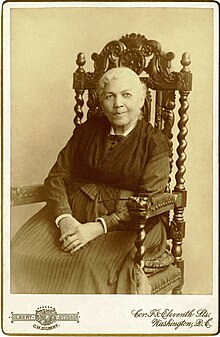

Harriet Jacobs

Harriet Jacobs (1813 or 1815 – March 7, 1897) was an African-American writer, whose autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent, is now considered an "American classic". Born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina, she was sexually harassed by her enslaver. When he threatened to sell her children if she did not submit to his desire, she hid in a tiny crawl space under the roof of her grandmother's house, so low she could not stand up in it. After staying there for seven years, she finally managed to escape to the free North, where she was reunited with her children Joseph and Louisa Matilda and her brother John S. Jacobs. She found work as a nanny and got into contact with abolitionist and feminist reformers. Even in New York, her freedom was in danger until her employer was able to pay off her legal owner.

During and immediately after the Civil War, she went to the Union-occupied parts of the South together with her daughter, organizing help and founding two schools for fugitive and freed slaves.

Quotes

edit- We are passing through times that will secure for us a higher and nobler celebration. American gold will never secure freedom equal rights and justice to our race. No! before these can come American slavery must be crushed, and its foul stain wiped from the Nation[‘]s escutcheon.

- speech (August 1, 1864)

- Notwithstanding my grandmother's long and faithful service to her owners, not one of her children escaped the auction block. These God-breathing machines are no more, in the sight of their masters, than the cotton they plant, or the horses they tend.

- p. 16

- I met my grandmother, who said, "Come with me, Linda;" and from her tone I knew that something sad had happened. She led me apart from the people, and then said, "My child, your father is dead." ... The good grandmother tried to comfort me. "Who knows the ways of God?" said she. "Perhaps they have been kindly taken from the evil days to come." Years afterwards I often thought of this. She promised to be a mother to her grandchildren, so far as she might be permitted to do so; and strengthened by her love, I returned to my master's. I thought I should be allowed to go to my father's house the next morning; but I was ordered to go for flowers, that my mistress's house might be decorated for an evening party. I spent the day gathering flowers and weaving them into festoons, while the dead body of my father was lying within a mile of me. What cared my owners for that? he was merely a piece of property. Moreover, they thought he had spoiled his children, by teaching them to feel that they were human beings.

- p. 18

- I would ten thousand times rather that my children should be the half-starved paupers of Ireland than to be the most pampered among the slaves of America. I would rather drudge out my life on a cotton plantation, till the grave opened to give me rest, than to live with an unprincipled master and a jealous mistress. The felon's home in a penitentiary is preferable. He may repent, and turn from the error of his ways, and so find peace; but it is not so with a favorite slave. She is not allowed to have any pride of character. It is deemed a crime in her to wish to be virtuous.

- p. 49

- The secrets of slavery are concealed like those of the Inquisition. My master was, to my knowledge, the father of eleven slaves. But did the mothers dare to tell who was the father of their children? Did the other slaves dare to allude to it, except in whispers among themselves? No, indeed! They knew too well the terrible consequences.

- p. 55

- O virtuous reader! You never knew what it is to be a slave; to be entirely unprotected by law or custom; to have the laws reduce you to the condition of a chattel, entirely subject to the will of another. You never exhausted your ingenuity in avoiding the snares, and eluding the power of a hated tyrant; you never shuddered at the sound of his footsteps, and trembled within hearing of his voice.

- p. 86

Quotes about Harriet Jacobs

edit- My favorite collection of slave narratives was a nineteen-volume set called The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography. It was assembled in the 1930s by the Writer's Project [of the Works Progress Administration], and these people interviewed the slaves who were left, the very last ones. It was depressing reading not only because bad things happened to slaves, but because slavery could become so pedestrian when you read enough of it, so ordinary. I remember someone telling me that they'd read the Harriet Jacobs narrative, and they said it was mild compared to other slave narratives. And, horribly enough, it was, but that doesn't make her any less a slave. It wasn't something you'd want to undergo.

- 2003 interview in Conversations with Octavia Butler

- (The last book that made you cry?) “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” by Harriet Jacobs.

- Zadie Smith Interview (2016)