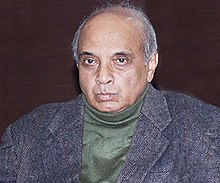

Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti

Indian archaeologist

(Redirected from Chakrabarti, D. K.)

Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti (born 27 April 1941) is a noted Indian archaeologist and professor of South Asian archaeology at Cambridge University. He is known for his studies on the early use of iron in India and the archaeology of Eastern India.

| This article about a historian is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |

Quotes

edit- “In several Indian universities that I can think of – Delhi University, for instance -- students were positively discouraged to read those ‘nationalist’ writings”

- D. K. Chakrabarti, Nationalism in the Study of Ancient Indian History (Aryan Books International, Delhi). and quoted in [1]

- The communists had a free run so far, their opponents being no match in the psychological warfare launched by the communists. These opponents have had the control of the ICHR uninterruptedly since 2014 but they have basically been unable to neutralize the communist lobby in Indian historical studies. They are not motivated enough and focused enough. They regrettably are not even professional enough to realize where the communists have to be hurt to their disadvantage.

- D. K. Chakrabarti, Nationalism in the Study of Ancient Indian History (Aryan Books International, Delhi). and quoted in [2]

- After Independence . . . [Indians]—especially those from the ‘‘established’’ families—were no longer apprehensive of choosing History as an academic career . . . To join the mainstream, the historians could do a number of things: expound the ruling political philosophy of the day, develop the art of sycophancy to near- perfection or develop contacts with the elite in bureaucracy, army, politics and business. If one had already belonged to this elite by virtue of birth, so much the better. For the truly successful in this endeavor, the rewards were many, one of them being the easy availability of ‘foreign’ scholarships/fellowships, grants, etc. not merely for themselves but also for their protégés and the progeny. On the other hand, with the emergence of some specialist centers in the field of South Asian social sciences in the ‘foreign’ universities, there was no lack of people with different kinds of academic and not-so-academic interest in South Asian history in those places too, and the more clever and successful of them soon developed a tacit patron-client relationship with their Indian counterparts, at least in the major Indian universities and other centers of learning. In some cases, ‘institutes’ or ‘cultural centers’ of foreign agencies were set up in Indian metropolises themselves, drawing a large crowd of Indians in search of short-term grants or fellowships, invitations to conferences, or even plain free drinks.

- Antonio de Nicolas, Krishnan Ramaswamy, and Aditi Banerjee (eds.) (2007), Invading the Sacred: An Analysis Of Hinduism Studies In America (Publisher: Rupa & Co., p. 113

- If one goes through the archeological literature on Egypt and Mesopotamia, [especially] the areas where Western scholarship has been paramount since the beginning of archeological research in those areas, one notes that the contribution made by the native Egyptian and Iraqi archeologists is completely ignored in that literature. The Bronze Age past of Egypt, Mesopotamia and the intervening region are completely appropriated by the Western scholarship. Also, when Western archeologists write on Pakistani archeology, they seldom mention the contribution made by the Pakistani archeologists themselves. There are exceptions, but they are very rare. After Independence, the Archeological Survey of India pursued a policy of relative isolation, which enabled archeology as a subject to develop in the country and helped Indian archeologists to find their feet. The policy seems to be changing now. . . . There is a great deal of arrogance and sense of superiority in that segment of the first world archeology, which specializes in the third world. Unless this segment of the first world archeology changes its way and attitude, it should be treated with a great deal of caution in the third world.

- quoted from Malhotra, R., Nīlakantan, A. (2011). Breaking India: Western interventions in Dravidian and Dalit faultlines

- Chakrabarti (1997) has nothing but scorn for the Indian intellectual elites who "fail to see the need of going beyond the dimensions of colonial Indology, because these dimensions suit them fine and keep them in power" (213). In his view, "as the Indian historians became increasingly concerned with the large num- ber of grants, scholarships, fellowships and even occasional jobs to be won in Western universities, there was a scramble for new respectability to be gained by toeing the Western line of thinking about India and Indian history" (2). The result is that "institutions on the national level have to be 'captured' and filled up with stooges of various kinds," and "making the right kind of political noises is important for historians" (212). Accord- ingly, "after independence, when the Indian ruling class modeled itself on its departed counterpart, any emphasis on the 'glories of ancient India' came to be viewed as an act of Hindu fundamentalism" (2).19

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. ch 13

- Thus, anti-Aryan invasionist scholarship, in its turn, is stereotyped as being subser- vient to secular, Marxist ideology. The most maligned figureheads are precisely those who have most publicly opposed the Indigenous Aryan position, particularly R. S. Sharma, "a 'Marxist' historian of Indian variety who became a pillar of the historical establishment in his country," and Romila Thapar, "another 'mainstream' historian who harangued us on the importance of looking at ancient Indian history and archaeology through the prism of anthropological and sociological ideas, without telling us if such exercises by themselves would lead to a better historical understanding of ancient In- dia" (Chakrabarti 1997, 164).

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. ch 13

- Chakrabarti (1997) is not at all reticent in stating: It is the interplay of race, language and culture which has provided the most strong plank of the understanding of ancient India by the Westerns and the Indians alike. This plank was laid down at the height of Western political hegemony over India, and the fact that this still has been left in its place speaks a volume for the post-1947 pattern of the reten- tion of Western dominance in various forms. . . . We believe that unless this major plank of colonial Indology is dismantled and taken out, it is unlikely that there will be a non- sectarian and multi-lineal perspective of the ancient Indian past which will try to under- stand the history of the subcontinent in its own terms. (53)

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. ch 13

- Chakrabarti (1997) is forcefully pronouncing in print what many Indian intellectuals will reveal in private conversations: We have no hesitation in asserting that the "Nigger Question" is in various forms still very much a part of the Indological scene. Right from patronizing comments on "Babu English" to wry remarks on Indian nationalism for refusing to accept the idea of Greek and other extraneous origins of some of the crucial traits of Indian culture, the Western Indological literature has been consistent in viewing the general Indian scholarship in the matter as an inferior product. . . . Some Indians' refusal to acknowledge the veracity of Aryan invasion of India is interpreted by Western Indologists as misdirected symp- toms of "north Indian nationalism." (114)

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. ch 13

- Chakrabarti (1997) comments: Rumblings against some of the premises of Western Indology have been heard from time to time, but such rumblings have generally emerged in uninfluential quarters, and in the context of Indian historical studies this would mean people without control of the major national historical organizations, i.e., people who can easily be fobbed off as "fundamen- talists" of some kind, mere dhotiwalas of no intellectual consequence. (3)

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. ch 13

- Regarding the pastoral nature of the Indo-Aryans, Chakrabarti (1986) adds a further observation that "the inconvenient references to agriculture in the Rigveda are treated as later additions. The scholars who do this forget that effective agriculture is very old in the subcontinent, and surely no text supposedly dating from 1500 B.C. could depict a predominantly pastoral society anywhere in the subcontinent. Something must be wrong with the general understanding of this text" (Chakrabarti 1986, 76). In other words, if the Indo-Aryans were pastoralists, they must have always coexisted with agriculturists in India since agriculture predates the assumed date for their arrival by millennia. There could never have been a purely pastoral economic culture.

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. chapter 9

- Dilip Chakrabarti's comments (1986) are of relevance here: "Archaeology must take the entire basic framework of the Aryan model into consideration. It should not be a question of underlining a particular set of archaeological data and arguing that these data conform to a particular section of the Vedic literary corpus without at all trying to determine how this hypothesis will affect the other sets of the contemporary archaeological data and the other sections of the Vedic literary corpus" (74).

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. chapter 10

- Chakrabarti (1977b) finds that they "may more satisfactorily be explained as nothing more than what they apparently are: isolated objects finding their way in through trade or some other medium of contact, not necessarily any population movement of historic magnitude" (31). He notes that prior to die artificial boundaries demarcated by the British, the southern part of the Oxus, eastern Iran, Afghanistan, and the Northwest of the subcontinent all constituted an area with significant economic and political interaction throughout the ages—a sphere of activity distinct from the Iranian heartland to the west and Gangetic India to the east. In such an economic and geopolitical zone, "any new significant cultural innovation in any one area between the Oxus and the Indus is likely to spread rapidly to the rest of this total area" (31). As far as he is concerned, "the archaeological data from the Indus system and the area to its west . . . which have been interpreted as different types of diffusion from a vague and undefined West Asia are no more than the indications of mutual contact between the geographical components of this interaction sphere" (35).

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. chapter 11

- Chakrabarti (1997b) believes such constraints have severely crippled the visualization of "protohistoric growth in inner India in its own terms, without any reference to the supposed multiple waves of people pouring in from the West" (35).

- in Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : the Indo-Aryan migration debate. Oxford University Press. chapter 11

Colonial Indology

edit- Chakrabarti, D. K., 1997. Colonial Indology: Sociopolitics of the Ancient Indian Past. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Mill’s contempt for ancient India extends to the other Asian civilizations as well and . . . much of Mill’s framework has survived in the colonial and post-colonial Indology. For instance, his idea that the history of ancient India, like the history of other barbarous nations, has been the history of mutually warring small states, only occasionally relieved by some larger political entities established by the will of some particularly ambitious and competent individuals has remained with us in various forms till today.

- This book explores some underlying theoretical premises of the Western study of ancient India, These premises developed in response to the colonial need to manipulate the Indians’ perception of their past. The need was felt most strongly from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, and an elaborate racist frame work, in which the interrelationship between race, language and culture was a key element, slowly emerged as an explanation of the ancient Indian historical universe. The measure of its success is obvious from the fact that the Indian nationalist historians left this framework unchallenged, preferring to dispute it only in some comparatively minor matters of detail, This book argues that this framework is still in place, and implicitly accepted not merely by Western Indologists but also by their Indian counterparts. The image of the ancient Indian past remains the same. The persistence of the old image is reflective of India’s relationship as a part of the Third World with the West and Western historical scholarship,

- Preface

- The academic scope of the present volume may be clearly stated at the outset, It begins by arguing that one of the underlying assump- tions of Western Indology is a feeling of superiority in relation to India, especially modern India and Indians. This feeling of superi- ority is expressed in various ways. On one level, there are recurrent attempts to link all fundamental changes in Indian society and history to Western intervention in some form. The image of ancient India which was foisted on Indians through hegemonic texts emanating from Western schools of Indology had in mind an India that was steeped in philosophical, religious and literary lores and unable to change herself without external influence, be it in the form of Alexander the Great, Roman ships carrying gold or the Governor-Generals of the British East India Company. On a different level, expressions of Western superiority can be more direct and encompass a wide range of forms: patronizing and/ or contemptuous reviews of Indian publications, allusions to per- sonal hardships while working in India, refusal to acknowledge Indians as “agents of knowledge”, or even blatant arrogance which makes one wonder if the civilized values of Western academia have not left its Indology mostly untouched.

- p. 1

- Historically, this should hardly cause any surprise. After all, Western Indology is an essential by-product of the process of the establishment of Western dominance in India. Racism—in this case a generic feeling of superiority in relation to the natives—was, quite logically, one of the major theoretical underpinnings of this process. Itis but natural that Western Indology should carry within it a lot of this feeling of superiority. We are not surprised by this.

- p. 1

- To join the main stream the historians could do a number of things: expound the ruling political philosophy of the day, develop the art of sycophancy to near-perfection or develop contacts with the elite in bureaucracy, army, politics and business. If one had already belonged to this elite by virtue of birth, so much the better.

- p. 7

- ...without bothering to find out if.. such blind fetishism did not sometimes lead to a theoretical position undermining the Indian national identity.

- To us, this is the first major racist elaboration of the ancient Indian history and culture in Western Indology, and all that we note here is that Mill’s contempt for ancient India extends to the other Asian civilizations as well and that much of Mill’s framework has survived in the colonial and post-colonial Indology. For instance, his idea that the history of ancient India, like the history of other barbarous nations, has been the history of mutually warring small states, only occasionally relieved by some larger political entities established by the will of some particularly ambitious and competent individuals has remained with us in various forms till today. His ideas that the Indian civilization never prospered except under foreign domination and that it was no doubt inferior to the Greek and Roman civilizations have been accepted almost as axioms by Western and neo-colonial Indian Indology...

- 94

- The way in which the evidence of pre-Sargonic contact of the Indus civilization with Mesopotamia has been pushed into the background while making its chronological assessment and the way in which the sporadic material from the Bactria-Margiana complex ... has been dated to make that related to the end-phase of this civilization may be considered singularly interesting and indicative of a great mental block suffered by some archaeologists to accept the obvious and admit of the possibility of a considerably earlier beginning of the Indus civilization and its much larger duration.

- 177

- We need not follow Spooner further in his exploration of the bylanes of Indology where anything goes.

- 193

- Indians would certainly try to understand the fact that for more than a hundred years in the late fourth, third and early second centuries BC, there was a state which controlled the entire natural geographical domain of south Asia. Not even the British controlled such a large area for such a long period. This fact should in any case be one of the answers to the notion that there have only been divisive tendencies in the political history of India.

- 206

About

edit- Chakrabarti himself served at Delhi University for a while, and was the target of Communist slander there. Editing A History of Ancient India in 2013, he found that major publishers refused, slated contributors withdrew etc.: “cancel culture”.

- Elst, K. A case of good nationalism: DK Chakrabarti on historiography (Pragyata, 5 February 2021)