Bede

Anglo-Saxon monk, writer and saint (672/3–735)

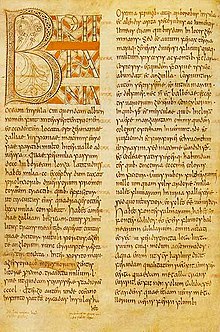

Bede (c. 672/673–26 May 735) was an Anglo-Saxon historian, theologian and scientific writer; often called the Venerable Bede. His best-known work, the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People) was completed in 731.

Quotes

editHistoria Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum ('Ecclesiastical History of the English People')

edit- A. M. Sellar, transl. Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England (London: George Bell & Sons, 1907)

- Dicunt quia die quadam cum, advenientibus nuper mercatoribus, multa venalia in forum fuissent conlata, multi ad emendum confluxissent, et ipsum Gregorium inter alios advenisse, ac vidisse inter alia pueros venales positos candidi corporis ac venusti vultus, capillorum quoque forma egregia. Quos cum adspiceret interrogavit, ut aiunt, de qua regione vel terra essent adlati. Dictumque est quia de Britannia insula, cuius incolae talis essent aspectus.

- It is said that one day, when some merchants had lately arrived at Rome, many things were exposed for sale in the market place, and much people resorted thither to buy: Gregory himself went with the rest, and saw among other wares some boys' put up for sale, of fair complexion, with pleasing countenances, and very beautiful hair. When he beheld them, he asked, it is said, from what region or country they were brought? and was told, from the island of Britain, and that the inhabitants were like that in appearance. He again inquired whether those islanders were Christians, or still involved in the errors of paganism, and was informed that they were pagans. Then fetching a deep sigh from the bottom of his heart, "Alas! what pity," said he, "that the author of darkness should own men of such fair countenances ; and that with such grace of outward form, their minds should be void of inward grace.

- Book II, chapter 1; Bede's source for this story is an anonymous Life of Gregory the Great, written by a monk of Whitby Abbey.

- It is said that one day, when some merchants had lately arrived at Rome, many things were exposed for sale in the market place, and much people resorted thither to buy: Gregory himself went with the rest, and saw among other wares some boys' put up for sale, of fair complexion, with pleasing countenances, and very beautiful hair. When he beheld them, he asked, it is said, from what region or country they were brought? and was told, from the island of Britain, and that the inhabitants were like that in appearance. He again inquired whether those islanders were Christians, or still involved in the errors of paganism, and was informed that they were pagans. Then fetching a deep sigh from the bottom of his heart, "Alas! what pity," said he, "that the author of darkness should own men of such fair countenances ; and that with such grace of outward form, their minds should be void of inward grace.

- Rursus ergo interrogavit quod esset vocabulum gentis illius. Responsum est quod Angli vocarentur. At ille: "Bene", inquit, "nam et angelicam habent faciem et tales angelorum in caelis decet esse cohaeredes. Quod habet nomen ipsa provincia, de qua isti sunt adlati?" Responsum est quod Deiri vocarentur idem provinciales. At ille: "Bene", inquit, "Deiri; de ira eruti, et ad misericordiam Christi vocati. Rex provinciae illius quomodo apellatur?" Responsum est quod Aelli diceretur. At ille adludens ad nomen ait: "Alleluia, laudem Dei creatoris illis in partibus oportet cantari."

- He therefore again asked, what was the name of that nation? and was answered, that they were called Angles. "Right," said he, "for they have an angelic face, and it is meet that such should be co-heirs with the Angels in heaven. What is the name of the province from which they are brought?" It was replied, that the natives of that province were called Deiri. "Truly are they De ira," said he," saved from wrath, and called to the mercy of Christ. How is the king of that province called?" They told him his name was Aelli; and he, playing upon the name, said, "Allelujah, the praise of God the Creator must be sung in those parts."

- Book II, chapter 1; quoting Pope Gregory I

- He therefore again asked, what was the name of that nation? and was answered, that they were called Angles. "Right," said he, "for they have an angelic face, and it is meet that such should be co-heirs with the Angels in heaven. What is the name of the province from which they are brought?" It was replied, that the natives of that province were called Deiri. "Truly are they De ira," said he," saved from wrath, and called to the mercy of Christ. How is the king of that province called?" They told him his name was Aelli; and he, playing upon the name, said, "Allelujah, the praise of God the Creator must be sung in those parts."

- Talis ... mihi uidetur, rex, vita hominum praesens in terris, ad conparationem eius, quod nobis incertum est, temporis, quale cum te residente ad caenam cum ducibus ac ministris tuis tempore brumali, accenso quidem foco in medio, et calido effecto caenaculo, furentibus autem foris per omnia turbinibus hiemalium pluviarum vel nivium, adveniens unus passeium domum citissime pervolaverit; qui cum per unum ostium ingrediens, mox per aliud exierit. Ipso quidem tempore, quo intus est, hiemis tempestate non tangitur, sed tamen parvissimo spatio serenitatis ad momentum excurso, mox de hieme in hiemem regrediens, tuis oculis elabitur. Ita haec vita hominum ad modicum apparet; quid autem sequatur, quidue praecesserit, prorsus ignoramus. Unde si haec nova doctrina certius aliquid attulit, merito esse sequenda videtur.

- The present life of man upon earth, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the house wherein you sit at supper in winter, with your ealdormen and thegns, while the fire blazes in the midst, and the hall is warmed, but the wintry storms of rain or snow are raging abroad. The sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry tempest ; but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, passing from winter into winter again. So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follower what went before we know nothing at all. If, therefore, this new doctrine tells us something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed.

- Book II, chapter 13; quoting one of Edwin of Northumbria's chief men

- The present life of man upon earth, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the house wherein you sit at supper in winter, with your ealdormen and thegns, while the fire blazes in the midst, and the hall is warmed, but the wintry storms of rain or snow are raging abroad. The sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry tempest ; but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, passing from winter into winter again. So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follower what went before we know nothing at all. If, therefore, this new doctrine tells us something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed.

- Tanta eo tempore pax in Britannia fuisse perhibetur, ut, sicut usque hodie in proverbio dicitur, etiamsi mulier una cum recens nato parvulo vellet totam perambulare insulam a mari ad mare, nullo se laedente valeret.

- It is told that there was then such perfect peace in Britain, wheresoever the dominion of King Edwin extended, that, as is still proverbially said, a woman with her new-born babe might walk throughout the island, from sea to sea, without receiving any harm.

- Book II, chapter 16

- It is told that there was then such perfect peace in Britain, wheresoever the dominion of King Edwin extended, that, as is still proverbially said, a woman with her new-born babe might walk throughout the island, from sea to sea, without receiving any harm.

- Fore there neidfaerae • naenig uuiurthit

thoncsnotturra • than him tharf sie

to ymbhycggannae • aer his hiniongae

huaet his gastae • godaes aeththa yflaes

aefter deothdaege • doemid uueorthae.- Northumbrian (Early Anglian) (9th century) — St. Gall MS. 254, p.253, f.127

- For þam nedfere • næni wyrþeþ

þances snotera, • þonne him þearf sy

to gehicgenne • ær his heonengange

hwæt his gaste • godes oþþe yfeles

æfter deaþe heonon • demed weorþe.- West Saxon (Early Saxon) (12th century) — Linc. Coll. Ox. MS. Lat. 31

- Before the dread journey which needs must be taken

No man is more mindful than meet is and right

To ponder, ere hence he departs, what his spirit

Shall, after the death-day, receive as its portion

Of good or of evil, by mandate of doom.- A. S. Cook & C. B. Tinker, Select Translations from Old English Poetry (1902), p. 78

- Glossed in Latin and attributed to Cædmon in Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (731)

- Nū scylun herᵹan • hefaenrīcaes Uard,

metudæs maecti • end his mōdᵹidanc,

uerc Uuldurfadur, • suē hē uundra ᵹihwaes,

ēci dryctin • ōr āstelidæ

hē ǣrist scōp • aelda barnum

heben til hrōfe, • hāleᵹ scepen.

Thā middunᵹeard • moncynnæs Uard,

eci Dryctin, • æfter tīadæ

firum foldu, • Frēa allmectiᵹ.- Northumbrian Version (M) (c. 737) — Camb. Univ. Lib. MS. Kk 5.16, f.128v

- Nu scilun herᵹa • hefenricæs uard

metudæs mehti • and his modᵹithanc

uerc uuldurfadu • sue he uundra ᵹihuæs

eci dryctin • or astelidæ.

he ærist scop • ældu barnum

hefen to hrofæ • haliᵹ sceppend

tha middinᵹard • moncynnæs uard

eci dryctin • æfter tiadæ

firum foldu • frea allmehtiᵹ- Northumbrian Version (P) (c. 746) — St. Pet., Nat. Lib. of Rus. MS. Q.v.I.18, f.107

- Nū þ sculan herian • heofonrices þeard,

metudes myhte • his modᵹeþanc,

þurc þuldorfæder, • sþa he þundra ᵹehþilc,

ece drihten • ord astealde;

he ærest ᵹesceop • ylda bearnum

heofon to hrofe, • haliᵹ scyppend,

middanᵹearde • mancynnes þard;

ece drihtin, • æfter tida

firum on foldum, • frea ællmyhtiᵹ.- West Saxon Version (H) (11th century) — Bodl. Lib. Hatton MS. 43

- Now must we hymn the Master of heaven,

The might of the Maker, the deeds of the Father,

The thought of His heart. He, Lord everlasting,

Established of old the source of all wonders:

Creator all-holy, He hung the bright heaven,

A roof high upreared, o’er the children of men;

The King of mankind then created for mortals

The world in its beauty, the earth spread beneath them,

He, Lord everlasting, omnipotent God.- A. S. Cook & C. B. Tinker, Select Translations from Old English Poetry (1902), p. 77

Quotes about Bede

edit- Bede, like the Vulgate, normally uses the word "gens", not the word "natio", but in his preface's final paragraph he prefers to use the latter when he reaffirms that he had written the "historia nostrae nationis", the history of our own nation. Here, then, in his preface for King Ceolwulf we see the first verbal appearance of the English "nation"... If the nationalism of intellectuals, the Rousseaus, Herders and Fichtes, precedes the existence of nations, as the modernists argue, and it is their "imagining" which brings a nation into being, then Bede is undoubtedly the first, and probably the most influential, such case. It is just that he wrote his books in the eighth, and not the nineteenth century. In his Northumbrian monastery he did indeed imagine England; he did it through intensely biblical glasses, but no less through linguistic and ecclesiastical ones, and he did it so convincingly that no dissentient imagining of his country has ever since seemed quite credible.

- Adrian Hastings, The Construction of Nationhood: Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism (1997), p. 38

- The quality which makes his work great is not his scholarship, nor the faculty of narrative which he shared with many contemporaries, but his astonishing power of co-ordinating the fragments of information which came to him through tradition, the relation of friends, or documentary evidence. In an age when little was attempted beyond the registration of fact, he had reached the conception of history. It is in virtue of this conception that the Historia Ecclesiastica still lives after twelve hundred years.

- Sir Frank Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England (1971), p. 187

- Wyclif does not give Bede as his direct source for the idea that there had existed a state akin to the primitive Church in the English Church before the Conquest. However, it is clear that Bede's entire Historia Ecclesiastica put forth this point of view. Specifically, in his description of the life of St. Augustine and his followers after their arrival in Kent, Bede said that as they began their apostolate, they imitated "the life of the primitive Church"...

It seems that Bede had a concept of a distinct English ecclesiastical tradition. Even the title Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum suggests this. In his epistle to archbishop Egbert, Bede complained about the Church he saw at the end of his own life as having departed from its earlier purity. It seems evident that Wyclif was influenced by Bede in his own development of a similar point of view and the resultant remarkably similar criticisms of his own ecclesiastical contemporaries.- Edith C. Tatnall, 'John Wyclif and Ecclesia Anglicana', Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. XX, No. 1 (April 1969), pp. 36-37

- More and more, as the organic world was observed, the vast multitude of petty animals, winged creatures, and "creeping things" was felt to be a strain upon the sacred narrative. More and more it became difficult to reconcile the dignity of the Almighty with his work in bringing each of these creatures before Adam to be named; or to reconcile the human limitations of Adam with his work in naming "every living creature"; or to reconcile the dimensions of Noah's ark with the space required for preserving all of them, and the food of all sorts necessary for their sustenance. ...Origen had dealt with it by suggesting that the cubit was six times greater than had been supposed. Bede explained Noah's ability to complete so large a vessel by supposing that he worked upon it during a hundred years; and, as to the provision of food taken into it, he declared that there was no need of a supply for more than one day, since God could throw the animals into a deep sleep or otherwise miraculously make one day's supply sufficient; he also lessened the strain on faith still more by diminishing the number of animals taken into the ark—supporting his view upon Augustine's theory of the later development of insects out of carrion.

- Andrew Dickson White, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, Vol. 1 (1896), p. 54

- [H]e, more than anyone else, inspired the idea of the English as one people, called into existence by the special favour of God... It was Bede who gave "Englishness" a manifesto of unique grace and power... Bede's Ecclesiastical History had some of the role in defining English national identity and English national destiny that the narrative books of the Old Testament had for Israel itself, or Homer for the Greeks, or Virgil (rather than Livy) for the Romans.

- Patrick Wormald, 'The Venerable Bede and the ‘Church of the English’', in Geoffrey Rowell (ed.), The English Religious Tradition and the Genius of Anglicanism (1992), pp. 18, 21, 26