Golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

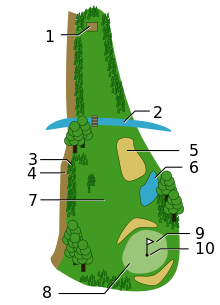

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not utilize a standardized playing area, and coping with the varied terrains encountered on different courses is a key part of the game. The game at the usual level is played on a course with an arranged progression of 18 holes, though recreational courses can be smaller, often having nine holes. Each hole on the course must contain a tee box to start from, and a putting green containing the actual hole or cup 4 1⁄4 inches (11 cm) in diameter. There are other standard forms of terrain in between, such as the fairway, rough (long grass), bunkers (or "sand traps"), and various hazards (water, rocks) but each hole on a course is unique in its specific layout and arrangement.

The players relied on the rabbits and the sheep to keep the grass short-cropped, for it was not until the early part of the twentieth century that mechanised grass cutting began to take over from the animals in golf course management. Indeed many of Britain's seaside links, Saunton sands in Devon being a classic example, relied exclusively on rabbits to keep their fairways tightly cropped until well into the second half of the twentieth century when the myxomatosis epidemic of the 1950s killed so many of the rabbits off. ~ Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley

However, it was not until the latter half of the nineteenth century that the game really began to spread outwards from Scottland with the main reason the improvement in the transport system provided by the expanding network in Britain.

The railway gave enthusiasts access to the existing courses in Scotland, and to the newly developed victorian seaside resorts in England, as well as north of the border. The first trains ran into St Andrews as early as 1850 but towards the latter part of the century, seaside towns built gold courses as an attraction to visitors and the railway gave easy access to them. It is no accident that virtually all of the great links golf courses of Britain have had, or still have, a railway line running along one of their boundaries.

Golf then moved inland where courses were built within train distance of the cities to meet the demand for this newly popular game. ~ Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley

However, we have to go back much further than that to find the first woman player in Scotland.

That honour belongs to Mary Queen of Scots, mother of James VI of Scotland and I of England, and a notable player around the middle of the sixteenth century. Evidence of her keenness on the game is revealed in the account of one of her matches with one of her attendants, Mary Seaton, which the Queen lost, she presented her conqueror with a famous necklace.

The Queen most famously encountered the wrath of the Church for playing golf on the fields of Seton in 1567 only a few days after the death of her husband, Lord Darnley, father of James VI. ~ Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley

Even the most experienced ball maker could only manufacture four feather balls in a day, which accounted for their price of three to four shillings, a huge sum at the time and more even than the cost of a golf club. ~ Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley

Quotes

edit- Golf? Nuts! I never did see any fun in a game, where if I hit a ball, I had to chase it myself.

- Ping Bodie, as quoted in "Ping Bodie Once Ruth's Outfield Mate" by Bill Henry, Los Angeles Times (May 2, 1937), p. 22

- As the game developed, separate teeing grounds were eventually established and the golf course in the form we know it today gradually began to emerge.

The players relied on the rabbits and the sheep to keep the grass short-cropped, for it was not until the early part of the twentieth century that mechanized grass cutting began to take over from the animals in golf course management. Indeed many of Britain's seaside links, Saunton sands in Devon being a classic example, relied exclusively on rabbits to keep their fairways tightly cropped until well into the second half of the twentieth century when the myxomatosis epidemic of the 1950s killed so many of the rabbits off.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 16

- There were no club makers of course in the early days of the game but golfers found that the skills of the weapons makers could be pressed into service, particularly those of the bow makers who made the bows which King James II was so keen for his populace to use in preference to golf clubs.

The bow makers became the first club makers, manufacturing crude but effective implements first for the wooden balls used until the early seventeenth century, and then more sophisticated clubs to deal with the feather ball, the first major development in golf equipment.

The bow makers who first began the development of the slender, fragile, long-nosed wooden clubs that held sway until the arrival of the gutta percha ball in the middle of the nineteenth century, were club makers in their own right, and examples of the fine work of the best of them, such as McEwan and Philip and Tom Morris himself, command considerable sums in the present day.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 16-17

- In the beginning the golf ball was made of wood, probably of beech, but the feather ball, or 'featherie' came into existence around 1618, marking the first ball improvement in golf.

The feather ball was made in Scotland for more than 200 years until it was superseded by the gutta percha ball in 1848.

It was expensive and easily damaged and the single element that dictated that the game was played in its earliest stages by the wealthier sections of the community who could afford the price of the golf balls.

The task of crafting a featherie was not only arduous for the ball makers of the time, but very detrimental to their health. The ball maker's lungs were filled with feather dust and the constant pressure on the chest of forcing the boiled feathers into the small leather pouch with a special crutch-handled filling rod, took its toll.

Even the most experienced ball maker could only manufacture four geather balls in a day, which accounted for their price of three to four shillings, a huge sum at the time and more even than the cost of a golf club.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 17

- The game of golf as we know it today did not really emerge from its crude beginnings on the east coast of Scotland until it began to become organised around the middle of the eighteenth century. Clubs began to be formed devoted exclusively to golf, and with them the development of a generally accepted set of rules.

The first golf club for which there is definite proof of origin is the Gentlemen Golfers of Leith, now the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers at Muirfield, instituted in 1744. * There is no record of any rules attaching to the earliest form of the game of golf, although it is safe to assume that there had to be some from the very beginning. It was not until a formal competition among players arrived with the representation to the Gentlemen Golfers of Leith of a silver club from the City Council of Edinburgh for annual competition, that there was a need to agree to a set of rules under which the competition would be played.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 18.

- Today golf is an international game played in every corner of the world. It owes that popularity to the pioneering efforts of Scottish golfers in the nineteenth century who built upon the early framework of organisation and spread the gospel of golf with the enthusiasm and dedication of missionaries.

As we have already seen thee game had witnessed some early movement out of Scotland to other golfing outposts, taken by royalty to England as far back as the early seventeenth century, by Scottish merchants to far away places like India, where the Royal Calcutta Golf Club dates back to 1829, and by the armed forces to South Carolina in the United States, where golf was played long before the famous Apple Tree Gang founded the first American golf club at Yonkers in New York in 1888. these, however, were isolated pockets; golf was very much vested in the hands of the Scots, and virtually confined within Scotland's borders, until well into the nineteenth century.

The reasons were simple: only the Scots knew how to play, they had the skills to manufacture the clubs and balls required to play; they were the only nation then with any experience of laying out a course upon which to play and relatively poor communications and transport had, broadly speaking left the game as yet unexposed to the wider world.

Two things changed all that. Firstly the discovery that the rubber from a gutta percha tree could be easily and cheaply moulded into a much more servicable golf ball than the expensive 'featherie', the only option until 1848, thus opening the game up to a much wider audience. Secondly there was the rapid expansion of the Victorian era which brought new prosperity to the middle classes and with it an improved transport system. Many of the now mobile English middle class imitated the royal family by holidaying in Scotland, where they discovered the delights of golf and then took the game back with them south of the border.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 22

- Wherever they traveled Scotts took their favorite pastime with them. They set up courses and founded golf clubs. None made a more significant contribution to the mass explosion of golf in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, than two expatriate Scottish school friends from Dunfermline in Fife, John Reid and Robert Lockhart, although neither is likely to have realised it at the time. Reid is regarded as the 'father of American golf', as we will see later, but Lockhart had a significant part to play as well.

While Reid was introducing golf to the United States, essentially for the first time, the game was spreading like wildfire in the British Isles. Scottish professionals were imported south of the border into England and to Ireland and Wales to lay out courses to meet the new demand for the game.

A measure of the demand for their services is the huge increase evident in the number of golf clubs founded in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Prior to that period the majority of clubs were in Scotland. In 1864 there were about 30 golf clubs in Scotland while in england there were only three - Royal Blackheath, old Machester and Westward Ho! By 1880 there were 60 clubs in Britain; by 1890 there were 387 and by the start of the new millennium Britain had almost 2500 clubs. The Scots pioneers had done their work well.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 24

- Although there is no written evidence so far traced of golf before James II's Act of Parliament of 1457, there is no doubt that a form of the game was being played in St Andrews as far back as the thirteenth century and perhaps even further back than that.

However, it was not until the latter half of the nineteenth century that the game really began to spread outwards from Scottland with the main reason the improvement in the transport system provided by the expanding network in Britain.

The railway gave enthusiasts access to the existing courses in Scotland, and to the newly developed Victorian seaside resorts in England, as well as north of the border. The first trains ran into St Andrews as early as 1850 but towards the latter part of the century, seaside towns built golf courses as an attraction to visitors and the railway gave easy access to them. It is no accident that virtually all of the great links golf courses of Britain have had, or still have, a railway line running along one of their boundaries.

Golf then moved inland where courses were built within train distance of the cities to meet the demand for this newly popular game.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 24

- The first Scot who tried to influence the game to any real extent did not attempt to do so for the betterment of the game at all; in fact he went to some lengths to try to stop it altogether. Perhaps it was an early example of the Scots perversity in 'forbidding themselves to do what they want to do', as George Pottinger commented in his excellent account of the history of the Honourable Company, that King James II issues an infamous decree banning the game altogether in 1457.

It had no effect of course, for the Scots had more interest in putting their wits against the links than in entertaining any fear of His Majesty's wrath because of their refusal to practice archery for defence of the nation at a time when the King was warring on several fronts. Even the threat of being taken by the 'King's officiars' was not sufficient to curtail the golfing desires of the populace.

Fourteen years later another Royal decree, this time by King James II's successor, James III, commanding that 'fute-ball and be abused in time coming', had as little effect on the population as the first one, and when James IV tried to ban the game again twenty years later he got just as short shrift.

There was at least some salvation for James IV, for he took to the game himself after signing a treaty of Perpetual Peace with England, presumably making the requirement for archery practice less pressing in the process. His Treaty may have been a victory for hope over experience before or since, but at least it gave him some breathing space after having had the sense to take to the links himself.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 26

- Golf in the early days as it became organised was very much the preserve of the wealthier classes, professional and military men and the landed genry who not only had the time to play but the wherewithal to afford the cost of early equipment, particularly feather golf balls which were incredibly expensive.

The first golf club members were therefore gentlemen of substance and it was not until the arrival of the much less expensive gutta percha ball in 1848 that the game had a chance to expand into the wider community. As it did so the demand for more courses and for teachers became imperative, and golf began to see the emergence of the professional. These men who made golf their business arrived from the ranks of the caddies, who had previously carried the clubs of their gentlemen employers, and from the ball makers like the first professional, Allan Robertson, who kept the gentlemen players supplied with their expensive feather balls.

Golf was able to cross the barriers of class as in no other walk of life. Great matches were played between sides composed of gentlemen players and professionals. Allan Robertson and Old Tom Morris and Willie and Jamie Dunn of Musselburgh often did battle with huge sums of money resting on the outcome. Large crowds used to follow the matches and betting was often heavy on the result.

As the game expanded quickly in the second half of the nineteenth century, money matches, and eventually tournaments, were eventually held for professional players only. The first of consequence was the Open Championship of 1860, restricted to professional players with caddies who had to be supervised by gentlemen 'markers' to ensure that the rules of golf were strictly adhered to. When the gentlemen players were allowed to play in the event the following years, the professionals were still required to have markers, but the gentlemen players were trusted entirely to conduct themselves appropriately on the links.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 33

- Scottish women have made a significant contribution to the development of golf since the middle of the nineteenth century. The Ladies' Golf Club of St Andrews was formed in 1867 and by 1886 there were 500 members.

By 1872, the St Andrews Ladies' Spring and Autumn Meetings had become important events with a gold medal and the Douglas Prize open for competition. Miss Mary Lamb and her sister Miss May Lamb, Miss A. Boothby and Miss F. Hume McLeod were the leading players in the early days of the club and regular winners of the medals.

However, we have to go back much further than that to find the first woman player in Scotland.

That honour belongs to Mary Queen of Scots, mother of James VI of Scotland and I of England, and a notable player around the middle of the sixteenth century. Evidence of her keeness on the game is revealed in the account of one of her matches with one of her attendants, Mary Seaton, which the Queen lost, she presented her conqueror with a famous necklace.

The Queen most famously encountered the wrath of the Church for playing golf on the fields of Seton in 1567 only a few days after the death of her husband, Lord Darnley, father of James VI.- Malcolm Campbell, Glyn Satterley, “The Scottish Golf Book”, (1999), p. 36

- According to the Environmental Protection Agency, “[T]he average American family of four uses 400 gallons of water per day.” The average golf course uses 312,000 gallons of water, according to Audobon International, meaning each one uses as much water as 780 families of four. In Palm Springs—immediately adjacent to a place called Palm Desert—NPR reported that each of the city's 57 courses use about a million gallons a day, or about the same as 2,500 families of four.

Looking statewide, the numbers really get fun. California is second only to Florida in the number of golf courses it has: 921. Together, those courses use as much water as 2.8 million people, or about 7 percent of the state's population. While middle-class homeowners risk fines for watering their lawns, millions upon millions of gallons of water are wasted every day on a boring leisure sport for the wealthy.

“Golf courses are a huge problem,” said Adam Keats of the Center for Biological Diversity, an environmental advocacy group. And part of that huge problem is the people who play it. “They're a wealthy elite that have no connection to want or lack,” Keats, head of the center's California Water Law Project, told me over the phone. “Golfers live in a world of excess.”- Charles Davis, “Instead of Killing Lawns, We Should Be Banning Golf”, Vice, (Aug 15 2014).

- Applying the principles of art to golf course design obviously contributes a sense of well-being to those golfers who are playing with the objectives of relaxing and enjoying themselves. On the other hand, touring professionals out to win concentrate on getting the ball into the tiny hole and may be forced to ignore beautiful surroundings. Yet one suspects that the beauty of a course provides even them with relaxation during periods of extreme stress. This sense of well-being may be somewhat similar to the feeling of security that arises in people from having mowed lawns surrounding their dwellings. Perhaps that feeling harks back to a need to see one's prey or enemy at a distance through a focal point past trees and over short grass.

An evolutionary biologist has told the authors that most golfers play the game in order to relax and enjoy themselves, and there may be biological reasons that the landscape design of golf courses contributes to these feelings. The human species spent most of its history as hunter-gathers in habitats like those of golf courses, only much larger-specifically, open savannas, grasslands with scattered trees and bushes that supply nutritious food (browsing and grazing animals, berries, seeds, buried roots), shade from the sun, refuges where we can stalk prey and hide from predators, and frequent changes in elevation than enable us to orient in space and thus find out way to remembered places that provide important resources, such as food, water, and shelter. Evolutionary biologists and psychologist, such as Orians and Heerwargen, have found a preference for such savanna-like landscapes across human cultures, ad they suggest that it reflects an evolved learning bias that allowed us to psychologically adapt to living in this habitat. We could invent challenging golf like games in which balls are hit through habitats that are much less expensive to maintain, such as dense woods, open land that is flat and barren, or a desert, which would be one continuous sand trap! But we don't , and part of the reason for not doing so is that such landscapes are just not appealing to the majority of our species and do not provide that sense of well-being that golf architects strive to create.- Robert Muir Graves, Geoffrey S. Cornish, “Classic Golf Hole Design: Using the Greatest Holes as Inspiration for Modern Courses", (2002), p. 10

- It is worth repeating that the principles of art have little or no connection to the original links of Scotland, although the latter resemble savannas whose wildly undulating terrain represents the opposite or arrangement. In fact, the first classic holes did not arise naturally from the land- but came about when greenkeepers and professionals modified it. Through logical thinking and good taste, these pioneering designers employed principles of art they had probably never heard of.

- In the beginning, playing fields were needed for golf, and more space was required than for the somewhat similar games that had preceded it. Early sites took the form of city streets, frozen lakes, and then entrancing seashores. These were crafted by nature and by society, but they were discovered by golfers. As the popularity of golf grew, however, so too did people's desire to shape their playing fields.

In today's game, where professional architects carefully plot and plan every detail of a new layout, it's nearly impossible to comprehend the prospect of "discovering" a ready-made golf course. And today's golfers might not recognize the earliest natural playing fields as being in any way related to today's manicured courses. Nor did the games themselves always resemble golf. There were a variety of forebearers to the game we know today. Some passed in and out of existence; others evolved; others migrated across international borders. Over hundreds of years, those games rattled around like balls ina lottery drawing until, from all of these, came golf.- Robert Muir Graves, Geoffrey S. Cornish, “Classic Golf Hole Design: Using the Greatest Holes as Inspiration for Modern Courses", (2002), p. 15

- Beginning with pagancia in ancient Rome, golf has had many ancestors in many distant lands, all similar in one way or another to the game we know today. These now long-lost pastimes included chole (soule in Belgium), with similarities to both hockey and gold, kolven in the Netherlands, sometimes played on ice and a game whose name may have evolved into the word "golf"; and pall-mall (also called mail, pele male, jeu de mail), a game played first in the streets of Italy before spreading across Europe and finally arriving in Scotland. The impact of these games on the modern architecture of gold is remote, if it exists as all; yet they made golf possible.

An informative account of these pregolf games is presented by Robert Browning in his History of Golf: The Royal and Ancient Game. He says that "It was the Scots who devised the essential features of gold, the combination of hitting for distance with the final nicety of approach to an exigous mark, and the independent progress of each player with his own ball free from interference by his adversary."- Robert Muir Graves, Geoffrey S. Cornish, “Classic Golf Hole Design: Using the Greatest Holes as Inspiration for Modern Courses", (2002), pp. 15-16

- With the development of rail travel, it became possible for clubs to cast a wider net and attract leading golfers to a single tournament. The Prestwick Golf Clubs suggests in 1856 that a Grand National Tournament between all the leading clubs should be held. Clubs agreed to hold the tournament at St. Andrews a year later, in July 1857. The event was organized as a team event with a pair of players from each club playing a knockout competition over 30 holes. Eleven clubs were represented. The pair of George Glennie and John Campbell Stewart of Blackheath took the title, being awarded a silver jug.

- Like modern sports generally, golf began to surge in popularity in the latter part of the 19th century, spreading far beyond its Scottish origins. The first Amateur Championship was held in 1885, and this, along with the patronage of leading figures, notably the politician and later Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, led to a middle-class boom in golfing all over Britain and beyond. Real wages rose by over 60 percent between 1870 and 1890, which also expanded the middle class and gave more people disposable income. Golf grew from about 60 clubs in 1870 to nearly 2,800 by 1909. In 1898, the Golfing Annual reported that it could not keep up with development, as 283 clubs reported events in 1897, while 1,750 did so in 1898. Women began to play as well, and there were 30 ladies' clubs by 1890 and 18 courses specifically for women players. By 1914, this had grown to 450 clubs and over 45 courses. In the London area, the 30 golf clubs of 1890 grew to over 300 by 1909, with ease of travel by train, bicycle, and automobile making more and more courses possible and accessible. Similar factors helped golf's expansion in the United States, with the 16 clubs of 1893 ballooning to 1,040 by 1901.

- John Nauright, Charles Parrish, “Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice, Volume 2”, (2012), p. 101

- Golf course location and design also began to change. By 1914 over 90 percent of courses were inland and the golf course designer came into vogue, led by a quartet of early designers, such as the Heathland Quartet of Willie Park Jr. H.S. Colt, Herbery Forlwer, and J. F. Abercromby. Design and maintenance of grounds, the need for equipment, and operations led to a full-grown golf industry. British demand soon expanded around the world, with dramatic upsurges in gold courses and clubs in North America and continental Europe by 1900 as well as areas of British influence in Asia, Africa, South America, and Australasia. The expansion of golf also provided opportunities for young Scotsmen in particular. It has been estimated that more than 2000 Carnoustie men were hired as professionals by golf clubs around the world by 1900.

- John Nauright, Charles Parrish, “Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice, Volume 2”, (2012), pp. 101-102.

- By the early 1900s golf was an essential cultural activity of the British middle and upper classes. Rail companies used golfing destinations such as North Berwick, St. Andrews, and later Carnouystie and Dornoch, to promote golfing holidays and rail travel.

- In Ireland, modern golf began in Belfast in 1881 in the north and at the Curragh in 1883 in the south. In 1888, a club was founded that became the Royal Portrush Golf Club in 1895 in County Antrim in Northern Ireland. In 1951, it hosted the Open Championship, the only course outside of Great Britain to host the tournament. Royal Portrush is rated one of the best courses in the world.

- John Nauright, Charles Parrish, “Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice, Volume 2”, (2012), p. 102.

- The National Insurance Act of 1923 forced many clubs to cease direct employment of caddies. Improved course management and greens keeping forced smaller and weaker clubs to cease operations as players gravitated to the best courses. The expansion of motor car use also affected the rail companies. The line through Ayrshire to Turnberry ceased operation in 1930, for example. The Great Depression of the 1930s followed by World War II, and austerity measures of the 1950s had a negative impact on golf, as economic hard times and war limited the numbers who could play. War measures meant that lesser-used rail lines and old golf clubs were collected to add to steel needed for the war effort. Many clubhouses were used by the military, and gasoline rationing meant that clubs could not cut fairways of greens as frequently as they would like. Even the 9-hole course that Andrew Carnegie had constructed as Skibo Castle near Dornoch was used for food production during the war. Other courses suffered similar fates. Some courses like St. Andrews and Dunbar survived by using the courses for sheep or cattle grazing. Turnberry's course was temporarily converted to an air field. Consequently, British golfing performances at the top level also suffered. There was a brief revival in the late 1930s and again in the 1980s, which coincided with improved success by British and Irish golfers in tournament play.

- John Nauright, Charles Parrish, “Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice, Volume 2”, (2012), p. 104.