Fermentation in food processing

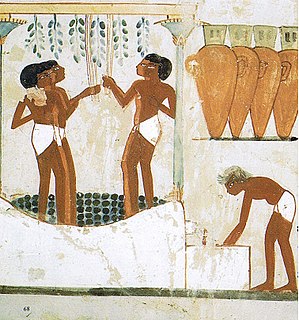

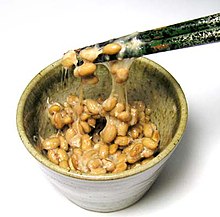

Fermentation in food processing changes the character of foods for the purposes of improved preservation, the production of alcohol and vinegar, or for the amelioration of nutrition or flavor characteristics. The fermentation converts carbohydrates to alcohol or organic acids via microorganisms—yeasts and bacteria—generally under anaerobic conditions. Molds (fungus) such as Aspergillus oryzae (koji), used in the production of sake, miso, and soy sauce, or Bacillus subtilis for Nattō, may also be involved. The science of fermentation is known as zymology or zymurgy. Fermentation may refer specifically to the conversion of sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide by yeasts, in the production of bread or beverages such as wine, beer, and cider. However, fermentations involving Lactobacillales, i.e., lactic acid producing bacteria (LAB), in products such as sauerkraut, yogurt and cheese, are also included. Fermented foods may also be exemplified by vinegar, fermented pickles, olives, and salami. Beans, grain, vegetables, fruit, honey, tea, dairy products, fish, and meats have all been used as growth and culture media in the fermentation process.

Quotes

edit- Rejuvelac is a fermented beverage that originated from Ann Wigmore's life work. ...Wigmore highly promoted rejuvelac as a form of "living water." ...Although she primarily fermented wheat... any grain can be used. ...Ann Wigmore's recipe... used unsprouted grain... Other rejuvelac recipes use sprouted grains. ...by sprouting the grains the flavor is far superior and tastes lightly lemony. The key... is to sprout the grains first and then blend them for the fermenting process. ...Fill the jar with clean filtered water ...scrape any foam or debris off the top of the liquid.

- Katrina Blair, The Wild Wisdom of Weeds: 13 Essential Plants for Human Survival (2014)

- Schwann (1837) the codiscoverer of the yeast cell, showed by experiment that fermentation and putrefaction were of microbial origin. He also disproved spontaneous generation: with sterile flasks and media he demonstrated that it was microorganisms in the air that produced putrefaction or fermentation of substances. Alcohol was produced when yeast was added to a sugar solution. When sterile media were exposed to the air, they decomposed, but if air was sterilized by heat, no decomposition occurred. Schwann reasoned that the air contained living germs that produced the putrefaction because arsenic and mercuric chloride, which were known to kill living things, also prevented putrefaction. These were the same kind of experiments Pasteur was to perform a quarter-century later. Schwann was the originator but Pasteur got the recognition. This is not to belittle Pasteur, whose many achievements earned him his place in history.

- Seymour Stanton Block, Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation (2001) Introduction: Historical Review

- Dill pickles and pearl onions are salted with just enough salt to plasmolyze the harmful organisms, and alcohol is generated first, then follows acetic and lactic fermentations to produce vinegar having a characteristic flavor. All vinegar having a certain per cent of solids is liable to deterioration through the agency of harmful bacteria hence storage in cool places is recommended for such as malt and cider vinegars.

- Edward Wiley Duckwall, Canning and Preserving of Food Products with Bacteriological Technique (1905) p. 127.

- Raw cultured vegetables have been around for thousands of years... Rich in lactobacilli and enzymes, alkaline-forming, and loaded with vitamins, they are an ideal food that can and should be consumed with every meal.

Since cultured foods are an excellent source of vitamin C, Dutch seamen used to carry them to prevent scurvy. For centuries, the Chinese have cultured cabbage each fall to ensure a source of greens through the winter... Cultured vegetables are a favorite food of the long-lived Hunzas. ...it's the active cultures of friendly bacteria (lactobacilli) inside [yogurt] that are responsible for good health. Similarly, the enzymes and the high lactic acid in raw cultured vegetables promote wellness and longevity.- Donna Gates, Linda Schatz, The Body Ecology Diet: Recovering Your Health and Rebuilding Your Immunity (1996)

- Gay-Lussac found that food treated by Appert's method was quite stable, but as soon as it was exposed to air, fermentation and/or putrefaction set in. Further experiments enabled Gay-Lussac to prove that air was the causative agent, and that if liquid foods were actually boiled, and then exposed to air, then the onset of the two processes was delayed. He also found that if brewer's yeast was heated, it was incapable of initiating fermentations.

- Ian Spencer Hornsey, A History of Beer and Brewing (2003)

- [K]oji [is] the Japanese manifestation of qu, also traditionally a mixed culture but today typically known as a single a strain of fungus, Aspergillus oryzae. Before I started growing koji, I would never have believed it possible to fall in love with a mold. ...Koji itself is not generally eaten as a food (although it is delicious). Koji is the first step toward many elaborately processed foods and beverages. ...try it at least once using a starter culture so you can experience the unique aroma of fresh growing koji, because recognizing that unique smell is the most straightforward way you have to gauge whether you have the right mold growing if you try starting koji spontaneously using corn husks.

- Sandor Katz, The Art of Fermentation (2012)

- Searching investigations into the chemical activity of the different species of acetic acid bacteria would be not only opportune in the interests of science, but also highly important to the practice of the vinegar industry. In this business the employment of selected pure culture ferments is not yet regarded as a fundamental rule, everything being still left to the mercy of chance.

...there are two different methods of making vinegar. In one of them wine forms the raw material, this method being known as the Orleans process... There (as elsewhere) the work is still performed in the same manner as it was centuries ago as follows:—A number of oaken casks, each of a capacity of some 55 gallons, are arranged in rows in a chamber maintained at a constant temperature of 18° to 22° C [64° to 71° F]. In the upper part of the front end (head) of each cask a circular aperture (a few cm in width) is provided, through which the cask can be filled or emptied, and which is generally kept closed, whilst near it is a very small hole (vent) always left open for the admission of air. In normal work each cask is about half full. Before setting a new cask in work, it is scalded out several times with steam or hot water, in order to extract the sap from the wood, and is then "soured" by impregnating it with good, boiling-hot vinegar. About 1 hl. (22 gallons) of good, clear vinegar and 2 l. (0.44 gallons) of wine are then placed in the cask, another 3 l. of wine being added at the end of eight days, 4 to 5 l. more after the lapse of another week, and so on until the cask contains 180-200 l. (40 to 44 gallons). Then, for the first time, vinegar is drawn from the cask, and in such quantity that about 22 gallons are left behind in the vessel. From that time the cask "mother" is in continuous use, 10 litres (2.2 gallons) of vinegar being withdrawn every week and replaced by an equal quantity of wine. The "mother" casks may remain in work during six or eight years without interruption, but at the end of this period they will contain such a considerable accumulation of deposited yeast, tarter and mother of vinegar, as to necessitate their being emptied and cleansed. A skin, known as vinegar flowers or mother of vinegar, and composed of acetic acid bacteria, develops on the surface of the liquid, and the manner and luxuriance of its growth enables the operator to judge the progress of the fermentation. However, at the outset the growth proceeds very slowly, since the wine employed mostly contains but very few of these bacteria. Consequently an opportunity is afforded for the development of rapid-growing injurious organisms, chiefly certain budding fungi, which consume the acetic acid. The aerobic "vinegar eels" also make their appearance.- Franz Lafar, Technical Mycology; the Utilization of Micro-organisms in the Arts and Manufactures (1898) Vol. I Schizomycetic Fermentation. pp. 397-398.

- If a number of flasks be charged with a clear nutrient solution, of a kind favourable to the growth of yeast and containing a fermentable sugar, and each of them be inoculated with a trace of a pure culture of different yeasts, such as are used in brewing, distillery work, vinification, &c., the cultures being then kept at room temperature for a couple of days, it will be found that cell reproduction and fermentation—manifested by the appearance of turbidity and gas bubbles—will occur in all. It will thereafter soon be possible to separate the flasks into two groups, according to the appearance presented. In the one group the yeast crop developed from the sowing will remain almost entirely within the liquid throughout the entire period of fermentation, and mostly at the bottom even from the start. Yeasts of this kind are termed bottom yeasts, and excite bottom-fermentation, the yeast crop being sedimental.

In the other group the fermentation is very brisk and attended with the formation of large quantities of froth (head); and in the earlier stages a larger or smaller number of the new cells are raised to the surface by the ascending bubbles of gas, and remain there—provided the vessel be high enough to prevent frothing over—until fermentation is terminated and the froth breaks up, whereupon they sink down to the bottom of the liquid and increase the sedimental deposit. This kind of fermentation is termed top-fermentation, and the yeasts producing it are called top-fermentation yeasts. Typical examples of bottom-fermentation yeasts are afforded by the Munich lager-beer yeasts.- Franz Lafar, Technical Mycology; the Utilization of Micro-organisms in the Arts and Manufactures (1903) Vol II. Eumycetic Fermentation, Part I, p. 113

- The present status of surgery depends, primarily, upon the efforts of chemists, especially those interested in wine and beer production, to determine why milk turns sour, grape juice becomes wine, wine vinegar, and vinegar "a foul, insipid fluid," without the addition of any chemical reagent.

The difficulty in explaining this change was due to the fact that no chemical formula could be evolved which fully represented the equation. It was easy to write a formula that expressed in definite terms the change that had resulted in a given case, but it was impossible to explain what had set the process in motion. Why was it that milk would change from sweet to sour, showing that the milk sugar it contained had become lactic acid, while a solution of pure milk sugar in pure water absolutely refused to undergo the same process? It became evident that there was something else inherent to the fermenting process that set it in motion. ...

The problem was gradually clearing up as far back as Von Helmont... who first showed that the gas eliminated during fermentation was different from the air and identical with that formed by the combustion of charcoal and the calcination of limestone. ...

Stahl... was the first to discover that vinous fermentation and putrefaction belong to the same class of phenomena... Leuwenhoek... in 1680 found, with the imperfect microscopes in use at that time, that yeast consisted of minute globular or ovoid particles... It took until 1836 for Schwann and Caignard-Latour, acting independently of one another, to prove that Leuwenhoek's globules were membranous bags, exhibiting the characteristics of vegetable cells and increasing and multiplying rapidly in the same way when brought under proper conditions. It had already been recognized that the yeast increased in vinous fermentation, and therefore it was natural that they should conclude that yeast was a plant, and that as it grew it in some unexplained way set up the chemical change. ...

Schroeder and Von Dusch (1854) published the fact that a cotton plug prevented the something in the air that set fermentation and putrefaction in motion from coming in contact with the solutions or solids that otherwise would become proper media for the setting up of the processes. In 1860, and the next few succeeding years, Pasteur settled the whole question by his masterly review of the field, and his own remarkable series of experiments. Following this came Lister's appreciation of the results of these experiments in their application to surgery...- Samuel Lloyd, "Aseptic Surgery its Application to Private Practice" in The Medical and Surgical Reporter (1896) Vol. 74, pp. 328-329.

- Rejuvelac is a rich, nutrient-dense living water that's fermented from sprouted grains or seeds. ...rejuvelac not only costs pennies on the dollar but ranks in superiority in terms of probiotic quality and quantity. ...It takes about five days to make and is suprisingly easy ...The seeds or grains must be raw or they will not sprout. ...You can use rejuvelac in place of any recipe calling for water. ...Rejuvelac is also a [DIY] starter used in fermented creams, yogurts and cheeses [to include those made from nuts and seeds]. Stir in some juice, honey, and ice cubes for a delicious beverage. ...soak ...seeds or grains ...covered in water for eight hours or overnight. Buckwheat or smaller seeds, can take as little as two hours. ...Drain off the water. Give the grains a good rinse... twice a day (or more)... cover the sprouts with a breathable cloth. ...out of direct sunlight. Tilt the jar... and let the water drain out. ...After the berries have sprouted, give them a final rinse and fill... with water... approximately 4 to 6 times more water than sprouts. ...Let it sit thirty-six to forty eight hours [covered with a breathable cloth]. Less time... if the weather is warm... more if... cool. ...A slightly sour and fizzy taste should be the result. (If it tastes like it's gone bad, discard... you can water the plants with it—and begin again.)

- Jennifer Mac, Detox Delish: Your Guide to Clean Eating (1982)

- During lactic acid fermentation... a characteristic fermentative yeast flora develops in the liquid... When the sugar is used up and the pH has dropped because of lactic acid production by the lactic acid bacteria, a secondary, oxidative yeast flora develops on the surface of the liquid in the form of a thick, folded layer of yeast.

- Herman Jan Phaff, Herman Phaff, Martin Wesley Miller, Emil Marcel Mrak, The Life of Yeasts: Their Nature, Activity, Ecology, and Relation to Mankind (1966)

- If milk is produced under clean conditions, it is not likely to have a disagreeable odor or taste at any time, even when it is sour; rather the taste is agreeable like that of good butter milk. The curd is perfectly homogeneous, showing no holes or rents, due to the development of gas, and there is but little tendency for the whey to be expressed from the curd. This type of fermentation is largely produced by the group of bacteria to which has been given the name, Bacillus lactis acidi.

The main by-product of this group of bacteria is lactic acid; small amounts of acetic acid and alcohol, with traces of other compounds, are also formed. The agreeable odor and to some extent the flavor of milk fermented by these bacteria is due to other by-products than lactic acid, for this has no odor and only a sour taste. The acid fermentation of milk is often called the lactic acid fermentation. In reality only the fermentation produced by the desirable group in which lactic acid is the most evident by-product should be thus called.- H.L. Russell, E.G. Hastings, Outlines of Dairy Bacteriology: A Concise Manual for the Use of Students in Dairying (1914) 10th edition, pp. 86-87.

- Undesirable acid-forming bacteria... capable of forming substances that impart to milk an offensive odor and a disagreeable taste not infrequently appear instead of the desirable group. Instead of producing from the sugar of milk large quantities of lactic acid, these types generate other acids, such as acetic and formic, which impart a sharp taste to the milk. Besides the acids the bacteria of this group form gases from the sugar of the milk. Some produce small amounts of gas; others so much that the curd will be spongy and will float on the surface of the whey. The fermentation caused by them is often called a "gassy fermentation" and is dreaded by butter and cheese makers since the gas is indicative of bad flavors... Gas may also be produced in other types of fermentations...

This class of bacteria enters the milk with the dust, dirt, and manure, in which materials they are especially abundant. No spores are formed; hence they are easily killed by heating the milk. They grow both in the presence and in the absence of free oxygen. High temperatures favor their growth, most rapid development taking place at 100° to 103° F. ...The normal souring of milk is due to a mixture of these two groups [Bacillus lactis acidi and the undesirable acid-forms] of bacteria. The relative proportions existing between the two in any sample of milk is dependent on a number of factors, most important of which is the degree of cleanliness...- H.L. Russell, E.G. Hastings, Outlines of Dairy Bacteriology: A Concise Manual for the Use of Students in Dairying (1914) 10th edition, pp. 90-91.

- Basically, the preparation method of soy sauce koji involves washing and soaking the rice grains overnight, steaming the well-drained soaked rice for about 60 minutes, rapidly cooling and breaking the lumps of rice, mixing uniformly the ash and starter, distributing in trays and incubating in a special room for about 5 days with in-between stirring of the mixture on the second day and the third day. The molded rice is thoroughly dried, packaged, and stored in cold room with low humidity. Strict observation of aseptic conditions is required at every step of the preparation.

- Priscilla Chinte-Sanchez, Philippine Fermented Foods: Principles and Technology (2008)

- [T]he French Academy of Sciences in 1779 had posted a prize of one kilogram of gold for a solution of the mystery of fermentation. Unfortunately, the offer had to be withdrawn in 1793... but Cagniard-Latour's inquisitive spirit was undaunted by the cancellation... He described the features of yeast cells, classified them as plants, observed the process of budding and noted the differences in shape between wine- and beer-yeasts. He also found the multiplication of the cells required nitrogenous material in addition to fermentable carbohydrate. ...Unfortunately, however, he reverted to his research interest in physics.

- Fritz Shelenk, "Early Research on Fermentation—A Story of Missed Opportunities" in New Beer in an Old Bottle: Eduard Buchner and the Growth of Biochemical Knowledge (1997) ed. Athel Cornish-Bawden

- The tempeh is simply mixed with cooked, dehulled soybeans; the mycelium continues its growth without the... spores. ...however, [it] generally has a lightly weaker mycelium and the incubation time is a little longer than... sporulated methods. And... there are always some unwanted bacteria in the original tempeh. If you are careless and/or the humidity is high, their numbers will increase with each generation until eventually they prevail, preventing the formation of good tempeh. However, by being clean and careful, we have had no trouble in keeping this starter going for more than 12 generations...

- Wiliam Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi, The Book of Tempeh (1979)

- Miso, or “fermented soybean paste,”... is an all-purpose high-protein seasoning, which has no counterpart among Western foods or seasonings. Made from soybeans, rice or barley, and salt... [i]t comes in a wide range of warm, earthy colors... Each miso has its own distinctive flavor and aroma... Miso’s range of flavors and colors, textures and aromas, is at least as varied as that of the world’s fine wines or cheeses.

- Wiliam Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi, History of Miso (2009) Introduction

- Koji is a culture prepared by growing... Aspergillus oryzae... mold on cooked grains and/or soybeans in a warm, humid place. Koji serves as a source of enzymes that break down (or hydrolyze / digest / split) natural plant constituents into simpler compounds when making miso, soy sauce, sake, amazake, and other fermented foods. Its fragrant white... mycelium... has a delightful aroma resembling that of mushrooms. ...Koji is written with the exact same character in China and Japan. ...In China this character is romanized as qu... Koji was invented in China at least three centuries before the Christian era.

- William Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi, History of Koji - Grains And/or Soybeans Enrobed with a Mold Culture (300 BCE To 2012) (2012) Introduction

- Koji usually serves as the basis of secondary fermentation, in which its enzymes help to hydrolyze (break down or digest or split) basic nutrients. ...amylase ...digests carbohydrates ...protease breaks down proteins, and ...lipase ...digests lipids (fats). Rice... barley... and soybean koji are used to make three different types of miso. Koji for Japanese soy sauce is made from a mixture of roasted wheat and defatted soybean meal; this koji is dark-green in color. Whole soybean koji is used to make traditional Chinese soy sauce and fermented black soy beans (also known as... Douchi ...etc.). Rice koji is used to make Japanese amazake... and sake... Koji is to sake as malt is to beer. Each saccharifies the starch... so that... sugars can be fermented to alcohol by yeasts.

- William Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi, History of Koji - Grains And/or Soybeans Enrobed with a Mold Culture (300 BCE To 2012) (2012) Introduction

- Sufu (Chinese soy cheese) and stinky tofu (chaotofu) are block-type fermented soy foods. In the manufacture... sufu utilizes mainly mold(s), whereas stinky tofu utilizes mainly bacteria. Molds multiply under aerobic condition and produce amylase, protease, and other hydrolases

- Der-Feng Teng, Chyi-Shen Lin, Pao-Chuan Hsieh, "Fermented Tofu: Sufu and Stinky Tofu," Handbook of Food and Beverage Fermentation Technology (2004) ed., Y.H. Hui., Meunier-Goddik, Josephsen, Nip & Stanfield.

See also

editExternal links

edit- Fermented Cereals: A Global Perspective from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- YouTube videos:

- Fermenting Vegetables with Sandor Katz @sandorkraut

- Introduction to Vegetable Fermentation @Living Web Farms

- Lacto-Fermentation: The Secret of Healing with Katalin Brown @Richters Herbs

- Preserving Food Without Refrigeration with Kelley Wilkinson @Living Web Farm