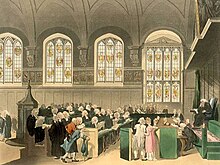

Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid the slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the administration of the estates of lunatics and the guardianship of infants. Its initial role was somewhat different, however; as an extension of the Lord Chancellor's role as Keeper of the King's Conscience, the Court was an administrative body primarily concerned with conscientious law. Thus the Court of Chancery had a far greater remit than the common law courts, whose decisions it had the jurisdiction to overrule for much of its existence, and was far more flexible. Until the 19th century, the Court of Chancery was able to apply a far wider range of remedies than the common law courts, such as specific performance and injunctions, and also had some power to grant damages in special circumstances. With the shift of the Exchequer of Pleas towards a common law court, the Chancery was the only equitable body in the English legal system.

Sourced

edit- This is the Court of Chancery, which has its decaying houses and its blighted lands in every shire, which has its worn-out lunatic in every madhouse and its dead in every churchyard, which has its ruined suitor with his slipshod heels and threadbare dress borrowing and begging through the round of every man's acquaintance, which gives to monied might the means abundantly of wearying out the right, which so exhausts finances, patience, courage, hope, so overthrows the brain and breaks the heart, that there is not an honourable man among its practitioners who would not give--who does not often give--the warning, "Suffer any wrong that can be done you rather than come here!"

- Charles Dickens, Bleak House (1852-1853), Ch. 1.

The Dictionary of Legal Quotations (1904)

edit- Quotes reported in James William Norton-Kyshe, The Dictionary of Legal Quotations (1904), p. 23-25.

- I hope the Chancery will not repeal an Act of Parliament. Waste in the house is waste in the curtilage; and waste in the hall is waste in the whole house.

- Hale, C.J., Cole v. Forth (1672), 1 Mod. Rep. 95.

- I do not think it is the business of the Court of Chancery to inquire into motives.

- Sir W. M. James, L.J., Denny v. Hancock (1870), L. R. 6 Ap. Ca. 10.

- Chancery is ordained to supply the law, and not to subvert the law.

- Lord Bacon, Bac. Speech, 4 ; Bac. Works, 488.

- In Chancery, every particular case stands upon its own circumstances, and although the common law will not decree against the general rule of law, yet Chancery doth, so as the example introduce not a general mischief. Every matter, therefore, that happens inconsistent with the design of the legislator, or is contrary to natural justice, may find relief here. For no man can be obliged to anything contrary to the law of nature ; and indeed no man in his senses can be presumed willing to oblige another to it.

- 1 Fonbl. Eq. B. 1, c. 1, § 3; Story, Eq. J. 10.

- It is surely desirable that the rules of this Court should be in accordance with the ordinary feelings of justice of mankind.

- Sir W. M. James, L.J., Pilcher v. Rawlins (1872), L. R. 7 C. Ap. Ca. 273.

- It is not agreeable to any man to be a defendant to an adverse Chancery suit, and I should be very sorry to sanction any principle which might lead to an increase in the number of defendants, and to the multiplication of litigant parties.

- Sir R. Matins, V.-C, Clark v. Lord Rivers (1867), L. R. 5 Eq. Ca. 96.

- The Court of Chancery is not a Court of Record, and a Judge in Chancery is not the keeper of the records of his own Court.

- Sir G. Jessel, M.R., In re Berdan's Patent (1875), L. R. 20 Eq. Ca. 347.

- Born and bred, so to say, in Chancery, I have a strong leaning towards the rule of the Court of Chancery, of requiring full discovery.

- Kekewich, J., Ashworth v. Roberts (1890), L. J. Rep. (N. S.) 60 C. D. 28.

- This Court is not a Court of penal jurisdiction. It compels restitution of property unconscientiously withheld; it gives full compensation for any loss or damage through failure of some equitable duty ; but it has no power of punishing any one.

- Sir W. M. James, L.J., Vyse v. Foster (1872), L. R. 8 Ch. Ap. Ca. 333.

- In the Court of Chancery, I think we are obliged to cut the knot as to the question of time, by naming some time.

- Lord Cranworth, Smith v. Kay (1859), 7 H. L. Cas. 772.

- This Court is not, as I have often said, a Court of conscience, but a Court of Law.

- Jessel, M.R., In re National Funds Assurance Co. (1878), L. R. 10 C. D. 128.

- The cause why there is a Chancery is, for that men's actions are so divers and infinite, that it is impossible to make any general law, which may aptly meet with every particular act, and not fail in some circumstances.

- Lord Ellesmere, Earl of Oxford's Case (1661), Rep. in Ch. 4.

- The Court of Chancery never decrees that shall be evidence, which in its nature is not evidence.

- Richard Aston, J., Ludlam on the Demise of Hunt (1773), Lofft. 364.

- For us to reverse the judgment of a Lord Chancellor would require a tremendous case—a case of a clear error.

- James, L.J., Wheeldon v. Burrows (1879), 12 Ch. D. 47; per Thesiger, L.J., 48 L. J. Ch. 859. Also per Cotton, L.J., in In re Watts, Cornford v. Elliott (1885), 29 Ch. D. 953; 55 L. J. Ch. 334.

- I may say I do not consider the decision of a Lord Chancellor is absolutely binding upon us, because every Lord Chancellor's decision was liable to be reheard not only by himself but by his successor, and there are known instances of it. When I was sitting with Lord Justice Mellish we did rehear decisions of Lord Chancellor Selborne. There is always this to be considered, that it is the decision, no doubt, of a superior Court of Appeal; but it is always qualified by this, that according to the old practice of the Court of Chancery it was liable to be reheard.

- James, L.J., Ashworth v. Munn (1880), L. R. 15 C. D. 377. See also per Jessel, M.R., in Henty v. Wrey (1882), L. R. 21 C. D. 346.

- I think the Lord Chancellor, wherever he is sitting and whatever cases he is trying, is still Lord Chancellor, and that his decision is binding on me.

- Fry, L.J., Ex parte Vicar of St. Mary, Wigton (1881), L. ft. 18 C. D. 648.