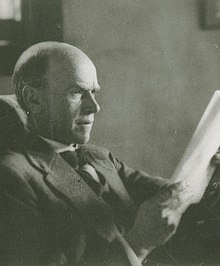

Elton Mayo

Australian psychologist and sociologist

George Elton Mayo (26 December 1880 – 7 September 1949) was an Australian born psychologist, industrial researcher, and organizational theorist, who helped to lay the foundation for the human relations movement.

Quotes

edit- What social and industrial research has not sufficiently realised as yet is that... minor irrationalities of the “average normal” person are cumulative in their effect. They may not cause “breakdown” in the individual but they do cause “breakdown” in the industry.

- Elton Mayo, “Irrationalty and Revery”, Journal of Personnel Research, March 1933, p.482; Cited in: Ionescu, G.G., & A.L. Negrusa. "Elton Mayo, an Enthusiastical Managerial Philosopher." Revista de Management Comparat International 14.5 (2013): 671.

- One friend, one person who is truly understanding, who takes the trouble to listen to us as we consider our problem, can change our whole outlook on the world.

- Elton Mayo, cited in: Edward William Bok (1947), Ladies' Home Journal.Vol. 64, p. 246

Democracy and freedom. 1919

editElton Mayo (1919), Democracy and freedom, An Essay in Social Logic. Macmillan & co., ltd.

- Viewed from the standpoint of social science, society is composed of individuals organized in occupational groups, each group fulfilling some function of the society. Taking this fact into account, psychology – the science of human nature and human consciousness – is able to make at least one general assertion as to the form a given society must take if it is to persist as a society. It must be possible for the individual as he works to see that his work is socially necessary; he must be able to see beyond his group to the society.

- p. 37

- The recent growth of interest in political matters in Australia is by no means a sign of social health.

- p. 43; Cited in: John Cunningham Wood, Michael C. Wood (eds). George Elton Mayo: Critical Evaluations in Business and Management, Volume 1. 2004, p. 78

- Revolution or civil war is the only outcome of the present irreconcilable attitude of Australian political parties. The methods of "democracy," far from providing a means of solving the industrial problem, have proved entirely inadequate to the task. Political organization has been mistaken for political education; the party system has accentuated and added to our industrial difficulties. Democracy has done nothing to help society to unanimity, nothing to aid the individual to a sense of social function.

- p. 44; Cited in: Wood & Wood (2004, 78).

- So long as commerce specializes in business methods which take no account of human nature and social motives, so long may we expect strikes and sabotage to be the ordinary accompaniment of industry. Sabotage is essentially a protest of the human spirit against dull mechanism. And the emphasis which democracy places upon political methods tends to transform mere sporadic acts of sabotage into an organized conspiracy against society.

- p. 56

The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilisation, (1933)

editElton Mayo. The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilisation, (1933/1960); online here

- The human aspect of industry has changed very considerably in the last fifty years. The nature and range of these changes are still partly unknown to us, but the question of their significance is no longer in dispute. Whereas the human problems of industry were regarded until recently as lying within the strict province of the specialist, it is now beginning to be realized that a clear statement of such problems in particular situations is necessary to the effective thinking of every business administrator and every economic expert.

- p. 1, Chapter 1: Fatigue; Lead paragraph

- In the nineteenth century there was an iU-founded hope that some species of political remedy for industrial ills might be discovered; this hope has passed. There have been very considerable political changes, both generally and also in particular national systems, since the end of the war in 1918. But the human problems of industrial organization remain identical for Moscow, London, Rome, Paris, and New York. As ever in human affairs, we are struggling against our own ignorance and not against the machinations of a political adversary.

- p. 1, Chapter 1: Fatigue

- Acting in collaboration with the National Research Council, the Western Electric Company had for three years been engaged upon an attempt to assess the effect of illumination upon the worker and his work.

- p. 55, chapter 3: The Hawthorne experiment Western Electric Company

- The history of the twelve-week return to the so-called original conditions of work is soon told. The daily and weekly output rose to a point higher than at any other time and in the whole period "there was no downward trend." At the end of twelve weeks, in period thirteen, the group returned, as had been arranged, to the conditions of period seven with the sole difference that whereas the Company continued to supply coffee or other beverage for the mid-morning lunch, the girls now provided their own food. This arrangement lasted for thirty-one weeks—much longer than any previous change. Whereas in period twelve the group's output had exceeded that of all the other performances, in period thirteen, with rest-pauses and refreshment restored, their output rose once again to even greater heights

- p. 65, chapter 3: The Hawthorne experiment Western Electric Company

- It had become clear that the itemized changes experimentally imposed, although they could perhaps be used to account for minor differences between one period and another, yet could not be used to explain the major change - the continually increasing production. This steady increase as represented by all the contemporary records seemed to ignore the experimental changes in its upward development.

- p. 65, chapter 3: The Hawthorne experiment Western Electric Company

- Defeat takes the form of ultimate disillusion — a disgust with the "futility of endless pursuit."

- p. 125

- The problem is not that of the sickness of an acquisitive society; it is that of the acquisitiveness of a sick society.

- p. 147

The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilisation, 1945

editElton Mayo. The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilisation. 1945/2014

- Little of the old establishment survives in modern industry: the emphasis is upon change and adaptability; the rate of change mounts to an increasing tempo. We have in fact passed beyond that stage of human organisation in which effective communication and collaboration were secured by established routines of relationship. For this change, physico-chemical and technical development are responsible. It is no longer possible for an industrial society to assume that the technical processes of manufacture will exist unchanged for long in any type of work. On the contrary, every industry is constantly seeking to change, not only its methods, but the very materials it uses ; this development has been stimulated by the war.

- p. 13; Partly cited in: Lyndall Urwick & Edward Brech (1949). The Making Of Scientific Management Volume III, p. 216

- If our social skills (that is, our ability to secure co-operation between people) had advanced step by step with our technical skills, there would not have been another European War.

- p. 30 (in 2014 edition); Cited in: Urwick & Brech (1949, 215)

- The statements of academic psychology often seem to imply that logical thinking is a continuous function of the mature person — that the sufficiently normal infant develops from syncretism and non-logic to logic and skilled performance. Such a description seems to be supported by much of the work of Piaget, of Claparede, and, with respect to the primitive, by Levy-Bruhl. If one examines the facts with care, either in industry or in clinic, one finds immediately that this implication, so flattering to the civilized adult, possesses only a modicum of truth. Indeed, one may go further and say that it is positively misleading.

- p. 42; Partly cited in Urwick & Brech (1949, 216)

- Management, in any continuously successful plant, is not related to single workers but always to working groups. In every department that continues to operate, the workers have whether aware of it or not formed themselves into a group with appropriate customs, duties, routines, even rituals ; and management succeeds (or fails) in proportion as it is accepted without reservation by the group as authority and leader.

- p. 81-82

- The difference between a good observer and one who is not good is that the former is quick to take a hint from the facts, from his early efforts to develop skill in handling them, and quick to acknowledge the need to revise or alter the conceptual framework of his thinking, The other — the poor observer — continues dogmatically onward with his original thesis, lost in a maze of correlations, long after the facts have shrieked in protest against the interpretation put upon them.

- p. 116; Cited in Supervisory Management, (1963), Vol. 8, p. 58

Quotes about Elton Mayo

edit- In the 1920s Elton Mayo, a professor of Industrial Management at Harvard Business School, and his protégé Fritz J. Roethlisberger led a landmark study of worker behavior at Western Electric, the manufacturing arm of AT&T. Unprecedented in scale and scope, the nine-year study took place at the massive Hawthorne Works plant outside of Chicago and generated a mountain of documents, from hourly performance charts to interviews with thousands of employees.

- "The Human Relations Movement: Harvard Business School and the Hawthorne Experiments (1924-1933)," at library.hbs.edu, 2012