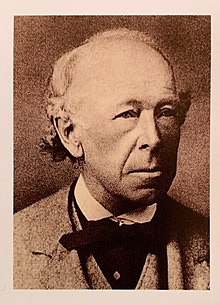

George Long (scholar)

English classical scholar (1800-1879)

George Long (November 4, 1800 – August 10, 1879) was an English classical scholar, historian and translator. Among other works, he translated of the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius (1862), the Discourses of Epictetus (1877), Plutarch's Lives (1844–1848) and was the author of the Decline of the Roman Republic (1864–1874), the Civil Wars of Rome, and the Summary of Herodotus (1829).

Quotes

editThe Philosophy of Antoninus

edit- Note: The Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus

- In the wretched times from the death of Augustus to the murder of Domitian, there was nothing but the Stoic philosophy which could console and support the followers of the old religion under imperial tyranny and amidst universal corruption.

- The doctrines of Epictetus and Antoninus are the same, and Epictetus is the best authority for the explanation of the philosophical language of Antoninus and the exposition of his opinions.

- Epictetus addressed himself to his hearers in a continuous discourse and in a familiar and simple manner. Antoninus wrote down his reflections for his own use only, in short unconnected paragraphs, which are often obscure.

- The Stoics made three divisions of philosophy, Physic, Ethic, and Logic. ...It appears, however, that this division was made before Zeno's time and acknowledged by Plato. ...Logic is not synonymous with our term Logic in the narrower sense of that word.

- Cleanthes, a Stoic, subdivided the three divisions, and made six: Dialectic and Rhetoric, comprised in Logic; Ethic and Politic; Physic and Theology. This division was merely for practical use, for all Philosophy is one.

- Even among the earliest Stoics, Logic or Dialectic does not occupy the same place as in Plato: it is considered only as an instrument which is to be used for the other divisions of Philosophy.

- According to the subdivision of Cleanthes, Physic and Theology go together, or the study of the nature of Things, and the study of the nature of the Deity, so far as man can understand the Deity, and of his government of the universe. This division or subdivision is not formally adopted by Antoninus, for... there is no method in his book; but it is virtually contained in it.

- Cleanthes also connects Ethic and Politic, or the study of the principles of morals and the study of the constitution of civil society.

- Antoninus does not treat of Politic. His subject is Ethic, and Ethic in its practical application to his own conduct in life as a man and as a governor. His Ethic is founded on his doctrines about man's nature, the Universal Nature, and the relation of every man to everything else. It is therefore intimately and inseparably connected with Physic or the Nature of Things and with Theology or the Nature of the Deity.

- He [Marcus Aurelius Antoninus] advises us to examine well all the impressions on our minds and to form a right judgment of them, to make just conclusions, and to inquire into the meanings of words, and so far to apply Dialectic, but he has no attempt at any exposition of Dialectic, and his philosophy is in substance purely moral and practical. ...an examination implies a use of Dialectic, which Antoninus accordingly employed as a means towards establishing his Physical, Theological, and Ethical principles.

- Besides the want of arrangement in the original [work of Marcus Aurelius] and of connection among the numerous paragraphs, the corruption of the text, the obscurity of the language and the style, and sometimes perhaps the confusion in the writer's own ideas - besides all this there is occasionally an apparent contradiction in the emperor's thoughts, as if his principles were sometimes unsettled, as if doubt sometimes clouded his mind.

- A man who leads a life of tranquillity and reflection, who is not disturbed at home and meddles not with the affairs of the world, may keep his mind at ease and his thoughts in one even course. But such a man has not been tried. All his Ethical philosophy and his passive virtue might turn out to be idle words, if he were once exposed to the rude realities of human existence.

- Fine thoughts and moral dissertations from men who have not worked and suffered may be read, but they will be forgotten. No religion, no Ethical philosophy is worth anything, if the teacher has not lived the "life of an apostle," and been ready to die "the death of a martyr." "Not in passivity [the passive affects], but in activity, lie the evil and the good of the rational social animal, just as his virtue and his vice lie not in passivity, but in activity" (IX. 16).

- The emperor Antoninus was a practical moralist. From his youth he followed a laborious discipline, and though his high station placed him above all want or the fear of it, he lived as frugally and temperately as the poorest philosopher.

- Epictetus wanted little, and it seems that he always had the little that he wanted, and he was content with it, as he had been with his servile station. But Antoninus after his accession to the empire sat on an uneasy seat. … what must be the trials, the troubles, the anxiety, and the sorrows of him who has the world's business on his hands with the wish to do the best that he can, and the certain knowledge that he can do very little of the good which he wishes.

- The emperor says that life is smoke, a vapour, and St. James in his Epistle is of the same mind; that the world is full of envious, jealous, malignant people, and a man might be well content to get out of it.

- He [Marcus Aurelius] has doubts perhaps sometimes even about that to which he holds most firmly. There are only a few passages of this kind, but they are evidence of the struggles which even the noblest of the sons of men had to maintain against the hard realities of his daily life.

- He [Marcus Aurelius] constantly recurs to his fundamental principle that the universe is wisely ordered, that every man is a part of it and must conform to that order which he cannot change, that whatever the Deity has done is good, that all mankind are a man's brethren, that he must love and cherish them and try to make them better, even those who would do him harm.

- This is his [Marcus Aurelius Antoninus'] conclusion (II. 17): "What then is that which is able to conduct a man? One thing and only one, Philosophy. But this consists in keeping the divinity within a man free from violence and unharmed, superior to pains and pleasures, doing nothing without a purpose nor yet falsely and with hypocrisy, not feeling the need of another man's doing or not doing anything; and besides, accepting all that happens and all that is allotted, as coming from thence, wherever it is, from whence he himself came; and, finally, waiting for death with a cheerful mind as being nothing else than a dissolution of the elements of which every living being is compounded. But if there is no harm to the elements themselves in each continually changing into another, why should a man have any apprehension about the change and dissolution of all the elements [himself]? for it is according to nature; and nothing is evil that is according to nature."

- He [Marcus Aurelius]... plainly distinguishes between Matter, Material things, and Cause, Origin, Reason. This is conformable to Zeno's doctrine that there are two original principles of all things, that which acts and that which is acted upon. That which is acted on is the formless matter: that which acts is the reason, God, who is eternal and operates through all matter, and produces all things.

M. Aurelius Antoninus

edit- A prudent governor will not roughly oppose even the superstitions of his people, and though he may wish they were wiser, he will know that he cannot make them so by offending their prejudices.

- Besides the fact of the Christians rejecting all the heathen ceremonies, we must not forget that they plainly maintained that all the heathen religions were false. The Christians thus declared war against the heathen rites, and it is hardly necessary to observe that this was a declaration of hostility against the Roman government, which tolerated all the various forms of superstition that existed in the empire, and could not consistently tolerate another religion, which declared that all the rest were false and all the splendid ceremonies of the empire only a worship of devils.

- Our extant ecclesiastical histories are manifestly falsified, and what truth they contain is grossly exaggerated; but the fact is certain that in the time of M. Antoninus the heathen populations were in open hostility to the Christians, and that under Antoninus' rule men were put to death because they were Christians.

- He did not make the rule against the Christians, for Trajan did that; and if we admit that he would have been willing to let the Christians alone, we cannot affirm that it was in his power, for it would be a great mistake to suppose that Antoninus had the unlimited authority, which some modern sovereigns have had. His power was limited by certain constitutional forms, by the senate, and by the precedents of his predecessors. We cannot admit that such a man was an active prosecutor, for there is no evidence that he was, though it is certain that he had no good opinion of the Christians, as appears from his own words. But he knew nothing of them except their hostility to the Roman religion, and probably thought they were dangerous to the state.

- I could have made the language [in the translation of Meditations] more easy and flowing, but I have preferred a ruder style as being better suited to express the character of the original.

- The last reflection of the Stoic philosophy that I have observed is in Simplicius' "Commentary on the Enchiridion of Epictetus." Simplicius was not a Christian, and such a man was not likely to be converted at a time when Christianity was grossly corrupted. But he was a really religious man, and he concludes his commentary with a prayer to the Deity which no Christian could improve.

- From the time of Zeno to Simplicius, a period of about nine hundred years, the Stoic philosophy formed the characters of some of the best and greatest men. Finally it became extinct, and we hear no more of it til the revival of letters in Italy.

- Epictetus and Antoninus have had readers ever since they were first printed. The little book of Antoninus has been the companion of some great men.

- A man's greatness lies not in wealth and station, as the vulgar believe, not yet in his intellectual capacity, which is often associated with the meanest moral character, the most abject servility to those in high places and arrogance to the poor and lowly; but a man's true greatness lies in the consciousness of an honest purpose in life, founded on a just estimate of himself and everything else, on frequent self-examination, and a steady obedience to the rule which he knows to be right, without troubling himself, as the emperor [Marcus Aurelius] says he should not, about what others may think or say, or whether they do or do not do that which he thinks and says and does.

An Old Man's Thoughts on Many Things

editOf Education I

edit- The chief business of education... is to attempt to form good habits in children, to improve the understanding, and to check the formation of bad habits.

- Great abilities are rare, and they are often accompanied by qualities which make the abilities useless to him who has them, and even injurious to society.

- I have heard it maintained that it is always the teacher's fault if a boy does not learn, even a stupid and idle boy; but I leave the decision of this matter to the "communis sensus," the common intelligence of mankind.

- Out of... average boys, if they are well brought up, come some of the most useful men to society, and sometimes great men; for the apparent dulness or slowness of some boys is only apparent: they do not apprehend quickly, because they see difficulties which sharper boys do not see, but when they emerge from the hide-bound state, they go on at a great rate, soberly and steadily. These boys become the men whom we trust... with weighty matters.

- I am daily more amazed at the ignorance of grown-up men and women, called gentlemen and gentlewomen, who, with so many means at their command, are little better than Hottentots in disguise. ...These people may read a newspaper, which is the best thing that they do read... But the chief reading of these silly people is stories, tales, novels, and works of some kind of fiction, and not even the best works of the kind. They are very much in the state of those who commit excess in strong drink.

- The deplorable condition of many of our people on whom much money has been spent is mainly owing to their wretched education, during which they have tasted of many things, but have relished nothing, learned nothing well, and have been turned out with the unhappy conceit in their heads that they have been educated, because they think that they have learned something.

- It is an undoubted truth that, if a thing is not learned well, there is more harm done than good acquired.

- The amount of our school learning can never be very great, and the value of it is allowed by all good judges to be in the discipline by which we learn, in the strengthening of the mental powers, and in the formation of character. He who learns even one thing well acquires a measure by which he may estimate himself and others: he knows what he does know, and he knows that he does not know that which he does not know. He is not deceived about himself, nor does he attempt to deceive others, nor is he likely to be deceived by others. He has attained the one sure element out of which improvement will come. All the knowledge, which we attempt to acquire and which we do really acquire, is the foundation of our character and the safe foundation on which must rest all that we shall learn afterwards and all that we shall do.

- It is almost useless to warn against this multiplicity of subjects which now distract boys and perplex teachers. The experiment of teaching a little of all things must be tried: it is demanded by opinion, founded on small or no reflection, it is required by competition for prizes, distinctions, and places; and it is encouraged by examinations and the questions proposed, which direct in a manner the course of education.

- The preparation for these examinations is a forcing system, a straining of the memory, a loading of the head with more than it can hold, and much more than it can understand, followed, as in bodily excesses, by disorder of function, addling of the brain, and the stoppage of healthy mental growth. The weak, who work hard to obtain their object, are damaged; the strong may suffer little or nothing, but they do not gain much. Those do best who do not trouble themselves about the matter, but do as well as they can and care not about success or failure.

- When I look at the number of things which a boy must now learn, or is encouraged to learn, and when I look at the questions in the examination papers, I am quite content that I was brought up in other days; and that if I did not learn much and was taught next to nothing, I have kept to old age the sense, whatever it may be, which came with me into the world.

- I think it is a truth, and an important truth, that the fundamentals of all school teaching ought to be the same.

- We have, all of us, with a few unlucky exceptions, for which special schools are required, hands, eyes, and ears; and all these members should be trained and practiced in elementary education, as a means of improving the use of these organs, and so improving the great organ which directs and oversees the work of hands, eyes, and ears, and judges of its own work and its own acts.

- All education which is in its kind complete and good, is the means of forming character, and of making useful men and women.

- Prometheus... found the human race in a pitiable condition. They saw, he says, but they really saw not: they heard, but they understood not: they were like the phantoms of our dreams, and their labour was useless and unprofitable.

- Every man who observes, must have seen what bad listeners most people are. Inability to attend carefully to what is spoken is a great defect, which leads to blunders, misrepresentation, and sometimes to quarrels.

- A few have a great power of listening and attending, but they are only few, and this power gives them a superiority over those who cannot attend.

- The inability to listen and to attend is of course a mental defect; but habit may make the defect so great, that a man's ears may almost lose the faculty of hearing what another man says, and he may be able to hear only the sweet sound of his own voice. Such incapable people are generally great talkers, very tiresome, and bad companions. They cannot be debaters in public assemblies, and can only deliver themselves of their own words.

- A man who attempts to debate when he cannot listen must make a wretched display of impotence.

- The power of attending to what is spoken, or in other words the power of listening, is one of the most useful habits that we can acquire; it keeps the mind active, and we can thus learn not only by hearing, but by reading and reflection, by fixing our minds steadily on the matter which we wish to master. It is... in a great degree, the sure means of success in all that we undertake; and if the power is not acquired early in life, great labour will be necessary to acquire it afterwards.

- This power of attention is that which perhaps more than any thing else distinguishes those who do great things from those who can do nothing well.

- Those are useful games which exercise the hand and the eye at the same time, and thus do part of the business which the schoolmaster is too ignorant or too learned to do. Games are also played according to certain rules, and thus unruly boys are taught to respect order and discipline even in their play. I hope I shall be excused if I say that boys' play is sometimes the best thing that they do at school. But let there be reasonable limits to it. Moderation in all things is the golden precept; let there be excess in nothing, not even in book learning.

- By drawing an object the children will also learn a fundamental doctrine of philosophy; but I don't recommend letting them know what the doctrine is. They will discover it some time. We do not draw objects as they are: we draw them as they seem to be. To the eye things are what they seem to be, but they are in reality, if you know what that means, something else.

- Some distinguished philosophers think that boys' eyes should be taught or trained to the examination of objects: in other words, that boys should be taught to observe things and to see likeness and difference. It is done to some extent by all boys: their games teach them something, and they know a cake from an apple. But the power of careful, patient looking at a thing is not fully acquired without some pains on the part of a teacher. When a boy reads aloud, he must look carefully at the words and letters, or he will blunder. This is an instance of observation. But the philosophers mean, I believe, that we should introduce certain things called sciences into school teaching.

- If anything is well taught—I will take Latin for example—a boy is easily led to see, indeed he cannot help seeing, certain resemblances in words. The first part of words may differ from one another, but the tails or endings may be the same; and a boy easily learns to observe these like endings and to see also that they add to or qualify the meaning of the words to which they are attached. This fact appears in our own language, and the observation of likeness and unlikeness of this kind may be taught in the humblest schools. It is a very potent method of forming boys to observe, to distinguish and to classify.

- What must we do with these sciences in schools—I mean the elementary part of them? for... the amount which we can teach in a school to the ordinary kind of boys, that is the very great majority, is not much.

- We must do something to lead boys to look at the wonderful objects by which we are surrounded, and to examine them carefully. I don't think that lectures are of much use. They will now and then amuse, and may teach boys a little; and if the lectures are followed by examinations, they will teach more.

- Real learning... is a thing in which the learner is not a receiver only of words written or spoken: he must be a doer.

- I am not a man of science, and I do not wish to be thought so. If I were, I would rather not have the name. There are men, named men of science, for whom I have great respect; there are many for whom I have no respect.

- We cannot work without matter to work on, and we must look round and see what there is. There is a material which will never fail. It is perhaps eternal, at least for us. It costs nothing, and it is everywhere. Raise your eyes on a clear night and look at the magnificent spectacle of the starry heavens... Would it be asking too much to ask masters occasionally to direct their pupils to the observation of the most splendid sight which the sons of men have had before their eyes ever since they have trod the earth?—to point out the position and tell the names of some of the brightest of these wondrous objects; to show the apparent motion of these bodies, to point out the polar star, and to lead by slow and sure steps to the conclusion which the genius of man has drawn from this apparent motion, and other considerations.

- Could not a boy be taught the elements of astronomy at the sole cost of using his eyes and his brain; taught slowly, certainly, and not wearied with too much at once? Some would learn more than others; but all would learn something. This is real science, real knowledge, which will make a boy wiser, and probably better too. He will learn to observe carefully, and not to be deceived, as we sometimes are, by appearances.

- The difficulty is to find teachers, particularly in the humble kind of schools, who can explain the elements of astronomy; but if teachers were taught such matters, they could explain them to others, and some of the teachers would be better employed in this way than in learning and teaching other things. ...I believe that many children in the humblest schools will observe and learn as well as those in other schools. When children are younger, we must use other ways of training the eye to observe.

- If we want a subject that is nearer, I think botany is the best. I do not mean classification of plants. I mean their structure, growth, propagation, parts, and uses. ...I know no other thing which presents the same facilities in the way of material, and the opportunities of seeing and handling it. I have heard that a great botanist, who lived in our time, used to teach some village children to gather and examine plants.

- I have said nothing about religious teaching as one of the means of forming a good character. ...I, who am not a teacher of religion, do not presume to say how it should be taught, so taught as to be practical. If you merely teach dogmas dogmatically, you are not teaching in the sense in which I understand teaching... and learning... does not consist merely in knowing: it is not learning unless there is some corresponding doing.

- In whatever way you who teach may manage this business, I advise you not to trust too much to the inculcation of creeds and dogmas by words written or spoken.