, in our era of hair trigger balances, when a false or misunderstood word may create as much disaster as a sudden thoughtless act.

- Lanterns and Lances (1961), p. 44

- There are two kinds of light — the glow that illumines, and the glare that obscures.

- Lanterns and Lances (1961), p. 146; also misquoted as "There are two kinds of light — the glow that illuminates, and the glare that obscures."

- Boys are perhaps beyond the range of anybody's sure understanding, at least when they are between the ages of eighteen months and ninety years.

- "The Darlings at the Top of the Stairs", Lanterns & Lances (1961); previously appeared in The Queen and in Harper's Magazine.

- A pinch of probability is worth a pound of perhaps.

- note for "a future fable", "Such a Phrase as Drifts Through Dreams", Holiday Magazine; reprinted in Lanterns & Lances (1961).

- Now I am not a cat man, but a dog man, and all felines can tell this at a glance — a sharp, vindictive glance.

- "My Senegalese Birds and Siamese Cats", Holiday Magazine; reprinted in Lanterns & Lances (1961).

- Man has gone long enough, or even too long, without being man enough to face the simple truth that the trouble with Man is Man.

- "The Trouble with Man is Man", The New Yorker; reprinted in Lanterns & Lances (1961).

- The only rules comedy can tolerate are those of taste, and the only limitations those of libel.

- "The Duchess and the Bugs", Lanterns & Lances (1961). The piece was "a response" to an award Thurber received from the Ohioana Library Association in 1953.

- Discussion in America means dissent.

- "The Duchess and the Bugs", Lanterns & Lances (1961).

- Somebody has said that woman's place is in the wrong. That's fine. What the wrong needs is a woman's presence and a woman's touch. She is far better equipped than men to set it right.

- "The Duchess and the Bugs", Lanterns & Lances (1961).

- If I have sometimes seemed to make fun of Woman, I assure you it has only been for the purpose of egging her on.

- "The Duchess and the Bugs", Lanterns & Lances (1961).

- Humor and pathos, tears and laughter are, in the highest expression of human character and achievement, inseparable.

- "The Case for Comedy", Lanterns & Lances (1961); previously appeared in The Atlantic Monthly November 1960

- It is true, I confess, that if a male character of my invention started across the stage to disrobe a virgin criminally (ah, euphemism to end euphemisms!), he would probably catch his foot in the piano stool and end up playing "Button Up Your Overcoat" on the black keys.

- "The Case for Comedy", Lanterns & Lances (1961).

From other writings

edit- She came naturally by her confused and groundless fears, for her own mother lived the latter years of her life in the horrible suspicion that electricity was dripping invisibly all over the house.

- My Life and Hard Times (1933) page 33, Harper & Row, New York.

- In order to be eligible to play it was necessary for him to keep up in his studies, a very difficult matter, for while he was not dumber than an ox he was not any smarter.

- My Life And Hard Times, referring to a fellow Ohio State student and football star.

- I do not have a psychiatrist and I do not want one, for the simple reason that if he listened to me long enough, he might become disturbed.

- "Carpe Noctem, If You Can", Credos and Curios (1962)

- The dog has got more fun out of Man than Man has got out of the dog, for the clearly demonstrable reason that Man is the more laughable of the two animals.

- "An Introduction", The Fireside Book of Dog Stories (Simon and Schuster, 1943); reprinted in Thurber's Dogs (1955)

- The dog has seldom been successful in pulling Man up to its level of sagacity, but Man has frequently dragged the dog down to his.

- "An Introduction", The Fireside Book of Dog Stories (Simon and Schuster, 1943); reprinted in Thurber's Dogs (1955)

- I am not a dog lover. A dog lover to me means a dog that is in love with another dog.

- "I Like Dogs", For Men (April 1939); reprinted in People Have More Fun Than Anybody (1994); slightly paraphrased in "And So to Medve", Thurber's Dogs (1955)

- He picked out this sentence in a New Yorker casual of mine: "After dinner, the men moved into the living room," and he wanted to know why I, or the editors, had put in the comma. I could explain that one all right. I wrote back that this particular comma was Ross's way of giving the men time to push back their chairs and stand up.

- The Years with Ross (Little Brown & Co, 1957, pg.267)

- Variant: From one casual of mine he picked this sentence. “After dinner, the men moved into the living room.” I explained to the professor that this was Ross’s way of giving the men time to push back their chairs and stand up. There must, as we know, be a comma after every move, made by men, on this earth.

- Memo to The New Yorker (1959); reprinted in New York Times Book Review (4 December 1988); Harold Ross was the editor of The New Yorker from its inception until 1951, and well-known for the overuse of commas

- From now on, I think it is safe to predict, neither the Democratic nor the Republican Party will ever nominate for President a candidate without good looks, stage presence, theatrical delivery, and a sense of timing.

- A drawing is always dragged down to the level of its caption.

- The New Yorker (2 August 1930)

- But those rare souls whose spirit gets magically into the hearts of men, leave behind them something more real and warmly personal than bodily presence, an ineffable and eternal thing. It is everlasting life touching us as something more than a vague, recondite concept. The sound of a great name dies like an echo; the splendor of fame fades into nothing; but the grace of a fine spirit pervades the places through which it has passed, like the haunting loveliness of mignonette.

- “The Book-End,” Columbus Dispatch (1923) Collecting Himself (1989).

- Sophistication might be described as the ability to cope gracefully with a situation involving the presence of a formidable menace to one's poise and prestige (such as the butler, or the man under the bed — but never the husband).

- The New Yorker (2 August 1930), discussing cartooning

- Speed is scarcely the noblest virtue of graphic composition, but it has its curious rewards. There is a sense of getting somewhere fast, which satisfies a native American urge.

- Preface to A Thurber Garland (1955)

- Women are wiser than men, because they know less and understand more.

- Quoted in: Kabir, Hajara Muhammad (2010). Northern women development. [Nigeria]. ISBN 978-978-906-469-4. OCLC 890820657.

- [1]

Letters and interviews

edit- Comedy has to be done en clair. You can't blunt the edge of wit or the point of satire with obscurity. Try to imagine a famous witty saying that is not immediately clear.

- Letter, March 11, 1954, to Malcolm Cowley. Collecting Himself (1989)

- With 60 staring me in the face, I have developed inflammation of the sentence structure and a definite hardening of the paragraphs.

- Quoted in New York Post (30 June 1955)

- The laughter of man is more terrible than his tears, and takes more forms — hollow, heartless, mirthless, maniacal.

- New York Times Magazine (7 December 1958).

- I always begin at the left with the opening word of the sentence and read toward the right and I recommend this method.

- Memo to The New Yorker (1959); reprinted in New York Times Book Review (4 December 1988)

- When all things are equal, translucence in writing is more effective than transparency, just as glow is more revealing than glare.

- Memo to The New Yorker (1959); reprinted in New York Times Book Review (4 December 1988)

- Editing should be, especially in the case of old writers, a counseling rather than a collaborating task. The tendency of the writer-editor to collaborate is natural, but he should say to himself, "How can I help this writer to say it better in his own style?" and avoid "How can I show him how I would write it, if it were my piece?"

- Memo to The New Yorker (1959); reprinted in New York Times Book Review (4 December 1988)

- The wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; the humorist makes fun of himself, but in so doing, he identifies himself with people — that is, people everywhere, not for the purpose of taking them apart, but simply revealing their true nature.

- Television interview with Edward R. Murrow on TV show Small World, CBS-TV (25 March 1959); transcript published in New York Post

- We all know that the theater and every play that comes to Broadway have within themselves, like the human being, the seed of self-destruction and the certainty of death. The thing is to see how long the theater, the play, and the human being can last in spite of themselves.

- Quoted in New York Times (21 February 1960).

- If a playwright tried to see eye to eye with everybody, he would get the worst case of strabismus since Hannibal lost an eye trying to count his nineteen elephants during a snowstorm while crossing the Alps.

- Quoted in The New York Times (21 February 1960)

- Humor is emotional chaos remembered in tranquility.

- Quoted in New York Post (29 February 1960)

- My drawings have been described as pre-intentionalist, meaning that they were finished before the ideas for them had occurred to me. I shall not argue the point.

- Interview, Life Magazine (New York, March 14, 1960).

- I’m 65 and I guess that puts me in with the geriatrics. But if there were fifteen months in every year, I’d only be 48. That’s the trouble with us. We number everything. Take women, for example. I think they deserve to have more than twelve years between the ages of 28 and 40.

- Quoted from an an interview with Glenna Syse in Time Magazine (New York, 15 August 1960); Time's editors corrected Thurber's arithmetic

- One (martini) is all right, two is too many, three is not enough.

- Quoted in Time Magazine (New York, 15 August 1960) from an an interview with Glenna Syse of the Chicago Sun-Times

- My opposition lies in the fact that offhand answers have little value or grace of expression, and that such oral give and take helps to perpetuate the decline of the English language.

- Letter to Henry Brandon after an interview with him, explaining his opposition to interviews; quoted by Brandon in As We Are (1961)

- The difference between our decadence and the Russians is that while theirs is brutal, ours is apathetic.

- Quoted in The Observer (London, 5 February 1961).

External links

edit- Thurber's World (and Welcome To it)

- James Thurber Web Collection - includes online versions of some of his works

- Pathfinder: James Grover Thurber - collects many Thurber links

- Thurber House

- Thurber Reading - 2010·05·21 Countdown with Keith Olbermann: "The Mouse Who Went to the Country","The Moth and the Star", & "The Owl Who Was God"