California genocide

mass murder of the indigenous population of California due to violence, relocation and starvation as a result of the U.S. occupation of California

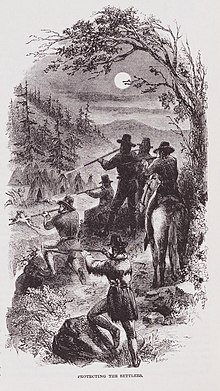

The California genocide was the genocide of the Indigenous peoples of California during the colonization of California. Between 1846 and 1873, across California, the indigenous population declined by approximately 70 percent. Murders by U.S. agents and white settlers were carried out through massacres, forced labor, biological warfare, and starvation.

~ Mickey Gemmill (Pit River)

Quotes

edit- Alphabetized by author

B

edit- Even as southern states seceded and the country careened toward civil war, Congress once again emphatically endorsed and generously financed California’s killing machine. The new act appropriated up to $400,000 to pay the expenses of the nine California militia campaigns that had killed at least 766 California Indians from 1854 through 1859. The euphemistically titled “Act for the payment of expenses incurred in the suppression of Indian hostilities in the State of California” rejuvenated state militia Indian-hunting operations even as outrage against such campaigns became public at local, state, and federal levels. Genocide in California becoming a national issue, and the US government would soon become even more directly involved.

F

edit- Genocide of indigenous peoples occurred in California... and its perpetrators were primarily miners and settlers who had recently arrived from the East... The Native population [was] about 100,000 in 1849, during the Gold Rush, and [fell] to about 30,000 in 1870. It subsequently reached a nadir of 15,000 to 25,000 during the decade 1890-1900.

- Margaret Fields, Genocide and the Indians of California (May 1993)

H

edit- I saw one of the squaws after she was dead; I think she died from a bullet; I think all the squaws were killed because they refused to go further. We took one boy into the valley [reservation], and the infants were put out of their misery, and a girl 10 years of age was killed for stubbornness.

- H.L. Hall, "Indian War Files of the California Archives" (1860)

J

edit- Leland Stanford himself passed legislation and recruited volunteers for US Army battalions that hunted and killed hundreds of Native Americans... The wealth and privilege we gain from attending Stanford were created by the sacrifices of previous generations, including the unpaid labor and genocide of California Indians.

- Berber Jin, "An Overdue Encounter with the Past," Stanford Politics, (2017)

L

edit- Serranus Hastings was expert in utilizing ‘externalities’ to shift to the State the substantial expenses of clearing his claimed lands and perpetuating a slave system predicated on terror, killings, rapes, and forced family separation which funneled into the slave camp known as the Nome Cult Farm, where one could eat only if one could work. That he was significantly responsible for genocidal atrocities against the native peoples of Round Valley is not in dispute.

- Paul Laurin, quoted in "Hastings Law balks at name change despite founder's role in genocide," SFGate, (2020)

N

edit- The extermination of the Yuki Indians of California’s Round Valley near Mendocino constitutes yet another story of the violent confrontation of settlers and native peoples. This relatively small tribe of 7,000 to 11,000 members on the eve of the settler inlux in the late 1850s was wiped out between 1856 and 1864. Genocidal killing and forced confinement to the reservation reduced the number of Yuki to 85 males and 215 women. The numbers continued to decline in the late nineteenth century as a result of starvation and sickness, as well as episodic fights with the settlers. The Round Valley Reservation still exists as the home of some 100 Yuki, plus a number of other California tribes. There are a handful of Yuki speakers still alive.

- Norman Naimark, Genocide: A World History (2017)

- On February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, ending the Mexican-American War and ceding California to the United States. Almost at the same time, on January 24, 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, in the Sierra foothills. The gold rush that followed brought some 300,000 people to California, both from the East Coast of the United States and from abroad. While the prospectors fanned out into the foothills, many of the newcomers settled in the boomtown of San Francisco. The city required much more food and housing, and local ranchers and settlers looked for new lands to graze their animals. Round Valley served as a perfect destination for the herdsmen, causing immediate conflicts with the Yuki, Round Valley’s inhabitants. The settlers and their herds of cows and horses trampled the traditional products of Yuki foraging. Indians were attacked and beaten by the settlers, who thought of them as “savages” at best and little more than animals at worse. The Yuki began to retaliate by killing the settlers’ cattle for food and driving off their horses. California was admitted to the Union as a state in 1850, and its new government decided to set aside a reservation in 1856 for the Yuki in the northern part of the valley as a way to avoid confrontation between the settlers and the Indians. Some 3,000 Indians moved to the reservation, while others scattered around the valley and into the woods to the north and east, merging, in some cases, with other tribes that lived in the region. For their sustenance, the Indians would return to the valley to hunt game or gather roots and acorns, only to be driven off by the settlers, who were increasingly aggressive in shooting the Yuki and kidnapping their women for sexual exploitation. As the settlers claimed property and fenced off their ranches, they also set out in posses to punish the Yuki for rustling. In response, the Yuki sometimes killed whites, though in much smaller numbers than their own losses.

- Norman Naimark, Genocide: A World History (2017)

- The Round Valley Wars turned overtly genocidal in 1859, when the governor of California, John Weller, authorized the formation of the so- called Eel River Rangers, headed up by the settler and noted “Indian killer” William S. Jarboe. Jarboe and his band of vigilantes had already been responsible for the murder of some sixty- three Yuki men, women, and children. He was then authorized by the governor to deal with the problem. His way of doing it, as he told his rangers, was: “Kill all the bucks they could find, and take the women and children prisoners." For Jarboe and his men, the Indians were less than human; they were vermin, who stole and concealed, hid and ran, not at all worthy opponents of the settlers. Some three hundred Indians were killed in Jarboe’s campaign; another three hundred were sent to the reservation. For his work, Jarboe presented a bill to the state of California for $11,143.28 The state government’s investigation of the Mendocino wars revealed attitudes toward the Yuki that were shared by settlers and their representatives when faced by Yuki opposition to their encroachments. There were many who found the killings justiied as the only way to deal with the “thieving and murderous” Yuki. Even those who did not like the killings found it hard to consider the Yuki as equals. The Majority Report notes, for example, that one should not “dignify, by the term ‘war,’ the slaughter of beings, who at least possess the human form and who make no resistance and make no attacks, either on the person or the residence of the citizen.” “I do not consider them as hostile,” testified George W. Jeffress, who also maintained the innocence of the Yuki, “but rather as a cowardly thieving set of vagabonds: I do not consider that they are brave when two white men can drive twenty-five of them, and shoot them down while they are running.” The government investigation of the Mendocino war concluded: “History teaches us that the inevitable destiny of the red man is total extermination or isolation from the deadly and corrupting influences of civilization.” The majority of the committee clearly advocated that the Indians should be protected on the reservation and kept separate from the settlers. The problem was that they counted on the federal government to help them do this, but the Army was reluctant to intervene. The San Francisco Bulletin reported, for example: “The United States troops located in that region [Mendocino] are represented to be pursuing, during all these troubles, a ‘masterly course of inactivity.’ Some Army units were even stationed on the reservation. But they could not stop the incessant raiding against Indian villages, and did not have the ability to pursue the criminals outside the reservation borders. As a result, the periodic raids on the reservation continued as the Yuki died in large numbers from hunger and disease

- Norman Naimark, Genocide: A World History (2017)

- In the early decades of California's statehood, the relationship between the State of California and California Native Americans was fraught with violence, exploitation, dispossession and the attempted destruction of tribal communities, as summed up by California's first Governor, Peter Burnett, in his 1851 address to the Legislature: "[t]hat a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected."

- Gavin Newsom, Executive Order N-15-19 (June 2019)

See also

editExternal links

edit- Encyclopedic article on California genocide on Wikipedia

- Media related to California Genocide on Wikimedia Commons