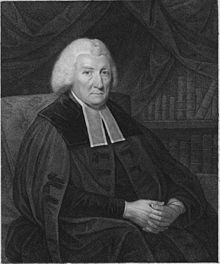

Hugh Blair

British philosopher

Hugh Blair, FRSE (7 April 1718 – 27 December 1800) was a Scottish minister of religion, author and rhetorician, considered one of the first great theorists of written discourse. As a minister of the Church of Scotland, and occupant of the Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at the University of Edinburgh, Blair's teachings had a great impact in both the spiritual and the secular realms. Best known for Sermons, a five volume endorsement of practical Christian morality, and Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres, a prescriptive guide on composition, Blair was a valuable part of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Quotes

edit- What we call human reason, is not the effort or ability of one, so much as it is the result of the reason of many, arising from lights mutually communicated, in consequence of discourse and writing.

- Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (1784), Lecture I: Introduction.

- Homer is the most simple in his style of all the great poets, and resembles most the style of the poetical parts of the Old Testament. They can have no conception of his manner, who are acquainted with him in Mr. Pope's translation only. An excellent poetical performance that translation is, and faithful in the main to the original. In some places, it may be thought to have even improved Homer. It has certainly softened some of his rudenesses, and added delicacy and grace to some of his sentiments. But withal, it is no other than Homer modernised. In the midst of the elegance and luxuriancy of Mr. Pope's language, we lose sight of the old bard's simplicity. I know indeed no author, to whom it is more difficult to do justice in a translation, than Homer.

- Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (1784), Lecture XLIII: Homer's Iliad and Odyssey—Virgil's Aeneid.

- Between levity and cheerfulness there is a wide distinction; and the mind which is most open to levity is frequently a stranger to cheerfulness.

- Reported in The Saturday Magazine (September 28, 1833), p. 118.

- Anxiety is the poison of human life ; the parent of many sins and of more miseries. – In a world where everything is doubtful, and where we may be disappointed, and be blessed in disappointment, why this restless stir and commotion of mind? – Can it alter the cause, or unravel the mystery of human events?

- Quoted in A Dictionary of Thoughts: Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors of the World, Both Ancient and Modern, ed. Tryon Edwards, F. B. Dickerson Company (1908), p. 23.

Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895)

edit- Quotes reported in Josiah Hotchkiss Gilbert, Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895).

- Look around you, and you will behold the universe full of active powers. Action is, so to speak, the genius of nature. By motion and exertion, the system of being is preserved in vigor. By its different parts always acting in subordination one to another, the perfection of the whole is carried on. The heavenly bodies perpetually revolve. Day and night incessantly repeat their appointed course. Continual operations are going on in the earth and in the waters. Nothing stands still. All is alive and stirring throughout the universe. In the midst of this animated and busy scene, is man alone to remain idle in his place? Belongs it to him to be the sole inactive and slothful being in the creation, when in so many various ways he might improve his own nature; might advance the glory of the God who made him; and contribute his part in the general good?

- P. 4.

- That discipline which corrects the baseness of worldly passion, fortifies the heart with virtuous principles, enlightens the mind with useful knowledge, and furnishes it with enjoyment from within itself, is of more consequence to real felicity, than all the provision we can make of the goods of fortune.

- P. 109.

- How shocking must thy summons be, O Death!

To him that is at ease in his possessions!

Who, counting on long years of pleasure here,

Is quite unfurnished for the world to come.

In that dread moment, how the frantic soul

Raves round the walls of her clay tenement;

Runs to each avenue, and shrieks for help;

But shrieks in vain.- P. 175.

- Dissimulation in youth is the forerunner of perfidy in old age; its first appearance is the fatal omen of growing depravity and future shame.

- P. 242.

- Idleness is the great corrupter of youth, and the bane and dishonor of middle age. He who, in the prime of life, finds time to hang heavy on his hands, may with much reason suspect that he has not consulted the duties which the consideration of his age imposed upon him; assuredly he has not consulted his happiness.

- P. 345.

- The great standard of literature as to purity and exactness of style is the Bible.

- P. 386.

- In the eye of that Supreme Being to whom our whole internal frame is uncovered, dispositions hold the place of actions.

- P. 420.

- Embellish truth only with a view to gain it the more full and free admission into your hearer's minds; and your ornaments will, in that case, be simple, masculine, natural.

- P. 481.

- In whatever light we view religion it appears solemn and venerable. It is a temple full of majesty, to which the worshiper may approach with comfort, in the hope of obtaining grace and finding mercy; but where they cannot enter without being inspired with awe. If we may be permitted to compare spiritual with natural things, religion resembles not those scenes of natural beauty where every object smiles. It cannot be likened to the gay landscape or the flowery field. It resembles more the august and sublime appearances of Nature — the lofty mountain, the expanded ocean, and the starry firmament; at the sight of which the mind is at once overawed and delighted; and, from the union of grandeur with beauty, derives a pleasing but a serious devotion.

- P. 493.

- The spirit of true religion breathes gentleness and affability; it gives a native, unaffected ease to the behavior; it is social, kind, cheerful; far removed from the cloudy and illiberal disposition which clouds the brow, sharpens the temper, and dejects the spirit.

- P. 501.

- The slave who digs in the mine or labors at the oar can rejoice at the prospect of laying down his burden together with his life; but to the slave of guilt there arises no hope from death. On the contrary, he is obliged to look forward with constant terror to this most certain of all events, as the conclusion of all his hopes, and the commencement of his greatest miseries.

- P. 550.