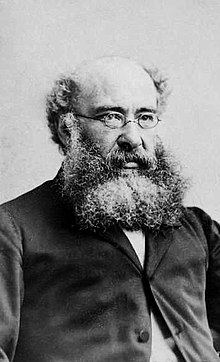

Anthony Trollope

English novelist of the Victorian period (1815-1882)

Anthony Trollope (24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was one of the most successful, prolific and respected English novelists of the Victorian era.

- See also: Phineas Redux

Quotes

edit- [An attorney] can find it consistent with his dignity to turn wrong into right, and right into wrong, to abet a lie, nay to create, disseminate, and with all the play of his wit, give strength to the basest of lies, on behalf of the basest of scoundrels.

- The New Zealander (1965), p. 63; written 1855-6, published posthumously 1965

- Men who cannot believe in the mystery of our Saviour's redemption can believe that spirits from the dead have visited them in a stranger's parlour, because they see a table shake and do not know how it is shaken; because they hear a rapping on a board, and cannot see the instrument that raps it; because they are touched in the dark, and do not know the hand that touches them.

- The New Zealander (1965), p. 73

- Those who have courage to love should have courage to suffer.

- The Bertrams (1859), Ch. 5

- No man thinks there is much ado about nothing when the ado is about himself.

- The Bertrams (1859), Ch. 27

- It would seem that the full meaning of the word marriage can never be known by those who, at their first outspring into life, are surrounded by all that money can give. It requires the single sitting-room, the single fire, the necessary little efforts of self-devotion, the inward declaration that some struggle shall be made for that other one.

- The Bertrams (1859), Ch. 30

- Marvellous is the power which can be exercised, almost unconsciously, over a company, or an individual, or even upon a crowd by one person gifted with good temper, good digestion, good intellects, and good looks.

- Rachel Ray (1863), Ch. 11

- The affair simply amounted to this, that they were to eat their dinner uncomfortably in a field instead of comfortably in the dining room.

- On a picnic, in Can You Forgive Her? (1864), Ch. 78

- Men who can succeed in deceiving no one else will succeed at last in deceiving themselves.

- Miss Mackenzie, Ch. 13. (1865) · Project Gutenburg e-text

- Is it not remarkable that the common repute which we all give to attorneys in the general is exactly opposite to that which every man gives to his own attorney in particular? Whom does anybody trust so implicitly as he trusts his own attorney? And yet is it not the case that the body of attorneys is supposed to be the most roguish body in existence?

- Miss Mackenzie (1865), Ch. 17

- Book love, my friends, is your pass to the greatest, the purest, and the most perfect pleasure that God has prepared for His creatures.

- Speech at the opening of an art exhibition at Bolton Mechanics' Institution (7 December 1868)

- The good and the bad mix themselves so thoroughly in our thoughts, even in our aspirations, that we must look for excellence rather in overcoming evil than in freeing ourselves from its influence.

- He Knew He Was Right (1869), Ch. 60

- It was admitted by all her friends, and also by her enemies — who were in truth the more numerous and active body of the two — that Lizzie Greystock had done very well with herself.

- The Eustace Diamonds (1873) First lines

- To be alone with the girl to whom he is not engaged, is a man's delight; — to be alone with the man to whom she is engaged is the woman's.

- The Eustace Diamonds, Ch. 18

- Love is like any other luxury. You have no right to it unless you can afford it.

- The Way We Live Now, ch. 84. (1875)

- As to that leisure evening of life, I must say that I do not want it. I can conceive of no contentment of which toil is not to be the immediate parent.

- Letter to G W Rusden (8 June 1876), published in The Letters of Anthony Trollope (1983), p. 691

- I judge a man by his actions with men, much more than by his declarations Godwards — When I find him to be envious, carping, spiteful, hating the successes of others, and complaining that the world has never done enough for him, I am apt to doubt whether his humility before God will atone for his want of manliness.

- Letter to G W Rusden (8 June 1876)

- There are words which a man cannot resist from a woman, even though he knows them to be false.

- Is He Popenjoy? (1878), Ch. 18

- It was one of the tenets of her life — the strongest, perhaps, of all those doctrines on which she built her faith — that this world is a world of woe; that wailing and suffering, if not gnashing of teeth, is and should be the condition of mankind preparatory to eternal bliss.

- John Caldigate (1879), Ch. 45

- Next to a sum of money down, a grievance is the best thing you can have. A man who can stick to a grievance year after year will always make money out of it at last.

- John Caldigate, Ch. 53

- The man who worships mere wealth is a snob.

- Thackeray (1879), Ch. 2

- I hold that gentleman to be the best dressed whose dress no one observes. I am not sure but that the same may be said of an author's written language.

- Thackeray, Ch. 9

- Needless to deny that the normal London plumber is a dishonest man. We do not even allow ourselves to think so. That question, as to the dishonesty of mankind generally, is one that disturbs us greatly; — whether a man in all grades of life will by degrees train his honesty to suit his own book, so that the course of life which he shall bring himself to regard as soundly honest shall, if known to his neighbours, subject him to their reproof. We own to a doubt whether the honesty of a bishop would shine bright as the morning star to the submissive ladies who now worship him, if the theory of life upon which he lives were understood by them in all its bearings.

- The Plumber (1880)

- He could find no cure for his grief; but he did know that continued occupation would relieve him, and therefore he occupied himself continually.

- The Life of Cicero (1880)

- A man's mind will very generally refuse to make itself up until it be driven and compelled by emergency.

- Ayala's Angel (1881), Ch. 41

- There are worse things than a lie... I have found... that it may be well to choose one sin in order that another may be shunned.

- Doctor Wortle's School (1881) Ch. 6

- The habit of reading is the only one I know in which there is no alloy. It lasts when all other pleasures fade. It will be there to support you when all other resources are gone. It will be present to you when the energies of your body have fallen away from you. It will make your hours pleasant to you as long as you live.

- As quoted in Forbes (April 1948), p. 42

The Warden (1855)

edit- The Rev. Septimus Harding was, a few years since, a beneficed clergyman residing in the cathedral town of _____; let us call it Barchester. Were we to name Wells or Salisbury, Exeter, Hereford, or Gloucester, it might be presumed that something personal was intended; and as this tale will refer mainly to the cathedral dignitaries of the town in question, we are anxious that no personality may be suspected.

- Ch. 1, first lines

- He was not so anxious to prove himself right, as to be so.

- Ch. 3

- The tenth Muse who now governs the periodical press.

- Ch. 14

Barchester Towers (1857)

edit- In the latter days of July in the year 185-, a most important question was for ten days hourly asked in the cathedral city of Barchester, and answered every hour in various ways — Who was to be the new Bishop?

- First lines

- There is, perhaps, no greater hardship at present inflicted on mankind in civilised and free countries, than the neccessity of listening to sermons.

- Ch. 6

- She well knew the great architectural secret of decorating her constructions, and never descended to construct a decoration.

- Ch. 9

- There is no royal road to learning; no short cut to the acquirement of any art.

- Ch. 20; this derives from an expression attributed to Euclid.

- There is no way of writing well and also of writing easily.

- Ch. 20

- There is no happiness in love, except at the end of an English novel.

- Ch. 27

- Don't let love interfere with your appetite. It never does with mine.

- Ch. 38

- The end of a novel, like the end of a children's dinner-party, must be made up of sweetmeats and sugar-plums.

- Ch. 53

Doctor Thorne (1858)

edit- Before the reader is introduced to the modest country medical practitioner who is to be the chief personage of the following tale, it will be well that he should be made acquainted with some particulars as to the locality in which, and the neighbours among whom, our doctor followed his profession.

- First lines

- One of her instructors in fashion had given her to understand that curls were not the thing. "They'll always pass muster," Miss Dunstable had replied, "when they are done up with bank notes."

- Ch. 16

- There is no road to wealth so easy and respectable as that of matrimony.

- Ch. 18

- In these days a man is nobody unless his biography is kept so far posted up that it may be ready for the national breakfast-table on the morning after his demise.

- Ch. 25

Framley Parsonage (1861)

edit- When young Mark Robarts was leaving college, his father might well declare that all men began to say all good things to him, and to extol his fortune in that he had a son blessed with so excellent a disposition.

- Ch. 1, first lines

- It is a remarkable thing with reference to men who are distressed for money... they never seem at a loss for small sums, or deny themselves those luxuries which small sums purchase. Cabs, dinners, wine, theatres, and new gloves are always at the command of men who are drowned in pecuniary embarrassments, whereas those who don't owe a shilling are so frequently obliged to go without them!

- A man's own dinner is to himself so important that he cannot bring himself to believe that it is a matter utterly indifferent to every one else.

- Ch. 10

- I cannot hold with those who wish to put down the insignificant chatter of the world.

- Ch. 10

- I would recommend all men in choosing a profession to avoid any that may require an apology at every turn; either an apology or else a somewhat violent assertion of right.

- Ch. 15

- Heroes in books should be so much better than heroes got up for the world's common wear and tear

- Ch. 21

- That girls should not marry for money we are all agreed. A lady who can sell herself for a title or an estate, for an income or a set of family diamonds, treats herself as a farmer teats his sheep and oxen — makes hardly more of herself, of her own inner self, in which are comprised a mind and a soul, than the poor wretch of her own sex who earns her bread in the lowest state of degradation.

- Ch. 21

- It is easy to love one's enemy when one is making fine speeches; but so difficult to do so in the actual everyday work of life.

- Ch. 23

- But who ever yet was offered a secret and declined it?

- Ch. 26

Orley Farm (1862)

edit- It is not true that a rose by any other name will smell as sweet. Were it true, I should call this story "The Great Orley Farm Case." But who would ask for the ninth number of a serial work burthened with so very uncouth an appellation? Thence, and therefore, — Orley Farm.

- Ch. 1, first lines.

- There is nothing perhaps so generally consoling to a man as a well-established grievance; a feeling of having been injured, on which his mind can brood from hour to hour, allowing him to plead his own cause in his own court, within his own heart, — and always to plead it successfully.

- Ch. 8

- Success is the necessary misfortune of life, but it is only to the very unfortunate that it comes early.

- Ch. 49

North America (1862)

edit- I know no place at which an Englishman may drop down suddenly among a pleasanter circle of acquaintance, or find himself with a more clever set of men, than he can do at Boston.

- Ch. 2

- If you cross the Atlantic with an American lady you invariably fall in love with her before the journey is over. Travel with the same woman in a railway car for twelve hours, and you will have written her down in your own mind in quite other language than that of love.

- Ch. 11

- Speaking of New York as a traveller I have two faults to find with it. In the first place there is nothing to see; and in the second place there is no mode of getting about to see anything.

- Ch. 14

- Every man worships the dollar, and is down before his shrine from morning to night... Other men, the world over, worship regularly at the shrine with matins and vespers, nones and complines, and whatever other daily services may be known to the religious houses; but the New Yorker is always on his knees.

- Ch. 14

- I have sometimes thought that there is no being so venomous, so bloodthirsty as a professed philanthropist.

- Ch. 16

- Taken altogether, Washington as a city is most unsatisfactory, and falls more grievously short of the thing attempted than any other of the great undertakings of which I have seen anything in the United States.

- Ch. 21

The Small House at Allington (1864)

edit- Of course there was a Great House at Allington. How otherwise should there have been a Small House?

- Ch. 1, first lines

- Let her who is forty call herself forty; but if she can be young in spirit at forty, let her show that she is so.

- Ch. 3

- I doubt whether any girl would be satisfied with her lover's mind if she knew the whole of it.

- Ch. 4

- It may almost be a question whether such wisdom as many of us have in our mature years has not come from the dying out of the power of temptation, rather than as the results of thought and resolution.

- Ch. 14

- Above all things, never think that you're not good enough yourself. A man should never think that. My belief is that in life people will take you very much at your own reckoning.

- Ch. 32

The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867)

editThe Last Chronicle of Barset on Wikisource

- "I can never bring myself to believe it, John," said Mary Walker, the pretty daughter of Mr. George Walker, attorney, of Silverbridge.

- First lines

- She understood how much louder a cock can crow in his own farmyard than elsewhere.

- Vol. I, ch. 17

- Always remember, Mr. Robarts, that when you go into an attorney's office door, you will have to pay for it, first or last.

- Vol. I, ch. 20

- The best way to be thankful is to use the goods the gods provide you.

- Vol. I, ch. 32

- It is a comfortable feeling to know that you stand on your own ground. Land is about the only thing that can't fly away.

- Vol. II, ch. 58

- It's dogged as does it. It's not thinking about it.

- Vol. II, ch. 61

- Nothing reopens the springs of love so fully as absence, and no absence so thoroughly as that which must needs be endless.

- Vol. II, ch. 67

Phineas Finn (1869)

edit- It has been the great fault of our politicians that they have all wanted to do something.

- Ch. 13

- There is such a difference between life and theory.

- Ch. 40

- She knew how to allure by denying, and to make the gift rich by delaying it.

- Ch. 57

- Money is neither god nor devil, that it should make one noble and another vile. It is an accident, and if honestly possessed, may pass from you to me, or from me to you, without a stain.

- Ch. 72, St. Paul's Magazine, April 1869

The Prime Minister (1876)

edit- She had married a vulgar man; and, though she had not become like the man, she had become vulgar.

- Ch. 5

- But as we do not light up our houses with our brightest lamps for all comers, so neither did she emit from her eyes their brightest sparks till special occasions for such shining had arisen.

- Ch. 5

- The girl can look forward to little else than the chance of having a good man for her husband; — a good man, or if her tastes lie in that direction, a rich man.

- Ch. 5

- Power is so pleasant that men quickly learn to be greedy in the enjoyment of it, and to flatter themselves that patriotism requires them to be imperious.

- Ch. 6

- "Aid from heaven you may have," he said, "by saying your prayers; and I don't doubt you ask for this and all other things generally. But an angel won't come to tell you who ought to be Chancellor of the Exchequer."

- Ch. 7

- The town horse, used to gaudy trappings, no doubt despises the work of his country brother; but yet, now and again, there comes upon him a sudden desire to plough.

- Ch. 8

- "I am ready to obey as a child; — but, not being a child, I think I ought to have a reason."

- Ch. 9

- One doesn't have an agreement to that effect written down on parchment and sealed; but it is as well understood and ought to be as faithfully kept as any legal contract.

- Ch. 10

- I always thought there was very little wit wanted to make a fortune in the City.

- Ch. 10

- Had some inscrutable decree of fate ordained and made it certain, with a certainty not to be disturbed, that no candidate could be returned to Parliament who would not assert the earth to be triangular, there would rise immediately a clamorous assertion of triangularity among political aspirants. The test would be innocent. Candidates have swallowed, and daily do swallow, many a worse one. As might be this doctrine of a great triangle, so is the doctrine of Home Rule. Why is a gentleman of property to be kept out in the cold by some O'Mullins because he will not mutter an unmeaning shibboleth? "Triangular? Yes, or lozenge-shaped, if you please; but, gentleman, I am the man for Tipperary."

- Ch. 11

- It is easy for most of us to keep our hands from picking and stealing when picking and stealing plainly lead to prison diet and prison garments. But when silks and satins come of it, and with the silks and satins general respect, the net result of honesty does not seem to be so secure.

- Ch. 11

- This was Barrington Erle, a politician of long standing, who was still looked upon by many as a young man, because he had always been known as a young man, and because he had never done anything to compromise his position in that respect. He had not married, or settled himself down in a house of his own, or become subject to the gout, or given up being careful about the fitting of his clothes.

- Ch. 11

- Your man with a thin skin, a vehement ambition, a scrupulous conscience, and a sanguine desire for rapid improvement is never a happy, and seldom a fortunate politician.

- Ch. 11

- Their support was not needed, therefore they were not courted.

- Ch. 12

- He had so accustomed himself to wield the constitutional cat-of-nine-tails, that heaven will hardly be happy to him unless he be allowed to flog the cherubim.

- Ch. 12

- You can never teach them, except by the slow lesson of habit.

- Ch. 12

- Because we have been removing restraints on Papal aggression, while other nations have been imposing restraints. There are those at Rome who believe all England to be Romish at heart, because here in England a Roman Catholic can say what he will, and print what he will.

- Ch. 12

- Each thought himself, especially since this last promotion, to be indispensably necessary to the formation of London society, and was comfortable in the conviction that he had thoroughly succeeded in life by acquiring the privilege of sitting down to dinner three times a week with peers and peeresses.

- Ch. 20

- He never went very far astray in his official business, because he always obeyed the clerks and followed precedents.

- Ch. 20

- He don't look the sort of fellow I like; but he's got money and he comes here, and he's good looking, — and therefore he'll be a success.

- Ch. 20

- Does not all the world know that when in autumn the Bismarcks of the world, or they who are bigger than Bismarcks, meet at this or that delicious haunt of salubrity, the affairs of the world are then settled in little conclaves, with grater ease, rapidity, and certainty than in large parliaments or the dull chambers of public offices?

- Ch. 20

- The Duke, always right in his purpose but generally wrong in his practice, had stayed at home working all the morning, thereby scandalising the strict, and had gone to church alone in the afternoon, thereby offending the social.

- Ch. 20

- Things to be done offer themselves, I suppose, because they are in themselves desirable; not because it is desirable to have something to do.

- Ch. 20

- You Ministers go on shuffling the old cards till they are so worn out and dirty that one can hardly tell the pips on them.

- Ch. 21

- She certainly had a little syllogism in her head as to the Duke ruling the borough, the Duke's wife ruling the Duke, and therefore the Duke's wife ruling the borough; but she did not think it prudent to utter this on the present occasion.

- Ch. 21

- People seen by the mind are exactly different to things seen by the eye. They grow smaller and smaller as you come nearer down to them, whereas things become bigger.

- Ch. 37

- One wants in a Prime Minister a good many things, but not very great things. He should be clever but need not be a genius; he should be conscientious but by no means strait-laced; he should be cautious but never timid, bold but never venturesome; he should have a good digestion, genial manners, and, above all, a thick skin. These are the gifts we want, but we can't always get them, and have to do without them.

- Ch. 41

- But how shall I excuse it? There are things done which are as holy as the heavens, — which are clear before God as the light of the sun, which leave no stain on the conscience, and which yet the malignity of man can invest with the very blackness of hell!

- Ch. 42

The Duke's Children (1879)

edit- Sir Timothy was a fluent speaker, and when there was nothing to be said was possessed of a great plenty of words. And he was gifted with that peculiar power which enables a man to have the last word in every encounter, — a power which we are apt to call repartee, which is in truth the readiness which comes from continual practice. You shall meet two men of whom you shall know the one to be endowed with the brilliancy of true genius, and the other to be possessed of but moderate parts, and shall find the former never able to hold his own against the latter. In a debate, the man of moderate parts will seem to be greater than the man of genius. But this skill of tongue, this glibness of speech is hardly an affair of intellect at all. It is, — as is style to the writer, — not the wares which he has to take to market, but the vehicle in which they may be carried. Of what avail to you is it to have filled granaries with corn if you cannot get your corn to the consumer? Now Sir Timothy was a great vehicle, but he had not in truth much corn to send.

- Ch. 26

- "I think it is so glorious," said the American. "There is no such mischievous nonsense in all the world as equality. That is what father says. What men ought to want is liberty."

- Ch. 48

- Speeches easy to young speakers are generally very difficult to old listeners.

- Ch. 56

- From all evil against which the law bars you, you should be barred, at an infinite distance, by honour, by conscience, and nobility. Does the law require patriotism, philanthropy, self-abnegation, public service, purity of purpose, devotion to the needs of others who have been placed in the world below you? The law is a great thing, — because men are poor and weak, and bad. And it is great, because where it exists in its strength, no tyrant can be above it. But between you and me there should be no mention of law as the guide of conduct. Speak to me of honour, of duty, and of nobility; and tell me what they require of you.

- Ch. 61

- No one can depute authority. It comes too much from personal accidents, and too little from reason or law to be handed over to others.

- Ch. 66

- When any body of statesmen make public asservations by one or various voices, that there is no discord among them, not a dissentient voice on any subject, people are apt to suppose that they cannot hang together much longer.

- Ch. 71

An Autobiography (1883)

edit- He must have known me had he seen me as he was wont to see me, for he was in the habit of flogging me constantly. Perhaps he did not recognise me by my face.

- Ch. 1

- Satire, though it may exaggerate the vice it lashes, is not justified in creating it in order that it may be lashed.

- Ch. 5

- Take away from English authors their copyrights, and you would very soon take away from England her authors.

- Ch. 6

- Barchester Towers has become one of those novels which do not die quite at once, which live and are read for perhaps a quarter of a century.

- Ch. 6

- A small daily task, if it be really daily, will beat the labors of a spasmodic Hercules.

- Ch. 7

- The satirist who writes nothing but satire should write but little — or it will seem that his satire springs rather from his own caustic nature than from the sins of the world in which he lives.

- Ch. 10

- As will so often be the case when a men has a pen in his hand. It is like a club or sledge-hammer, — in using which, either for defence or attack, a man can hardly measure the strength of the blows he gives.

- Ch. 11

- Three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write.

- Ch. 15

- Of all the needs a book has, the chief need is that it be readable.

- Ch. 19

Quotes about Trollope

edit- Such a work as Orley Farm is perhaps the most satisfactory answer that can be given to so disagreeable an imputation. Here, it may fairly be said, is the precise standard of English taste, sentiment, and conviction. Mr. Trollope has become almost a national institution.

- The National Review, No. XXXI (January 1863), p. 28

- If we pass per saltum from Byron to Anthony Trollope, it is to remark that his works are lacking in those distinctive attributes which belong to a classically trained mind. He himself supplies the clue, remarking that he learned nothing, even of classics — a feat which is worthy of record.

- Of all novelists in any country, Trollope best understands the role of money. Compared with him even Balzac is a romantic.

- W. H. Auden, in Forewords and Afterwords (1973), p. 266

- You knew Anthony Trollope of course. His immeasurable energies had a bewildering effect on my invalid constitution. To me, he was an incarnate gale of wind. He blew off my hat; he turned my umbrella inside out. Joking apart, as good and staunch a friend as ever lived – and, to my mind, a great loss to novel-readers. Never in any marked degree either above or below his own level. In that respect alone, a remarkable writer, surely? If he had lived five years longer, he would have written fifteen more thoroughly readable works of fiction. A loss – a serious loss – I say again.

- Wilkie Collins to William Winter (14 January 1883), quoted in The Letters of Wilkie Collins, Volume 2 1866–1889, eds. William Baker and William M. Clarke (1999), pp. 453-454

- I am much struck in "Rachel" with the skill with which you have organized thoroughly natural everybody incidents into a strictly related, well-proportioned whole, natty and complete as a nut on its stem. Such construction is among those subtleties of art which can hardly be appreciated except by those who have striven after the same result with conscious failure.

- George Eliot to Anthony Trollope (23 October 1863), quoted in Selections from George Eliot's Letters, ed. Gordon S. Haight (1985), p. 290

- But there is something else I care yet more about, which has impressed me very happily in all those writings of yours that I know—it is that people are breathing good bracing air in reading them—it is that they (the books) are filled with belief in goodness without the slightest tinge of maudlin. They are like pleasant public gardens, where people go for amusement and, whether they think of it or not, get health as well.

- George Eliot to Anthony Trollope (23 October 1863), quoted in Selections from George Eliot's Letters, ed. Gordon S. Haight (1985), p. 290

- If the identity between the Mr. Anthony Trollope of private life and the Mr. Anthony Trollope who has enriched English literature with novels that will yet rank as nineteenth-century classics is not immediately perceived, it can only be because the observer is destitute of the faculty of perception. 'The style is the man;' the popular and successful author is the straightforward unreserved friend; the courageous, candid, plain-speaking companion.

- Thomas Hay Sweet Escott, 'A Novelist of the Day', Time (August 1879), p. 627

- I must confess that my theory of men and their resemblance to their works must fall to the ground in Trollope's case, for it would be impossible to imagine anything less like his novels than the author of them. The books, full of gentleness, grace, and refinement; the writer of them, bluff, loud, stormy, and contentious; neither a brilliant talker nor a good speaker; but a kinder-hearted man and a truer friend never lived.

- William Powell Frith, My Autobiography and Reminiscences, Vol. II (1887), p. 335

- I wish Mr. Trollope would go on writing Framley Parsonage for ever. I don't see any reason why it should ever come to an end, and every one I know is always dreading the last number. I hope he will make the jilting of Griselda a long while a-doing.

- Elizabeth Gaskell to George Smith (1 March 1860) quoted in The Letters of Mrs Gaskell, eds. J. A. V. Chapple and Arthur Pollard (1967), p. 602

- I wonder whether it be really true, as I have more than once seen suggested, that the publication of Anthony Trollope's autobiography in some degree accounts for the neglect into which he and his works fell so soon after his death. I should like to believe it, for such a fact would be, from one point of view, a credit to "the great big stupid public." ... Like every other novelist of note, he had two classes of admirers—those who read him for the sake of that excellence which here and there he achieved, and the undistinguishing crowd which found in him a level entertainment. But it would be a satisfaction to think that "the great big stupid" was really, somewhere in its secret economy, offended by that revelation of mechanical methods which made the autobiography either a disgusting or an amusing book to those who read it more intelligently.

- George Gissing, The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903), pp. 212-213

- His hard riding as an overgrown heavy-weight, his systematic whist playing, his loud talk, his burly ubiquity and irrepressible energy in everything,—formed one of the marvels of the last generation. And that such a colossus of blood and bone should spend his mornings, before we were out of bed, in analysing the hypersensitive conscience of an archdeacon, the secret confidences whispered between a prudent mamma and a love-lorn young lady, or the subtle meanderings of Marie Goesler's heart,—this was a real psychologic problem.

- Frederic Harrison, 'Anthony Trollope', Studies in Early Victorian Literature (1895), p. 203

- In any case, his books will hereafter bear a certain historical interest, as the best record of actual manners in the higher English society between 1855 and 1875. That value nothing can take away, however dull, connu, and out of date the books may now seem to our new youth... If our new youth ever could bring itself to take up a book having 1865 on its title-page, it might find in the best of Anthony Trollope much subtle observation, many manly and womanly natures, unfailing purity of tone, and wholesome enjoyment.

- Frederic Harrison, 'Anthony Trollope', Studies in Early Victorian Literature (1895), p. 204

- Nick found a set of Trollope which had a relatively modest and approachable look among the rest, and took down The Way We Live Now, with an armorial bookplate, the pages uncut. "What have you found there?" said Lord Kessler, in a genially possessive tone. "Ah, you're a Trollope man, are you."

"I'm not sure I am, really," said Nick. "I always think he wrote too fast. What was it Henry James said, about Trollope and his 'great heavy shovelfuls of testimony to constituted English matters'?"

Lord Kessler paid a moment's wry respect to this bit of showing-off, but said, "Oh, Trollope's good. He's very good on money."

"Oh...yes..." said Nick, feeling doubly disqualified by his complete ignorance of money and by the aesthetic prejudice which had stopped him from ever reading Trollope.- Alan Hollinghurst, The Line of Beauty (2004), pp. 52-53

- Of its own light kind there has been no better novel ever written than the Last Chronicle of Barset.

- Richard Holt Hutton, review of The Last Chronicle of Barset in The Spectator, No. 2037 (13 July 1867), p. 780

- His great, his inestimable merit was a complete appreciation of the usual... Trollope, therefore, with his eyes comfortably fixed on the familiar, the actual, was far from having invented a new category; his great distinction is that in resting there his vision took in so much of the field. And then he felt all daily and immediate things as well as saw them; felt them in a simple, direct, salubrious way, with their sadness, their gladness, their charm, their comicality, all their obvious and measurable meanings. He never wearied of the pre-established round of English customs—never needed a respite or a change—was content to go on indefinitely watching the life that surrounded him, and holding up his mirror to it.

- Henry James, 'Anthony Trollope', Partial Portraits (1888; 1899), pp. 100-101

- Trollope's genius is not the genius of Shakespeare, but his heroines have something of the fragrance of Imogen and Desdemona.

- Henry James, 'Anthony Trollope', Partial Portraits (1888; 1899), p. 129

- There's been this whole process in the last fifteen years of rediscovering women writers who were either undervalued or just plain forgotten. A great case in point, Margaret Oliphant, a Victorian writer, who I think is better than Trollope, more varied, more interesting-a fascinating writer that no one has ever heard of. She was a better writer than Trollope, and she knew it. She said very bitterly, "I was paid for my best book what Trollope got for his pot boilers." And he ground out potboilers by the score. There has been a misogyny and a stupidity at work, which we are coming out of.

- 1994 interview in Conversations with Ursula Le Guin

- I rather enjoy patronage. I take a lot of trouble over it. At least it makes all those years of reading Trollope seem worthwhile.

- Harold Macmillan, speech in Oxford (June 1959), quoted in D. R. Thorpe, Supermac: The Life of Harold Macmillan (2010), p. 507

- A time-honoured abuse, he held, is frequently less bad than its remedy.

- George Orwell, in "I Have Tried to Tell the Truth", Manchester Evening News, Collected Works, p. 450

- Trollope was a great, truthful, varied artist, who wrote better than he or his contemporaries realized, and who left behind him more novels of lasting value than any other writer in English.

- Gordon N. Ray, 'Trollope at Full Length', Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 4 (August 1968), p. 334

- Crusty, quarrelsome, wrong-headed, prejudiced, obstinate, kind-hearted and thoroughly honest old Tony Trollope. He would have made a capital Conservative County member of the Chaplin or Lowther type.

- George Augustus Henry Sala, inscription on the title page of his copy of Trollope's Autobiography, quoted in Anthony Trollope, An Autobiography (1950), p. xix

- His direct experience of politics...was limited to being an unsuccessful Liberal candidate for Beverley. That doesn't prevent his studies of the human political process – as opposed to his sketches of political ideas, in which he wasn't much interested – being, according to the shrewdest modern parliamentarians, right both in tone and detail.

- C. P. Snow, 'Trollope's Art', in N. John Hall (ed.), The Trollope Critics (1981), p. 172

- Snow cited a private communication from Harold Macmillan as his reference

- They should instead read or re-read The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope, that definitive social satire on the rise and fall of a great financier. It explains more about the developing psychology of a rising financial meteor than column after column in any City page.

- Hugh Stephenson, 'Rarely will so grand a designer have had so little effect', The Times (27 October 1975), p. 16

- Certainly, the Barchester novels tell the truth, and the English truth, at first sight, is almost as plain of feature as the French truth, though with a difference. Mr. Slope is a hypocrite, with a "pawing, greasy way with him". Mrs. Proudie is a domineering bully. The Archdeacon is well-meaning but coarse-grained and thick-cut. Thanks to the vigour of the author, the world of which these are the most prominent inhabitants goes through its daily rigmarole of feeding and begetting children and worshipping with a thoroughness, a gusto, which leaves us no loophole of escape. We believe in Barchester as we believe in the reality of our own weekly bills.

- Virginia Woolf, 'Phases of Fiction', The Bookman, April, May, and June, 1929, quoted in Virginia Woolf, Collected Essays, Volume Two (1966), p. 62

- At the top of his bent Trollope is a big, if not first-rate, novelist, and the top of his bent came when he drove his pen hard and fast after the humours of provincial life and scored, without cruelty but with hale and hearty common sense, the portraits of those well-fed, black-coated, unimaginative men and women of the fifties. In his manner with them, and his manner is marked, there is an admirable shrewdness, like that of a family doctor or solicitor, too well acquainted with human foibles to judge them other than tolerantly and not above the human weakness of liking one person a great deal better than another for no good reason. Indeed, though he does his best to be severe and is at his best when most so, he could not hold himself aloof, but let us know that he loved the pretty girl and hated the oily humbug so vehemently that it is only by a great pull on his reins that he keeps himself straight. It is a family party over which he presides and the reader who becomes, as time goes on, one of Trollope's most intimate cronies has a seat at his right hand. Their relation becomes confidential.

- Virginia Woolf, 'Phases of Fiction', The Bookman, April, May, and June, 1929, quoted in Virginia Woolf, Collected Essays, Volume Two (1966), pp. 62-63