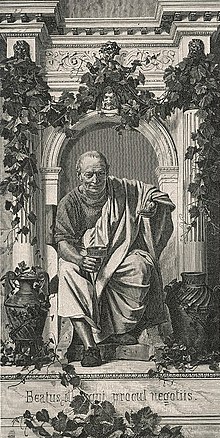

Horace

Roman lyric poet

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading lyric poet in Latin.

Quotes

edit- Cras ingens iterabimus aequor

- Tomorrow we will be back on the vast ocean.

- The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations: The Illiterati's Guide to Latin Maxims, Mottoes, Proverbs and Sayings

- Tomorrow we will be back on the vast ocean.

- Quamquam ridentem dicere verum quid vetat? ut pueris olim dant crustula blandi doctores, elementa velint ut discere prima.

- What is to prevent one from telling truth as he laughs, even as teachers sometimes give cookies to children to coax them into learning their A B C?

- Book I, satire i, line 24 (translation by H. Fairclough)

- What odds does it make to the man who lives within Nature's bounds, whether he ploughs a hundred acres or a thousand?

- Book I, satire i, line 48

- Bona pars hominum est decepta cupidine falso 'nil satis est', inquit, 'quia tanti quantum habeas sis.'

- People are enticed by a desire which continually cheats them.

‘Nothing is enough,’ they say, ‘for you’re only worth what you have.’ - Book I, satire i, lines 61-62, as translated by N. Rudd

- People are enticed by a desire which continually cheats them.

- Saepe stilum vertas, iterum quae digna legi sint scripturus.

- Often must you turn your pencil to erase, if you hope to write something worth a second reading.

- Book I, satire i, lines 72-3, (transl. Rushton Fairclough, 1926)

- Let’s put a limit to the scramble for money. ...

Having got what you wanted, you ought to begin to bring that struggle to an end.- Book I, satire i, lines 92-94, as translated by N. Rudd

- Inde fit ut raro, qui se vixisse beatum

dicat et exacto contentus tempore vita

cedat uti conviva satur, reperire queamus.- We rarely find anyone who can say he has lived a happy life, and who, content with his life, can retire from the world like a satisfied guest.

- Book I, satire i, line 117

- Non satis est puris versum perscribere verbis.

- 'Tis not sufficient to combine

Well-chosen words in a well-ordered line. - Book I, satire iv, line 54 (translated by John Conington)

- 'Tis not sufficient to combine

- Atqui si vitiis mediocribus ac mea paucis

mendosa est natura, alioqui recta, velut si

egregio inspersos reprehendas corpore naevos,

si neque avaritiam neque sordes nec mala lustra

obiciet vere quisquam mihi, purus et insons,

ut me collaudem, si et vivo carus amicis...

at hoc nunc

laus illi debetur et a me gratia maior.

nil me paeniteat sanum patris huius, eoque

non, ut magna dolo factum negat esse suo pars,

quod non ingenuos habeat clarosque parentis,

sic me defendam.- If my character is flawed by a few minor faults, but is otherwise decent and moral, if you can point out only a few scattered blemishes on an otherwise immaculate surface, if no one can accuse me of greed, or of prurience, or of profligacy, if I live a virtuous life, free of defilement (pardon, for a moment, my self-praise), and if I am to my friends a good friend, my father deserves all the credit... As it is now, he deserves from me unstinting gratitude and praise. I could never be ashamed of such a father, nor do I feel any need, as many people do, to apologize for being a freedman's son.

- Book I, satire vi, lines 65–92

- Nil sine magno

vita labore dedit mortalibus.- Life grants nothing to us mortals without hard work. / Life has given nothing to mortals without great labor.

- Book I, satire ix, line 59

- in pace, ut sapiens, aptarit idonea bello

- In peace, as a wise man, he should make suitable preparation for war.

- Book II, satire ii, line 111

- In peace, as a wise man, he should make suitable preparation for war.

- Adclinis falsis animus meliora recusat.

- The mind enamored with deceptive things, declines things better.

- Book II, satire ii, line 6

- The mind enamored with deceptive things, declines things better.

- Quocirca vivite fortes, fortiaque adversis opponite pectora rebus

- So live, my boys, as brave men; and if fortune is adverse, front its blows with brave hearts.

- Book II, Satire II, Line 135-136 (trans. E. C. Wickham)

- So live, my boys, as brave men; and if fortune is adverse, front its blows with brave hearts.

- Ille sinistrorsum, hic dextrorsum abit : unus utrique

Error, sed variis illudit partibus.- This to the right, that to the left hand strays,

And all are wrong, but wrong in different ways. - Book II, satire iii, line 50 (trans. Conington)

- This to the right, that to the left hand strays,

- Heu, Fortuna, quis est crudelior in nos

Te deus? Ut semper gaudes illudere rebus Humanis!- O Fortune, cruellest of heavenly powers,

Why make such game of this poor life of ours? - Book II, satire viii, line 61 (trans. Conington)

- O Fortune, cruellest of heavenly powers,

- Sed convivatoris uti ducis ingenium res

Adversae nudare solent, celare secundae.- A host is like a general: calamities often reveal his genius.

- Book II, satire viii, lines 73–74 [1]

- Dum licet, in rebus jucundis vive beatus;

Vive memor quam sis aevi brevis.- Then take, good sir, your pleasure while you may;

With life so short 'twere wrong to lose a day. - Book II, satire viii, line 96 (trans. Conington)

- Then take, good sir, your pleasure while you may;

- Nequiquam deus abscidit

Prudens Oceano dissociabili

Terras, si tamen impiae

Non tangenda rates transiliunt vada.- In vain did Nature's wife command

Divide the waters from the land,

If daring ships and men profane,

Invade th' inviolable main. - Book I, ode iii, line 21 (trans. by John Dryden)

- In vain did Nature's wife command

- Vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat inchoare longam.

- Life's short span forbids us to enter on far reaching hopes.

- Book I, ode iv, line 15

- Nil desperandum...

- Never despair...

- Book I, ode vii, line 27

- Nunc vino pellite curas.

- Now drown care in wine.

- Book I, ode vii, line 32

- Permitte divis cetera.

- Leave all else to the gods.

- Book I, ode ix, line 9

- Dum loquimur, fugerit invida

Aetas: carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero.- As we speak cruel time is fleeing. Seize the day, believing as little as possible in the morrow.

- Book I, ode xi, line 7

- John Conington's translation:

- In the moment of our talking, envious time has ebbed away,

Seize the present, trust tomorrow e'en as little as you may.

- In the moment of our talking, envious time has ebbed away,

- O matre pulchra filia pulchrior

- O fairer daughter of a fair mother!

- Book I, ode xvi, line 1

- Nunc est bibendum, nunc pede libero

pulsanda tellus.- Now is the time for drinking, now the time to dance footloose upon the earth.

- Book I, ode xxxvii, line 1

- Aequam memento rebus in arduis

servare mentem.- In adversity, remember to keep an even mind.

- Book II, ode iii, line 1

- Auream quisquis mediocritatem

diligit, tutus caret obsoleti

sordibus tecti, caret invidenda

sobrius aula.- Whoever cultivates the golden mean avoids both the poverty of a hovel and the envy of a palace.

- Book II, ode x, line 5

- Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume,

labuntur anni nec pietas moram

rugis et instanti senectae

adferet indomitaeque morti.- Ah, Postumus! they fleet away,

Our years, nor piety one hour

Can win from wrinkles and decay,

And Death's indomitable power. - Book II, ode xiv, line 1 (trans. John Conington)

- Ah, Postumus! they fleet away,

- Virginibus puerisque canto.

- I sing for maidens and boys.

- Book III, ode i, line 4

- Aequa lege Necessitas

Sortitur insignes et imos;

Omne capax movet urna nomen.- Death takes the mean man with the proud;

The fatal urn has room for all. - Book III, ode i, line 14 (trans. John Conington)

- Death takes the mean man with the proud;

- Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.

- It is sweet and honorable to die for one's country.

- Book III, ode ii, line 13

- Iustum et tenacem propositi virum

non civium ardor prava iubentium,

non vultus instantis tyranni

mente quatit solida.- The man who is tenacious of purpose in a rightful cause is not shaken from his firm resolve by the frenzy of his fellow citizens clamoring for what is wrong, or by the tyrant's threatening countenance.

- Book III, ode iii, line 1

- Si fractus illabatur orbis,

impavidum ferient ruinae.- If the world should break and fall on him, it would strike him fearless.

- Book III, ode iii, line 7

- Vis consili expers mole ruit sua.

- Force without wisdom falls of its own weight.

- Come, Mercury, by whose minstrel spell

Amphion raised the Theban stones,

Come, with thy seven sweet strings, my shell,

Thy "diverse tones,"

Nor vocal once nor pleasant, now

To rich man's board and temple dear:

Put forth thy power, till Lyde bow Her stubborn ear.- Mercui, Nam Te

- Book III, ode xi

- Crescentem sequitur cura pecuniam,

Maiorumque fames.- As money grows, care follows it and the hunger for more.

- Book III, ode xvi, line 17

- Magnas inter opes inops.

- A pauper in the midst of wealth.

- Book III, ode xvi, line 28.

- Conington's translation: "'Mid vast possessions poor."

- Quod adest memento

componere aequus.- Enjoy the present smiling hour,

And put it out of Fortune's power. - Book III, ode xxix, line 32 (as translated by John Dryden)

- Enjoy the present smiling hour,

- Ille potens sui

laetusque deget, cui licet in diem

dixisse "vixi: cras vel atra

nube polum pater occupato

vel sole puro."- He will through life be master of himself and a happy man who from day to day can have said, "I have lived: tomorrow the Father may fill the sky with black clouds or with cloudless sunshine."

- Book III, ode xxix, line 41

- John Dryden's paraphrase:

Happy the man, and happy he alone,

He, who can call to day his own:

He who, secure within, can say,

To-morrow do thy worst, for I have lived to-day.

- John Dryden's paraphrase:

- Exegi monumentum aere perennius

- I have made a monument more lasting than bronze.

- Book III, ode xxx, line 1

- Pulvis et umbra sumus.

- We are but dust and shadow.

- Book IV, ode vii, line 16

- Vixere fortes ante Agamemnona.

- Brave men were living before Agamemnon.

- Book IV, ode ix, line 25

- Quid verum atque decens curo et rogo, et omnis in hoc sum.

- My cares and my inquiries are for decency and truth, and in this I am wholly occupied.

- Book I, epistle i, line 11

- Nullius addictus iurare in verba magistri,

quo me cumque rapit tempestas, deferor hospes.- I am not bound over to swear allegiance to any master; where the storm drives me I turn in for shelter.

- Book I, epistle i, line 14

- Virtus est vitium fugere et sapientia prima

stultitia caruisse.- To flee vice is the beginning of virtue, and to have got rid of folly is the beginning of wisdom.

- Book I, epistle i, line 41

- Nos numerus sumus et fruges consumere nati.

- We are but numbers, born to consume resources.

- Book I, epistle ii, line 27

- Nam cur

quae laedunt oculum festinas demere; si quid

est animum, differs curandi tempus in annum?- For why do you hasten to remove things that hurt your eyes, but if anything gnaws your mind, defer the time of curing it from year to year?

- Book I, epistle ii, lines 37–39; translation by C. Smart

- For why do you hasten to remove things that hurt your eyes, but if anything gnaws your mind, defer the time of curing it from year to year?

- Dimidium facti qui coepit habet; sapere aude;

incipe!- He who has begun has half done. Dare to be wise; begin!

- Book I, epistle ii, lines 40–41

- Qui recte vivendi prorogat horam,

Rusticus exspectat dum defluat amnis.- He who postpones the hour of living rightly is like the rustic who waits for the river to run out before he crosses.

- Book I, epistle ii, lines 41–42

- Semper avarus eget.

- The covetous man is ever in want.

- Book I, epistle ii, line 56

- Ira furor brevis est: animum rege: qui nisi paret

imperat.- Anger is a momentary madness so control your passion or it will control you.

- Book I, epistle ii, line 62

- Inter spem curamque, timores inter et iras,

Omnem crede diem tibi diluxisse supremum:

Grata superveniet quae non sperabitur hora.- Let hopes and sorrows, fears and angers be,

And think each day that dawns the last you'll see;

For so the hour that greets you unforeseen

Will bring with it enjoyment twice as keen. - Book I, epistle iv, line 12 (translated by John Conington)

- Let hopes and sorrows, fears and angers be,

- Omnem crede diem tibi diluxisse supremum.

grata superveniet, quae non sperabitur hora.- Think to yourself that every day is your last; the hour to which you do not look forward will come as a welcome surprise.

- Book I, epistle iv, line 13–14

- Me pinguem et nitidum bene curata cute vises,

cum ridere voles Epicuri de grege porcum.- As for me, when you want a good laugh, you will find me in fine state... fat and sleek, a true hog of Epicurus' herd.

- Book I, epistle iv, lines 15–16

- Naturam expellas furca, tamen usque recurret.

- You may drive out Nature with a pitchfork, yet she still will hurry back.

- Book I, epistle x, line 24

- Caelum, non animum mutant, qui trans mare currunt.

- Sky, not spirit, do they change, those who cross the sea.

- Book I, epistle xi, line 27

- Pauper enim non est, cui rerum suppetit usus.

si ventri bene, si lateri est pedibusque tuis, nil

divitiae poterunt regales addere maius.- He is not poor who has enough of things to use. If it is well with your belly, chest and feet, the wealth of kings can give you nothing more.

- Book I, epistle xii, line 4

- Quid velit et possit rerum concordia discors

- What the discordant harmony of circumstances would and could effect.

- Book I, epistle xii, line 19

- Nam neque divitibus contingunt gaudia solis,

nec vixit male, qui natus moriensque fefellit.- For joys fall not to the rich alone, nor has he lived ill, who from birth to death has passed unknown.

- Book I, epistle xvii, line 9

- Sedit qui timuit ne non succederet.

- He who feared that he would not succeed sat still.

- Book I, epistle xvii, line 37

- Semel emissum volat irrevocabile verbum.

- Once a word has been allowed to escape, it cannot be recalled.

- Book I, epistle xviii, line 71

- Qualem commendes, etiam atque etiam aspice, ne mox incutiant aliena tibi peccata pudorem.

- Look round and round the man you recommend,

For yours will be the shame should he offend. - Book I, epistle xviii, line 76 (translated by John Conington).

- Variant translation: Study carefully the character of the one you recommend, lest his misdeeds bring you shame.

- Look round and round the man you recommend,

- Nam tua res agitur, paries cum proximus ardet.

- It is your concern when your neighbor's wall is on fire.

- Book I, epistle xviii, line 84

- Dulcis inexpertis cultura potentis amici; Expertus metuit.[2]

- To have a great man for an intimate friend seems pleasant to those who have never tried it; those who have, fear it.

- Book I, epistle xviii, line 86

- Interdum volgus rectum videt, est ubi peccat.

- At times the world sees straight, but many times the world goes astray.

- Book II, epistle i, line 63

- Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artes intulit agresti Latio.

- Conquered Greece took captive her savage conqueror and brought her arts into rustic Latium.

- Book II, epistle i, lines 156–157

- Singula de nobis anni praedantur euntes.

- The years as they pass plunder us of one thing after another.

- Book II, epistle ii, line 55

- Natales grate numeras?

- Do you count your birthdays with gratitude?

- Book II, epistle ii, line 210

Ars Poetica, or The Epistle to the Pisones (c. 18 BC)

edit- Inceptis gravibus plerumque et magna professis

purpureus, late qui splendeat, unus et alter

adsuitur pannus.- Often a purple patch or two is tacked on to a serious work of high promise, to give an effect of colour.

- Line 14

- Brevis esse laboro,

obscurus fio.- Struggling to be brief I become obscure.

- Line 25

- Non satis est pulchra esse poemata; dulcia sunto

Et, quocumque uolent, animum auditoris agunto.- Mere grace is not enough: a play should thrill

The hearer's soul, and move it at its will. - Line 99 (tr. John Conington)

- Mere grace is not enough: a play should thrill

- Si vis me flere, dolendum est

primum ipsi tibi.- If you wish me to weep, you yourself

Must first feel grief. - Line 102

- If you wish me to weep, you yourself

- Format enim Natura prius nos intus ad omnem

Fortunarum habitum, juvat, aut impellit ad iram,

Aut ad humum moerore gravi deducit, et angit.- For nature forms our spirits to receive

Each bent that outward circumstance can give:

She kindles pleasure, bids resentment glow,

Or bows the soul to earth in hopeless woe. - Line 108 (tr. Conington)

- For nature forms our spirits to receive

- Difficile est proprie communia dicere.

- It is difficult to speak of the universal specifically.

- Line 128

- Nec verbum verbo curabis reddere fidus

Interpres.- Nor word for word too faithfully translate.

- Line 133 (tr. John Dryden)

- Parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus.

- The mountains will be in labor, and a ridiculous mouse will be brought forth.

- Line 139. Horace is hereby poking fun at heroic labours producing meager results; his line is also an allusion to one of Æsop's fables, The Mountain in Labour.

- Cf. Matthew Paris (AD 1237): Fuderunt partum montes: en ridiculus mus.

- In medias res.

- Into the middle things.

- Line 148

- Et quae

Desperat tractata nitescere posse relinquit.- And what he fears he cannot make attractive with his touch he abandons.

- Line 149 (tr. H. R. Fairclough)

- Scribendi recte sapere est et principium et fons.

- To have good sense, is the first principle and fountain of writing well.

- Line 309

- To have good sense, is the first principle and fountain of writing well.

- Grais ingenium, Grais dedit ore rotundo

Musa loqui, præter laudem nullius avaris. . .- The Muse gave the Greeks their native character, and allowed them to speak in noble tones, they who desired nothing but praise.

- Line 323

- Quidquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta

percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles:

omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat.- When you wish to instruct, be brief; that men’s minds may take in quickly what you say, learn its lesson, and retain it faithfully. Every word that is unnecessary only pours over the side of a brimming mind.

- Lines 335–337; Edward Charles Wickham translation

- When you wish to instruct, be brief; that men’s minds may take in quickly what you say, learn its lesson, and retain it faithfully. Every word that is unnecessary only pours over the side of a brimming mind.

- Omne tulit punctum qui miscuit utile dulci,

lectorem delectando pariterque monendo.- He wins every hand who mingles profit with pleasure, by delighting and instructing the reader at the same time.

- Line 343

- ... Siquid tamen olim scripseris, in Maeci descendat iudicis auris et patris et nostras, nonumque prematur in annum membranis intus positis; delere licebit quod non edideris; nescit uox missa reuerti.

- But if ever you shall write any thing, let it be submitted to the ears of Metius [Tarpa], who is a judge, and your father’s, and mine; and let it be suppressed till the ninth year, your papers being laid up within your own custody. You will have it in your power to blot out what you have not made public: a word once sent abroad can never return.

- lines 386-390

- Sunt delicta tamen quibus ignovisse velimus.

- Some faults may claim forgiveness.

- Line 347 (tr. Conington)

- Indignor quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus;

- I am displeased when sometimes even the worthy Homer nods;

- Whence the familiar expression, Even Homer nods (i.e. No one is perfect: even the wisest make mistakes).

- Line 359

- Mediocribus esse poetis Non homines, non di, non concessere columnae.

- Mediocrity in poets has never been tolerated by either men, or gods, or booksellers.

- Lines 372–373

- Nec satis apparet, cur versus factitet.

- None knows the reason why this curse

Was sent on him, this love of making verse. - Line 470 (tr. Conington)

- None knows the reason why this curse

Classical and Foreign Quotations

edit- Quotes reported in Classical and Foreign Quotations (1904)

- Abnormis sapiens crassaque Minerva.

- Of strong good sense, untutored in the schools.

- Ep. 2, 2, 3.

- i.e., Full of mother-wit.

- Of strong good sense, untutored in the schools.

- Ab ovo Usque ad mala.

- From the eggs to the apples.

- S. 1, 3, 6.

- From beginning to end: “eggs and apples” being respectively the first and last courses at a Roman dinner. The phrase applies to any topic, or speaker, that monopolises the whole of the conversation.

- From the eggs to the apples.

- Absentem qui rodit amicum,

Qui non defendit alio culpante, solutos

Qui captat risus hominum, famamque dicacis;

Fingere qui non visa potest, commissa tacere

Qui nequit, hic niger est, hunc tu, Romane, caveto.- The man that will malign an absent friend,

Or when his friend’s attacked, does not defend;

Who seeks to raise a laugh, be thought a wit;

Declares “he saw,” when he invented it;

Who blabs a secret—Roman, friend, take care!

His heart is black, of such a man beware.- S. 1, 4, 81.

- A Blackguard.

- The man that will malign an absent friend,

- Adsit Regula, peccatis quæ pœnas irroget æquas

Ne scutica dignum horribili sectere flagello.- Be just: and mete to crime its condign pain;

Nor use the murd’rous lash where suits the cane.- S. 1, 3, 117.

- Be just: and mete to crime its condign pain;

Misattributed

edit- Ars longa, vita brevis.

- Art is long, life is short.

- Seneca's (De Brevitate Vitae, 1.1) Latin translation of the Greek by Hippocrates.

External links

edit- Works by Horace at Project Gutenberg

- The works of Horace at The Latin Library

- Selected Poems of Horace

- The Perseus Project — Latin and Greek authors (with English translations), including Horace

- Biography and chronology

- Horace at Litweb

- Horace's works – text, concordances and frequency list

- SORGLL: Horace, Odes I.22, read by Robert Sonkowsky