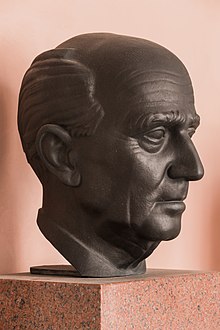

Hans Kelsen

Austrian lawyer (1881–1973)

Hans Kelsen (October 11, 1881 – April 19, 1973) was an Austrian jurist, legal philosopher and political philosopher.

Quotes

edit- The mark of Platonic philosophy is a radical dualism. The Platonic world is not one of unity; and the abyss which in many ways results from this bifurcation appears in innumerable forms. It is not one, but two worlds, which Plato sees when with the eyes of his soul he envisages a transcendent, spaceless, and timeless realm of the Idea, the thing-in-itself, the true, absolute reality of tranquil being, and when to this transcendent realm he opposes the spacetime sphere of his sensuous perception-a sphere of becoming in motion, which he considers to be only a domain of illusory semblance, a realm which in reality is not-being.

- "Platonic Justice", Ethics, April 1938. Translated by Glenn Negley from "Die platonische Gerechtigkeit," Kantstudien, 1933. (The author corrected the translation in 1957), published in What is Justice? (1957)

- Law is an order of human behavior. An “order” is a system of rules. Law is not, as it is sometimes said, a rule. It is a set of rules having the kind of unity we understand by a system. It is impossible to grasp the nature of law if we limit our attention to the single isolated rule.

- General Theory of Law and State (1949), I. The Concept of Law, A. Law and Justice, a. Human Behavior as the Objects of Rules

- Justice is primarily a possible, but not a necessary, quality of a social order regulating the mutual relations of men. Only secondarily it is a virtue of man, since a man is just, if his behavior conforms to the norms of a social order supposed to be just. But what does it really mean to say that a social order is just? It means that this order regulates the behavior of men in a way satisfactory to all men, that is to say, so that all men find their happiness in it. The longing for justice is men's eternal longing for happiness. It is happiness that men cannot find alone, as an isolated individual, and hence seeks in society. Justice is social happiness. It is happiness guaranteed by a social order.

- "What Is Justice?" (1952), published in What is Justice? (1957)

- One of the most important elements of Christian religion is the idea that justice is an essential quality of God. Since God is the absolute, his justice must be absolute justice, that is to say, eternal and unchangeable. Only a religion whose deity is supposed to be just can play a role in social life. To attribute justice to the deity in order to make religion applicable to human relations implies a certain tendency of rationalizing something which, by its very nature, is irrational-the transcendental being, the religious authority, and its absolute qualities.

- "The Idea of Justice in the Holy Scriptures", Rivista Juridicade la Universidadde Puerto Rico, Sept., 1952-April, 1953., published in What is Justice? (1957)

- It is called a “pure” theory of law, because it only describes the law and attempts to eliminate from the object of this description everything that is not strictly law: Its aim is to free the science of law from alien elements. This is the methodological basis of the theory.

- Pure Theory of Law (revised ed., 1960), 1. The “Pure” Theory

- By determining law — so far as it is the subject of a specific science of law — as norm, it is delimited against nature; and science of law against natural science. But in addition to legal norms, there are other norms regulating the behavior of men to each other, that is, social norms; and the science of law is therefore not the only discipline directed toward the cognition and description of social norms. There other social norms may be called “morals.” and the discipline directed toward their cognition and description, “ethics.” So far as justice is a postulate of morals, the relationship between justice and law is included in the relationship between morals and law.

- Pure Theory of Law (revised ed., 1960), 7. Moral Norms as Social Norms

Quotes about Kelsen

edit- The characterization of Kelsen’s pure theory of law as an ideology is here not meant as a reproach, though its defenders are bound to regard it as such. Since every social order rests on an ideology, every statement of the criteria by which we can determine what is appropriate law in such an order must also be an ideology. The only reason why it is important to show that this is also true of the pure theory of law is that its author prides himself on being able to ‘unmask’ all other theories of law as ideologies and to have provided the only theory which is not an ideology. This Ideolologie-kritik is even regarded by some of his disciples as one of Kelsen’s greatest achievements. Yet, since every cultural order can be maintained only by an ideology, Kelsen succeeds only in replacing one ideology with another that postulates that all orders maintained by force are orders of the same kind, deserving the description (and dignity) of an order of law, the term which before was used to describe a particular kind of order valued because it secured individual freedom. Though within his system of thought his assertion is tautologically true, he has no right to assert, as he constantly does, that other statements in which, as he knows, the term ‘law’ is used in a different sense, are not true. What ‘law’ is to mean we can ascertain only from what those who used the word in shaping our social order intended it to mean, not by attaching to it some meaning which covers all the uses ever made of it. Those men certainly did not mean by law, as Kelsen does, any ‘social technique’ which employs force, but used it in order to distinguish a particular ‘social technique’, a particular kind of restraint on the use of force, which by the designation of law they tried to distinguish from others. The use of enforceable generic rules in order to induce the formation of a self-maintaining order and the direction of an organization by command towards particular purposes are certainly not the same ‘social techniques’. And if, because of accidental historical developments, the term ‘law’ has come to be used in connection with both these different techniques, it should certainly not be the aim of analysis to add to the confusion by insisting that these different uses of the word must be brought under the same definition.

- Friedrich Hayek, Law, Legislation and Liberty, Vol. 2. The Mirage of Social Justice (1976), Chap. 8 : The Quest of Justice