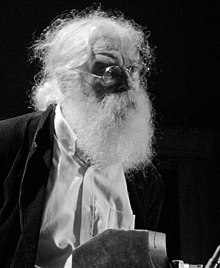

Irving Finkel

British archaeologist

Irving Leonard Finkel (born 1951 in Islington, County of London) is a British philologist, Assyriologist, author, and the Assistant Keeper of Ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and cultures in the Department of the Middle East in the British Museum.

Quotes

edit- In the years around the turn of the present century, relying on the contacts and expertise of Theophilus Goldridge Pinches, Lord William Amhurst Tyssen-Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst of Hackney (1835–1909), put together what came to be one of the most wide-ranging and important collections of cuneiform tablets to have been assembled in private hands in this country. Since the publication of Volume 1 of The Amherst Tablets in 1908 by Pinches, followed much later by E. Sollberger's The Pinches Manuscript, the Amherst Collection has been familiar enough among Assyriologists, but perhaps less has been known of the collector, and of his other collections. The Museum at the family estate of Didlington Hall, Northwold, Norfolk, contained in its heyday a much broader range of material than cuneiform inscriptions. From the Near Eastern world there were very extensive collections of Egyptian papyri and antiquities, but the Hall also housed remarkable accumulations of incunabula and printed books, porcelain, tapestries, sculpture and other works of art.

- (1996)"Tablets for Lord Amherst". Iraq 58: 191–205. DOI:10.2307/4200427.

- The Cyrus Cylinder is one of the world's best-known cuneiform inscriptions and at the same time one of the most famous archaeological objects in the British Museum in London.

- "Introduction by Irving Finkel". The Cyrus Cylinder: The Great Persian Edict from Babylon. Bloomsbury. 2013. pp. 1–3. ISBN 9780857723246; edited by Irving Finkel (quote from p. 1)

- Within the field of Assyriology the royal cuneiform libraries of Kuyunjik (ancient Nineveh), the Assyrian capital city, have no parallel for size, breadth, or document quality. ... The bulk of the library material had been put together at royal bequest with the specific intention of housing, editing, and recopying the traditional written expressions of Mesopotamian culture in, as far as possible, a complete state. Assurbanipal's long reign (668–c.627 BCE) in character was one of stability and affluence and there was ample opportunity for the pursuit and accumulation of manuscripts in abundance. Thus it fell to Austen Henry Layard and those who came after him to uncover what was in essence a 'state of the art' royal library, whose underlying conception constitutes the only rival to the lost resources of Alexandria that the ancient world can provide.

- "Chapter 9. Assurbanipal's Library. An Overview by Irving Finkel". Libraries before Alexandria: Ancient Near Eastern Traditions. Oxford University Press. 2019. pp. 367–389. ISBN 978-0-19-252399-0; edited by Kim Ryholt & Gojko Barjamovic (quote from p. 367)

- ... I think the ultimate issue about ghosts is human arrogance. The ultimate, ultimate point is that I am me — the greatest hunter in the world — nineteen wives and four hundred and thirty-two children — and the best spear thrower in the world. I'm going to die? And it's all going to be over? No way!

- (October 28, 2021)"Bettany Hughes and Irving Finkel discuss the 'The First Ghosts'". British Museum Events, YouTube. (quote at 34:41 of 1:04:58 in video)

The Ark Before Noah (2014)

edit- George Smith's discoveries led to unease in more than one quarter. It was simply bizarre that a close relative of Holy Writ should emanate from such a primitive, barbaric world through so improbable a medium, to thrust itself uncompromisingly into public consciousness. How could Noah and his Ark possibly been known and important to the Assyrians of noble Asnapper and the Babylonians of mad, dread Nebuchadnezzar? Worried people over garden fences and in church pews clamoured to have important questions answered.

- "Chapter 1. About this Book". The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. 2014. ISBN 9780385537124.

- Cuneiform! The world's oldest and hardest writing, older by far than any alphabet, written by long-dead Sumerians and Babylonians over more than three thousand years, and as extinct by the time of the Romans as any dinosaur. What a challenge! What an adventure!

- "Chapter 2. The Wedge between Us". The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood. 2014.

The First Ghosts (2021)

edit- ... I have still never seen a ghost for myself, even in the shadier vaults of the British Museum, where the ancient dead can lie peacefully, and many of the living have witnessed strange things. Sometimes I have crouched immobile in the evening darkness at the top level of our Victorian Arched Room library, like a wildlife photographer at a waterhole, waiting in silence for a spectral figure who has, they say, more than once been observed. For me, though, no shady visitor.

- "Author's Notes". The First Ghosts: A rich history of ancient ghosts and ghost stories from the British Museum curator. Hodder & Stoughton. 2021. ISBN 9781529303278.

- In contrast to mourning and burial, it is the deep-seated conception that some part of a person does not vanish forever that separates us absolutely from the whole animal kingdom. No gorilla or bald-headed eagle ever had an inkling of their inner self finishing up somewhere once the proud body had collapsed into chemicals. It is only the early human mind that grew to strive against the prospect of the final annihilation of self, a hallmark rebellion that became hard-wired into, and always an essential element of, human nature. It is the incalculable antiquity of the first stirrings towards post-mortem existence that explains the enduring and universal belief in ghosts. Ghosts have waited in the wings from the beginning and have fluttered persistently as part of human cultural, religious or philosophical baggage ever since. Practically speaking, as a result, they are inexpungible.

- "Chapter 1. Ghosts at the Beginning". The First Ghosts: A rich history of ancient ghosts and ghost stories from the British Museum curator. 2021.

External links

editEncyclopedic article on Irving Finkel on Wikipedia