Anna Karenina

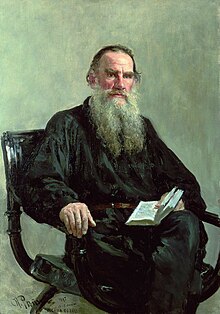

novel by Leo Tolstoy

Anna Karenina is a novel by the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, published in serial installments from 1875 to 1877, that tells the tragic story of a married aristocrat/socialite and her affair with the affluent Count Vronsky.

Quotes

editTranslated by C. Garnett (New York: 2003)

- Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

- Part 1, Chapter 1, p. 5 (opening sentence)

- Stepan Arkadyevitch was a truthful man in his relations with himself. He was incapable of deceiving himself and persuading himself that he repented of his conduct.

- Part 1, Chapter 2, p. 7

- There was no solution, but that universal solution which life gives to all questions, even the most complex and insoluble. That answer is: one must live in the needs of the day—that is, forget oneself. To forget himself in sleep was impossible now, at least till nighttime; … so he must forget himself in the dream of daily life.

- Part 1, Chapter 2, p. 7

- Stepan Arkadyevitch took in and read a liberal paper, not an extreme one, but one advocating the views held by the majority. And in spite of the fact that science, art, and politics had no special interest for him, he firmly held those views on all these subjects which were held by the majority and by his paper, and he only changed them when the majority changed them—or, more strictly speaking, he did not change them, but they imperceptibly changed of themselves within him.

- Part 1, Chapter 3, p. 10

- Stephan Arkadievich chose neither his attitudes nor his opinions, no, the attitudes and opinions came to him on their own, just as he chose neither the style of his hat nor of his coats but got what people were wearing.

- Part 1, Chapter 3

- Stepan Arkadyevitch had not chosen his political opinions or his views; these political opinions and views had come to him of themselves, just as he did not choose the shapes of his hat and coat, but simply took those that were being worn. And for him, living in a certain society—owing to the need, ordinarily developed at years of discretion, for some degree of mental activity—to have views was just as indispensable as to have a hat. If there was a reason for his preferring liberal to conservative views, which were held also by many of his circle, it arose not from his considering liberalism more rational, but from its being in closer accordance with his manner of life. The liberal party said that in Russia everything is wrong, and certainly Stepan Arkadyevitch had many debts and was decidedly short of money. The liberal party said that marriage is an institution quite out of date, and that it needs reconstruction; and family life certainly afforded Stepan Arkadyevitch little gratification, and forced him into lying and hypocrisy, which was so repulsive to his nature. The liberal party said, or rather allowed it to be understood, that religion is only a curb to keep in check the barbarous classes of the people; and Stepan Arkadyevitch could not get through even a short service without his legs aching from standing up, and could never make out what was the object of all the terrible and high-flown language about another world when life might be so very amusing in this world. And with all this, Stepan Arkadyevitch, who liked a joke, was fond of puzzling a plain man by saying that if he prided himself on his origin, he ought not to stop at Rurik and disown the first founder of his family—the monkey. And so Liberalism had become a habit of Stepan Arkadyevitch's.

- Part 1, Chapter 3, p. 10

- Stepan Arkadyevitch … liked his newspaper, as he did his cigar after dinner, for the slight fog it diffused in his brain.

- Part 1, Chapter 3, p. 10

- Levin had been the friend and companion of his early youth. They were fond of one another in spite of the difference of their characters and tastes, as friends are fond of one another who have been together in early youth. But in spite of this, each of them—as is often the way with men who have selected careers of different kinds—though in discussion he would even justify the other's career, in his heart despised it. It seemed to each of them that the life he led himself was the only real life, and the life led by his friend was a mere phantasm.

- Levin and Oblonsky Part 1, Chapter 5, p. 19

- Levin suddenly blushed, not as grown men blush, slightly, without being themselves aware of it, but as boys blush, feeling that they are ridiculous through their shyness, and consequently ashamed of it and blushing still more.

- Part 1, Chapter 5, p. 21

- It was in the Shtcherbatskys' house that he saw for the first time that inner life of an old, noble, cultivated, and honorable family of which he had been deprived by the death of his father and mother. All the members of that family, especially the feminine half, were pictured by him, as it were, wrapped about with a mysterious poetical veil, and he not only perceived no defects whatever in them, but under the poetical veil that shrouded them he assumed the existence of the loftiest sentiments and every possible perfection.

- Levin Part 1, Chapter 6, p. 23

- The childishness of her expression, together with the delicate beauty of her figure, made up her special charm, and that he fully realized. But what always struck him in her as something unlooked for, was the expression of her eyes, soft, serene, and truthful, and above all, her smile, which always transported Levin to an enchanted world, where he felt himself softened and tender, as he remembered himself in some days of his early childhood.

- Levin’s thoughts about Kitty, Part 1, Chapter 9, p. 30

- Now his whole soul was full of remorse that he had begun this conversation with Stepan Arkadyevitch. A feeling such as his was profaned by talk of the rivalry of some Petersburg officer, of the suppositions and the counsels of Stepan Arkadyevitch.

- Levin and Oblonsky, Part 1, Chapter 11, p. 40

- “I've never seen exquisite fallen beings, and I never shall see them, but such creatures as that painted Frenchwoman at the counter with the ringlets are vermin to my mind, and all fallen women are the same. … You're afraid of spiders, and I of these vermin. Most likely you've not made a study of spiders and don't know their character; and so it is with me.”

- Levin, Part 1, Chapter 11, p. 41

- Suddenly both of them felt that though they were friends, though they had been dining and drinking together, which should have drawn them closer, yet each was thinking only of his own affairs, and they had nothing to do with one another. Oblonsky had more than once experienced this extreme sense of aloofness, instead of intimacy, coming on after dinner, and he knew what to do in such cases.

- Levin and Oblonsky Part 1, Chapter 11, p. 42

- The princess for her part, going round the question in the manner peculiar to women, maintained that Kitty was too young, that Levin had done nothing to prove that he had serious intentions, that Kitty felt no great attraction to him, and other side issues; but she did not state the principal point, which was that she looked for a better match for her daughter, and that Levin was not to her liking, and she did not understand him. … She disliked in Levin his strange and uncompromising opinions and his shyness in society, founded, as she supposed, on his pride and his queer sort of life, as she considered it, absorbed in cattle and peasants.

- Part 1, Chapter 12, p. 43

- Princess Shtcherbatskaya … saw that of late years much was changed in the manners of society, that a mother's duties had become still more difficult. She saw that girls of Kitty's age formed some sort of clubs, went to some sort of lectures, mixed freely in men's society; drove about the streets alone, many of them did not curtsey, and, what was the most important thing, all the girls were firmly convinced that to choose their husbands was their own affair, and not their parents'. “Marriages aren't made nowadays as they used to be,” was thought and said by all these young girls, and even by their elders. But how marriages were made now, the princess could not learn from any one. The French fashion—of the parents arranging their children's future—was not accepted; it was condemned. The English fashion of the complete independence of girls was also not accepted, and not possible in Russian society. The Russian fashion of match-making by the offices of intermediate persons was for some reason considered unseemly; it was ridiculed by every one, and by the princess herself. But how girls were to be married, and how parents were to marry them, no one knew. Everyone with whom the princess had chanced to discuss the matter said the same thing: “Mercy on us, it's high time in our day to cast off all that old-fashioned business. It's the young people have to marry; and not their parents; and so we ought to leave the young people to arrange it as they choose.” It was very easy for anyone to say that who had no daughters, but the princess realized that in the process of getting to know each other, her daughter might fall in love, and fall in love with someone who did not care to marry her or who was quite unfit to be her husband. And, however much it was instilled into the princess that in our times young people ought to arrange their lives for themselves, she was unable to believe it, just as she would have been unable to believe that, at any time whatever, the most suitable playthings for children five years old ought to be loaded pistols.

- Part 1, Chapter 12, pp. 44-45

- When she mused on the past, she dwelt with pleasure, with tenderness, on the memories of her relations with Levin. The memories of childhood and of Levin's friendship with her dead brother gave a special poetic charm to her relations with him. His love for her, of which she felt certain, was flattering and delightful to her; and it was pleasant for her to think of Levin. In her memories of Vronsky there always entered a certain element of awkwardness, though he was in the highest degree well-bred and at ease, as though there were some false note—not in Vronsky, he was very simple and nice, but in herself, while with Levin she felt perfectly simple and clear. But, on the other hand, directly she thought of the future with Vronsky, there arose before her a perspective of brilliant happiness; with Levin the future seemed misty.

- Part 1, Chapter 13, p. 46

- There are people who, on meeting a successful rival, no matter in what, are at once disposed to turn their backs on everything good in him, and to see only what is bad. There are people, on the other hand, who desire above all to find in that lucky rival the qualities by which he has outstripped them, and seek with a throbbing ache at heart only what is good. Levin belonged to the second class.

- Part 1, Chapter 14, p. 49

- As for this little Petersburg swell, they're turned out by machinery, all on one pattern, and all precious rubbish.

- Prince Shcherbatsky describing Vronsky, Part 1, Chapter 15, p. 54

- Although he said nothing to her that he could not have said before everybody, he felt that she was becoming more and more dependent upon him, and the more he felt this, the better he liked it, and the tenderer was his feeling for her. He did not know that his mode of behavior in relation to Kitty had a definite character, that it is courting young girls with no intention of marriage, and that such courting is one of the evil actions common among brilliant young men such as he was. It seemed to him that he was the first who had discovered this pleasure, and he was enjoying his discovery.

- If he could have heard what her parents were saying that evening, if he could have put himself at the point of view of the family and have heard that Kitty would be unhappy if he did not marry her, he would have been greatly astonished, and would not have believed it. He could not believe that what gave such great and delicate pleasure to him, and above all to her, could be wrong. Still less could he have believed that he ought to marry.

- Marriage had never presented itself to him as a possibility. He not only disliked family life, but a family, and especially a husband was, in accordance with the views general in the bachelor world in which he lived, conceived as something alien, repellant, and, above all, ridiculous.

- But though Vronsky had not the least suspicion what the parents were saying, he felt on coming away from the Shtcherbatskys' that the secret spiritual bond which existed between him and Kitty had grown so much stronger that evening that some step must be taken. But what step could and ought to be taken he could not imagine.

- Vronsky’s thoughts, Part 1, Chapter 16, pp. 55-56

- “What is so exquisite is that not a word has been said by me or by her, but we understand each other so well in this unseen language of looks and tones, that this evening more clearly than ever she told me she loves me. And how secretly, simply, and most of all, how trustfully! I feel myself better, purer. I feel that I have a heart, and that there is a great deal of good in me. Those sweet, loving eyes!”

- Vronsky’s thoughts, Part 1, Chapter 16, p. 56

- He did not in his heart respect his mother, and without acknowledging it to himself, he did not love her, though in accordance with the ideas of the set in which he lived, and with his own education, he could not have conceived of any behavior to his mother not in the highest degree respectful and obedient, and the more externally obedient and respectful his behavior, the less in his heart he respected and loved her.

- Vronsky’s sentiments, Part 1, Chapter 17, p. 59

- With the insight of a man of the world, from one glance at this lady's appearance Vronsky classified her as belonging to the best society. He begged pardon, and was getting into the carriage, but felt he must glance at her once more; not that she was very beautiful, not on account of the elegance and modest grace which were apparent in her whole figure, but because in the expression of her charming face, as she passed close by him, there was something peculiarly caressing and soft. As he looked round, she too turned her head. Her shining gray eyes, that looked dark from the thick lashes, rested with friendly attention on his face, as though she were recognizing him, and then promptly turned away to the passing crowd, as though seeking someone. In that brief look Vronsky had time to notice the suppressed eagerness which played over her face, and flitted between the brilliant eyes and the faint smile that curved her red lips. It was as though her nature were so brimming over with something that against her will it showed itself now in the flash of her eyes, and now in her smile. Deliberately she shrouded the light in her eyes, but it shone against her will in the faintly perceptible smile.

- Vronky’s reaction to Anna, Part 1, Chapter 18, p. 59

- “You are one of those delightful women in whose company it's sweet to be silent as well as to talk.”

- Countess Vronsky, Part 1, Chapter 18, p. 60

- He saw out of the window how she went up to her brother, put her arm in his, and began telling him something eagerly, obviously something that had nothing to do with him, Vronsky, and at that he felt annoyed.

- Part 1, Chapter 18, p. 61

- “I saw Stiva when he was in love with you. I remember the time when he came to me and cried, talking of you, and all the poetry and loftiness of his feeling for you, and I know that the longer he has lived with you the loftier you have been in his eyes. You know we have sometimes laughed at him for putting in at every word: 'Dolly's a marvelous woman.' You have always been a divinity for him, and you are that still, and this has not been an infidelity of the heart.”

- Anna to Dolly, Part 1, Chapter 19, p. 67

- Kitty felt that Anna was perfectly simple and was concealing nothing, but that she had another higher world of interests inaccessible to her, complex and poetic.

- Part 1, Chapter 20, p. 68

- “I’d so love to know her whole romance,” thought Kitty, recalling the unpoetical appearance of Alexei Alexandrovich, her husband.

- Kitty thinking of Anna, Anna Karenina, R. Pevar, trans. (London: 2000), Part 1, Chapter 20, p. 73

- Levin … remembered how his brother, while at the university, and for a year afterwards, had, in spite of the jeers of his companions, lived like a monk, strictly observing all religious rites, services, and fasts, and avoiding every sort of pleasure, especially women. And afterwards, how he had all at once broken out: he had associated with the most horrible people, and rushed into the most senseless debauchery. …

- Levin remembered that when Nikolay had been in the devout stage, the period of fasts and monks and church services, when he was seeking in religion a support and a curb for his passionate temperament, everyone, far from encouraging him, had jeered at him, and he, too, with the others. They had teased him, called him Noah and Monk; and, when he had broken out, no one had helped him, but everyone had turned away from him with horror and disgust.

- Part 1, Chapter 24, p. 80

- He began to see what had happened to him in quite a different light. He felt himself, and did not want to be any one else. All he wanted now was to be better than before. In the first place he resolved that from that day he would give up hoping for any extraordinary happiness, such as marriage must have given him, and consequently he would not so disdain what he really had.

- Part 1, Chapter 24, p. 86

- Anna Arkadyevna read and understood, but it was distasteful to her to read, that is, to follow the reflection of other people's lives. She had too great a desire to live herself. If she read that the heroine of the novel was nursing a sick man, she longed to move with noiseless steps about the room of a sick man; if she read of a member of Parliament making a speech, she longed to be delivering the speech; if she read of how Lady Mary had ridden after the hounds, and had provoked her sister-in-law, and had surprised everyone by her boldness, she too wished to be doing the same. ** Part 1, Chapter 29, p. 94

- The hero of the novel was already almost reaching his English happiness, a baronetcy and an estate, and Anna was feeling a desire to go with him to the estate, when she suddenly felt that he ought to feel ashamed, and that she was ashamed of the same thing. But what had he to be ashamed of? “What have I to be ashamed of?” she asked herself in injured surprise. She laid down the book and sank against the back of the chair, tightly gripping the paper cutter in both hands. There was nothing. She went over all her Moscow recollections. All were good, pleasant. She remembered the ball, remembered Vronsky and his face of slavish adoration, remembered all her conduct with him: there was nothing shameful. And for all that, at the same point in her memories, the feeling of shame was intensified, as though some inner voice, just at the point when she thought of Vronsky, were saying to her, “Warm, very warm, hot.” “Well, what is it?” she said to herself resolutely, shifting her seat in the lounge. “What does it mean? Am I afraid to look it straight in the face? Why, what is it? Can it be that between me and this officer boy there exist, or can exist, any other relations than such as are common with every acquaintance?”

- Part 1, Chapter 29, p. 94

- Anna ... almost laughed aloud at the feeling of delight that all at once without cause came over her. She felt as though her nerves were strings being strained tighter and tighter on some sort of screwing peg. She felt her eyes opening wider and wider, her fingers and toes twitching nervously, something within oppressing her breathing, while all shapes and sounds seemed in the uncertain half-light to strike her with unaccustomed vividness.

- Part 1, Chapter 29, p. 94

- In spite of the shadow in which he was standing, she saw, or fancied she saw, both the expression of his face and his eyes. It was again that expression of reverential ecstasy which had so worked upon her the day before.

- Part 1, Chapter 30, p. 96

- He had said what her soul longed to hear, though she feared it with her reason.

- Anna’s thoughts upon Vronsky’s declaration that he has come specifically with the intent of seeing her, Part 1, Chapter 30, p. 96

- Though she could not recall her own words or his, she realized instinctively that the momentary conversation had brought them fearfully closer; and she was panic-stricken and blissful at it.

- Anna, Part 1, Chapter 30, p. 97

- An unpleasant sensation gripped at her heart when she met his obstinate and weary glance, as though she had expected to see him different. She was especially struck by the feeling of dissatisfaction with herself that she experienced on meeting him. That feeling was an intimate, familiar feeling, like a consciousness of hypocrisy, which she experienced in her relations with her husband. But hitherto she had not taken note of the feeling, now she was clearly and painfully aware of it.

- Anna and Karenin, Part 1, Chapter 30, p. 97

- “Yes, as you see, your tender spouse, as devoted as the first year after marriage, burned with impatience to see you,” he said in his deliberate, high-pitched voice, and in that tone which he almost always took with her, a tone of jeering at anyone who should say in earnest what he said.

- Part 1, Chapter 30, p. 97

- He felt that all his forces, hitherto dissipated, wasted, were centered on one thing, and bent with fearful energy on one blissful goal.

- Vronsky’s thoughts about Anna, Part 1, Chapter 31, p. 98

- He paused near his compartment, waiting for her to get out. “Once more,” he said to himself, smiling unconsciously, “once more I shall see her walk, her face; she will say something, turn her head, glance, smile, maybe.” But before he caught sight of her, he saw her husband, whom the station-master was deferentially escorting through the crowd. “Ah, yes! The husband.” Only now for the first time did Vronsky realize clearly the fact that there was a person attached to her, a husband. He knew that she had a husband, but had hardly believed in his existence, and only now fully believed in him, with his head and shoulders, and his legs clad in black trousers; especially when he saw this husband calmly take her arm with a sense of property.

- Seeing Alexey Alexandrovitch with his Petersburg face and severely self-confident figure, in his round hat, with his rather prominent spine, he believed in him, and was aware of a disagreeable sensation, such as a man might feel tortured by thirst, who, on reaching a spring, should find a dog, a sheep, or a pig, who has drunk of it and muddied the water. Alexey Alexandrovitch's manner of walking, with a swing of the hips and flat feet, particularly annoyed Vronsky. He could recognize in no one but himself an indubitable right to love her.

- Vronsky’s thoughts of Anna and Karenin, Part 1, Chapter 31, p. 98

- “You set off with the mother and you return with the son,” he said, articulating each syllable, as though each were a separate favor he was bestowing.

- Part 1, Chapter 31, p. 99

- Most fortunate,” he said to his wife, dismissing Vronsky altogether, “that I should just have half an hour to meet you, so that I can prove my devotion,” he went on in the same jesting tone.

- “You lay too much stress on your devotion for me to value it much,” she responded in the same jesting tone.

- Part 1, Chapter 31, p. 100

- Her son, like her husband, aroused in Anna a feeling akin to disappointment. She had imagined him better than he was in reality. She had to let herself drop down to the reality to enjoy him as he really was.

- Part 1, Chapter 32, p. 101

- Countess Lidia Ivanovna, though she was interested in everything that did not concern her, had a habit of never listening to what interested her.

- Lidia Ivanovna, Part 1, Chapter 32, p. 101

- “I'm beginning to be weary of fruitlessly championing the truth.”

- Part 1, Chapter 32, p. 101

- “It was all the same before, of course; but why was it I didn't notice it before?” Anna asked herself. “Or has she been very much irritated today? It's really ludicrous; her object is doing good; she a Christian, yet she's always angry; and she always has enemies, and always enemies in the name of Christianity and doing good.”

- Part 1, Chapter 32, p. 102

- Every minute of Alexey Alexandrovitch's life was portioned out and occupied. And to make time to get through all that lay before him every day, he adhered to the strictest punctuality. “Unhasting and unresting,” was his motto.

- Part 1, Chapter 33, p. 103

- Anna ... knew, too, that in spite of his official duties, which swallowed up almost the whole of his time, he considered it his duty to keep up with everything of note that appeared in the intellectual world. She knew, too, that he was really interested in books dealing with politics, philosophy, and theology, that art was utterly foreign to his nature; but, in spite of this, or rather, in consequence of it, Alexey Alexandrovitch never passed over anything in the world of art, but made it his duty to read everything. She knew that in politics, in philosophy, in theology, Alexey Alexandrovitch often had doubts, and made investigations; but on questions of art and poetry, and, above all, of music, of which he was totally devoid of understanding, he had the most distinct and decided opinions.

- Part 1, Chapter 33, p. 104

- “He's a good man; truthful, good-hearted, and remarkable in his own line,” Anna said to herself going back to her room, as though she were defending him to someone who had attacked him and said that one could not love him.

- Anna thinking of her husband, Part 1, Chapter 33, p. 105

- Vronsky heard with pleasure this light-hearted prattle of a pretty woman, agreed with her, gave her half-joking counsel, and altogether dropped at once into the tone habitual to him in talking to such women. In his Petersburg world all people were divided into utterly opposed classes. One, the lower class, vulgar, stupid, and, above all, ridiculous people, who believe that one husband ought to live with the one wife whom he has lawfully married; that a girl should be innocent, a woman modest, and a man manly, self-controlled, and strong; that one ought to bring up one's children, earn one's bread, and pay one's debts; and various similar absurdities. This was the class of old-fashioned and ridiculous people. But there was another class of people, the real people. To this class they all belonged, and in it the great thing was to be elegant, generous, plucky, gay, to abandon oneself without a blush to every passion, and to laugh at everything else.

- Part 1, Chapter 34, p. 107

- At first Anna sincerely believed that she was displeased with him for daring to pursue her. Soon after her return from Moscow, on arriving at a soiree where she had expected to meet him, and not finding him there, she realized distinctly from the rush of disappointment that she had been deceiving herself, and that this pursuit was not merely not distasteful to her, but that it made the whole interest of her life.

- Part 2, Chapter 4, p.

- Though his conviction that jealousy was a shameful feeling and that one ought to feel confidence had not broken down, he felt that he was standing face to face with something illogical and irrational, and did not know what was to be done. Alexey Alexandrovitch was standing face to face with life, with the possibility of his wife's loving someone other than himself, and this seemed to him very irrational and incomprehensible because it was life itself. All his life Alexey Alexandrovitch had lived and worked in official spheres, having to do with the reflection of life. And every time he had stumbled against life itself he had shrunk away from it. Now he experienced a feeling akin to that of a man who, wile calmly crossing a precipice by a bridge, should suddenly discover that the bridge is broken, and that there is a chasm below. That chasm was life itself, the bridge that artificial life in which Alexey Alexandrovitch had lived.

- Part 2, Chapter 8, p. 134

- There, looking at her table, with the malachite blotting case lying at the top and an unfinished letter, his thoughts suddenly changed. He began to think of her, of what she was thinking and feeling. For the first time he pictured vividly to himself her personal life, her ideas, her desires, and the idea that she could and should have a separate life of her own seemed to him so alarming that he made haste to dispel it. It was the chasm which he was afraid to peep into. To put himself in thought and feeling in another person's place was a spiritual exercise not natural to Alexey Alexandrovitch. He looked on this spiritual exercise as a harmful and dangerous abuse of the fancy.

- Part 2, Chapter 8, p. 135

- “The question of her feelings, of what has passed and may be passing in her soul, that's not my affair; that's the affair of her conscience, and falls under the head of religion,” he said to himself, feeling consolation in the sense that he had found to which division of regulating principles this new circumstance could be properly referred.

- Karenin Part 2, Chapter 8, p. 135

- She looked at him so simply, so brightly, that anyone who did not know her as her husband knew her could not have noticed anything unnatural, either in the sound or the sense of her words. But to him, knowing her, knowing that whenever he went to bed five minutes later than usual, she noticed it, and asked him the reason; to him, knowing that every joy, every pleasure and pain that she felt she communicated to him at once; to him, now to see that she did not care to notice his state of mind, that she did not care to say a word about herself, meant a great deal. He saw that the inmost recesses of her soul, that had always hitherto lain open before him, were closed against him. More than that, he saw from her tone that she was not even perturbed at that, but as it were said straight out to him: “Yes, it's shut up, and so it must be, and will be in future.” Now he experienced a feeling such as a man might have, returning home and finding his own house locked up.

- Anna and Karenin Part 2, Chapter 9, p. 137

- “Perhaps I am mistaken, but believe me, what I say, I say as much for myself as for you. I am your husband, and I love you.”

- For an instant her face fell, and the mocking gleam in her eyes died away; but the word love threw her into revolt again. She thought: “Love? Can he love? If he hadn't heard there was such a thing as love, he would never have used the word. He doesn't even know what love is.”

- Karenin and Anna Part 2, Chapter 9, p. 138

- He felt what a murderer must feel, when he sees the body he has robbed of life. That body, robbed by him of life, was their love, the first stage of their love. There was something awful and revolting in the memory of what had been bought at this fearful price of shame. Shame at their spiritual nakedness crushed her and infected him. But in spite of all the murderer's horror before the body of his victim, he must hack it to pieces, hide the body, must use what he has gained by his murder.

- And with fury, as it were with passion, the murderer falls on the body, and drags it and hacks at it; so he covered her face and shoulders with kisses.

- Vronsky and Anna, Part 2, Chapter 11, p. 140

- In addition to his farming, which called for special attention in spring, and in addition to reading, Levin had begun that winter a work on agriculture, the plan of which turned on taking into account the character of the laborer on the land as one of the unalterable data of the question, like the climate and the soil, and consequently deducing all the principles of scientific culture, not simply from the data of soil and climate, but from the data of soil, climate, and a certain unalterable character of the laborer.

- Part 2, Chapter 12, p. 142

- Spring is the time of plans and projects. And, as he came out into the farmyard, Levin, like a tree in spring that knows not what form will be taken by the young shoots and twigs imprisoned in its swelling buds, hardly knew what undertakings he was going to begin upon now in the farm work that was so dear to him.

- Part 2, Chapter 13, p. 144

- The bailiff listened attentively, and obviously made an effort to approve of his employer's projects. But still he had that look Levin knew so well that always irritated him, a look of hopelessness and despondency. That look said: “That's all very well, but as God wills.”

- Nothing mortified Levin so much as that tone. But it was the tone common to all the bailiffs he had ever had. They had all taken up that attitude to his plans, and so now he was not angered by it, but mortified, and felt all the more roused to struggle against this, as it seemed, elemental force continually ranged against him, for which he could find no other expression than “as God wills.”

- Part 2, Chapter 13, p. 146

- “Come, this is life! How splendid it is! This is how I should like to live!”

- “Why, who prevents you?” said Levin, smiling.

- “No, you're a lucky man! You've got everything you like. You like horses—and you have them; dogs—you have them; shooting—you have it; farming—you have it.”

- “Perhaps because I rejoice in what I have, and don't fret for what I haven't.”

- Oblonsky and Levin, Part 2, Chapter 14, p. 151

- “Woman, don't you know, is such a subject that however much you study it, it's always perfectly new.”

- “Well, then, it would be better not to study it.”

- “No. Some mathematician has said that enjoyment lies in the search for truth, not in the finding it.”

- Oblonsky and Levin, Part 2, Chapter 14, p. 152

- Levin smiled contemptuously. “I know,” he thought, “that fashion not only in him, but in all city people, who, after being twice in ten years in the country, pick up two or three phrases and use them in season and out of season, firmly persuaded that they know all about it. 'Timber, run to so many yards the acre.' He says those words without understanding them himself.”

- “I wouldn't attempt to teach you what you write about in your office,” said he, “and if need arose, I should come to you to ask about it. But you're so positive you know all the lore of the forest. It's difficult. Have you counted the trees?”

- Oblonsky and Levin, Part 2, Chapter 16, p. 156

- “Your honors have been diverting yourselves with the chase? What kind of bird may it be, pray?” added Ryabinin, looking contemptuously at the snipe: “a great delicacy, I suppose.” And he shook his head disapprovingly, as though he had grave doubts whether this game were worth the candle.

- “Would you like to go into my study?” Levin said in French to Stepan Arkadyevitch, scowling morosely. “Go into my study; you can talk there.”

- “Quite so, where you please,” said Ryabinin with contemptuous dignity, as though wishing to make it felt that others might be in difficulties as to how to behave, but that he could never be in any difficulty about anything.

- On entering the study Ryabinin looked about, as his habit was, as though seeking the holy picture, but when he had found it, he did not cross himself. He scanned the bookcases and bookshelves, and with the same dubious air with which he had regarded the snipe, he smiled contemptuously and shook his head disapprovingly, as though by no means willing to allow that this game were worth the candle.

- Part 2, Chapter 16, p. 157

- Kitty was not married, but ill, and ill from love for a man who had slighted her. This slight, as it were, rebounded upon him. Vronsky had slighted her, and she had slighted him, Levin. Consequently Vronsky had the right to despise Levin, and therefore he was his enemy. But all this Levin did not think out. He vaguely felt that there was something in it insulting to him.

- Part 2, Chapter 17, p. 159

- “Still, how you do treat him!” said Oblonsky. “You didn't even shake hands with him. Why not shake hands with him?”

- “Because I don't shake hands with a waiter, and a waiter's a hundred times better than he is.”

- Oblonsky and Levin speaking about Ryabinin, Part 2, Chapter 17, p. 159

- “You talk of his being an aristocrat. But allow me to ask what it consists in, that aristocracy of Vronsky or of anybody else, beside which I can be looked down upon? You consider Vronsky an aristocrat, but I don't. A man whose father crawled up from nothing at all by intrigue. ... No, excuse me, but I consider myself aristocratic, and people like me, who can point back in the past to three or four honorable generations of their family, of the highest degree of breeding (talent and intellect, of course that's another matter), and have never curried favor with anyone, never depended on anyone for anything, like my father and my grandfather. And I know many such. ... We are aristocrats, and not those who can only exist by favor of the powerful of this world.

- Oblonsky and Levin speaking about Ryabinin, Part 2, Chapter 17, p. 161

- This elder son, too, was displeased with his younger brother. He did not distinguish what sort of love his might be, big or little, passionate or passionless, lasting or passing, but he knew that this love affair was viewed with displeasure by those whom it was necessary to please, and therefore he did not approve of his brother's conduct.

- describing the Vronky brothers, Part 2, Chapter 18, p. 163

- Vronsky had several times already, though not so resolutely as now, tried to bring her to consider their position, and every time he had been confronted by the same superficiality and triviality with which she met his appeal now. It was as though there were something in this which she could not or would not face, as though directly she began to speak of this, she, the real Anna, retreated somehow into herself, and another strange and unaccountable woman came out, whom he did not love, and whom he feared, and who was in opposition to him.

- Part 2, Chapter 23, p. 176

- In his attitude to her there was a shade of vexation, but nothing more. “You would not be open with me,” he seemed to say, mentally addressing her; “so much the worse for you. Now you may beg as you please, but I won't be open with you. So much the worse for you!” he said mentally, like a man who, after vainly attempting to extinguish a fire, should fly in a rage with his vain efforts and say, “Oh, very well then! you shall burn for this!” This man, so subtle and astute in official life, did not realize all the senselessness of such an attitude to his wife. He did not realize it, because it was too terrible to him to realize his actual position, and he shut down and locked and sealed up in his heart that secret place where lay hid his feelings towards his family.

- Part 2, Chapter 26, p. 187

- If anyone had had the right to ask Alexey Alexandrovitch what he thought of his wife's behavior, the mild and peaceable Alexey Alexandrovitch would have made no answer, but he would have been greatly angered with any man who should question him on that subject. For this reason there positively came into Alexey Alexandrovitch's face a look of haughtiness and severity whenever anyone inquired after his wife's health. Alexey Alexandrovitch did not want to think at all about his wife's behavior, and he actually succeeded in not thinking about it at all.

- Part 2, Chapter 26, p. 187

- He did not want to see, and did not see, that many people in society cast dubious glances on his wife; he did not want to understand, and did not understand, why his wife had so particularly insisted on staying at Tsarskoe, where Betsy was staying, and not far from the camp of Vronsky's regiment. He did not allow himself to think about it, and he did not think about it; but all the same though he never admitted it to himself, and had no proofs, not even suspicious evidence, in the bottom of his heart he knew beyond all doubt that he was a deceived husband, and he was profoundly miserable about it.

- How often during those eight years of happy life with his wife Alexey Alexandrovitch had looked at other men's faithless wives and other deceived husbands and asked himself: “How can people descend to that? how is it they don't put an end to such a hideous position?” But now, when the misfortune had come upon himself, he was so far from thinking of putting an end to the position that he would not recognize it at all, would not recognize it just because it was too awful, too unnatural.

- Part 2, Chapter 26, pp. 187-188

- She watched his progress towards the pavilion, saw him now responding condescendingly to an ingratiating bow, now exchanging friendly, nonchalant greetings with his equals, now assiduously trying to catch the eye of some great one of this world, and taking off his big round hat that squeezed the tips of his ears. All these ways of his she knew, and all were hateful to her. “Nothing but ambition, nothing but the desire to get on, that's all there is in his soul,” she thought; “as for these lofty ideals, love of culture, religion, they are only so many tools for getting on.”

- Anna watching her husband, Part 2, Chapter 28, p. 192

- The adjutant-general expressed his disapproval of races. Alexey Alexandrovitch replied defending them. Anna heard his high, measured tones, not losing one word, and every word struck her as false, and stabbed her ears with pain. … She was in an agony of terror for Vronsky, but a still greater agony was the never-ceasing, as it seemed to her, stream of her husband's shrill voice. …

- “I'm a wicked woman, a lost woman,” she thought; “but I don't like lying, I can't endure falsehood, while as for him (her husband) it's the breath of his life—falsehood. He knows all about it, he sees it all; what does he care if he can talk so calmly? If he were to kill me, if he were to kill Vronsky, I might respect him. No, all he wants is falsehood and propriety,” Anna said to herself, not considering exactly what it was she wanted of her husband, and how she would have liked to see him behave. She did not understand either that Alexey Alexandrovitch's peculiar loquacity that day, so exasperating to her, was merely the expression of his inward distress and uneasiness. As a child that has been hurt skips about, putting all his muscles into movement to drown the pain, in the same way Alexey Alexandrovitch needed mental exercise to drown the thoughts of his wife that in her presence and in Vronsky's, and with the continual iteration of his name, would force themselves on his attention. And it was as natural for him to talk well and cleverly, as it is natural for a child to skip about.

- Part 2, Chapter 28, p. 193

- Mademoiselle Varenka … always seemed absorbed in work about which there could be no doubt, and so it seemed she could not take interest in anything outside it. It was just this contrast with her own position that was for Kitty the great attraction of Mademoiselle Varenka. Kitty felt that in her, in her manner of life, she would find an example of what she was now so painfully seeking: interest in life, a dignity in life—apart from the worldly relations of girls with men, which so revolted Kitty, and appeared to her now as a shameful hawking about of goods in search of a purchaser.

- Part 2, Chapter 30, p. 200

- Kitty made the acquaintance of Madame Stahl too, and this acquaintance, together with her friendship with Varenka, did not merely exercise a great influence on her, it also comforted her in her mental distress. She found this comfort through a completely new world being opened to her by means of this acquaintance, a world having nothing in common with her past, an exalted, noble world, from the height of which she could contemplate her past calmly. It was revealed to her that besides the instinctive life to which Kitty had given herself up hitherto there was a spiritual life. This life was disclosed in religion, but a religion having nothing in common with that one which Kitty had known from childhood, and which found expression in litanies and all-night services at the Widow's Home, where one might meet one's friends, and in learning by heart Slavonic texts with the priest. This was a lofty, mysterious religion connected with a whole series of noble thoughts and feelings, which one could do more than merely believe because one was told to, which one could love.

- Part 2, Chapter 33, p. 207

- The views of the prince and of the princess on life abroad were completely opposed. The princess thought everything delightful, and in spite of her established position in Russian society, she tried abroad to be like a European fashionable lady, which she was not—for the simple reason that she was a typical Russian gentlewoman; and so she was affected, which did not altogether suit her. The prince, on the contrary, thought everything foreign detestable, got sick of European life, kept to his Russian habits, and purposely tried to show himself abroad less European than he was in reality.

- Part 2, Chapter 34, p. 210

- The news of Kitty's friendship with Madame Stahl and Varenka, and the reports the princess gave him of some kind of change she had noticed in Kitty, troubled the prince and aroused his habitual feeling of jealousy of everything that drew his daughter away from him, and a dread that his daughter might have got out of the reach of his influence into regions inaccessible to him.

- Part 2, Chapter 34, p. 211

- “What is a Pietist, papa?” asked Kitty, dismayed to find that what she prized so highly in Madame Stahl had a name.

- Part 2, Chapter 34, p. 212

- She felt that the heavenly image of Madame Stahl, which she had carried for a whole month in her heart, had vanished, never to return, just as the fantastic figure made up of some clothes thrown down at random vanishes when one sees that it is only some garment lying there. All that was left was a woman with short legs, who lay down because she had a bad figure, and worried patient Varenka for not arranging her rug to her liking. And by no effort of the imagination could Kitty bring back the former Madame Stahl.

- Part 2, Chapter 34, p. 214

- Everyone was good humored, but Kitty could not feel good humored, and this increased her distress. She felt a feeling such as she had known in childhood, when she had been shut in her room as a punishment, and had heard her sisters' merry laughter outside.

- Part 2, Chapter 35, pp. 215-216

- “It serves me right, because it was all sham; because it was all done on purpose, and not from the heart. ...”

- “A sham! with what object?” said Varenka gently. …

- “To seem better to people, to myself, to God; to deceive everyone. No! now I won't descend to that. I'll be bad; but anyway not a liar, a cheat. … I can't act except from the heart, and you act from principle. I liked you because I liked you, but you probably only wanted to save me, to improve me.”

- “You are unjust,” said Varenka.

- Part 2, Chapter 35, pp. 217-218

- With her father's coming all the world in which she had been living was transformed for Kitty. She did not give up everything she had learned, but she became aware that she had deceived herself in supposing she could be what she wanted to be. Her eyes were, it seemed, opened; she felt all the difficulty of maintaining herself without hypocrisy and self-conceit on the pinnacle to which she had wished to mount.

- describing Kitty, Part 2, Chapter 35, p. 218

- Konstantin Levin regarded his brother as a man of immense intellect and culture, as generous in the highest sense of the word, and possessed of a special faculty for working for the public good. But in the depths of his heart, the older he became, and the more intimately he knew his brother, the more and more frequently the thought struck him that this faculty of working for the public good, of which he felt himself utterly devoid, was possibly not so much a quality as a lack of something—not a lack of good, honest, noble desires and tastes, but a lack of vital force, of what is called heart, of that impulse which drives a man to choose some one out of the innumerable paths of life, and to care only for that one. The better he knew his brother, the more he noticed that Sergey Ivanovitch, and many other people who worked for the public welfare, were not led by an impulse of the heart to care for the public good, but reasoned from intellectual considerations that it was a right thing to take interest in public affairs, and consequently took interest in them. Levin was confirmed in this generalization by observing that his brother did not take questions affecting the public welfare or the question of the immortality of the soul a bit more to heart than he did chess problems, or the ingenious construction of a new machine.

- Part 3, Chapter 1, p. 224

- Konstantin Levin did not like talking and hearing about the beauty of nature. Words for him took away the beauty of what he saw.

- Part 3, Chapter 2, p. 226

- You are altogether, as the French say, too primesautière a nature; you must have intense, energetic action, or nothing.

- Part 3, Chapter 6, p. 242

- Darya Alexandrovna had done her hair, and dressed with care and excitement. In the old days she had dressed for her own sake to look pretty and be admired. Later on, as she got older, dress became more and more distasteful to her. She saw that she was losing her good looks. But now she began to feel pleasure and interest in dress again. Now she did not dress for her own sake, not for the sake of her own beauty, but simply that as the mother of those exquisite creatures she might not spoil the general effect. And looking at herself for the last time in the looking-glass she was satisfied with herself. She looked nice. Not nice as she would have wished to look nice in old days at a ball, but nice for the object which she now had in view.

- Part 3, Chapter 8, p. 247

- “I got a note from Stiva that you were here.”

- “From Stiva?” Darya Alexandrovna asked with surprise.

- “Yes; he writes that you are here, and that he thinks you might allow me to be of use to you,” said Levin, and as he said it he became suddenly embarrassed, and, stopping abruptly, he walked on in silence by the wagonette, snapping off the buds of the lime trees and nibbling them. He was embarrassed through a sense that Darya Alexandrovna would be annoyed by receiving from an outsider help that should by rights have come from her own husband. Darya Alexandrovna certainly did not like this little way of Stepan Arkadyevitch's of foisting his domestic duties on others. And she was at once aware that Levin was aware of this. It was just for this fineness of perception, for this delicacy, that Darya Alexandrovna liked Levin.

- Part 3, Chapter 9, p. 250

- The children knew Levin very little, and could not remember when they had seen him, but they experienced in regard to him none of that strange feeling of shyness and hostility which children so often experience towards hypocritical, grown-up people, and for which they are so often and miserably punished. Hypocrisy in anything whatever may deceive the cleverest and most penetrating man, but the least wide-awake of children recognizes it, and is revolted by it, however ingeniously it may be disguised. Whatever faults Levin had, there was not a trace of hypocrisy in him, and so the children showed him the same friendliness that they saw in their mother's face.

- Part 3, Chapter 9, p. 250

- Levin, to turn the conversation, explained to Darya Alexandrovna the theory of cow-keeping, based on the principle that the cow is simply a machine for the transformation of food into milk, and so on. …

- “Yes, but still all this has to be looked after, and who is there to look after it?” Darya Alexandrovna responded, without interest.

- She had by now got her household matters so satisfactorily arranged, thanks to Marya Philimonovna, that she was disinclined to make any change in them; besides, she had no faith in Levin's knowledge of farming. General principles, as to the cow being a machine for the production of milk, she looked on with suspicion. It seemed to her that such principles could only be a hindrance in farm management. It all seemed to her a far simpler matter.

- Part 3, Chapter 9, p. 251

- “That pride you so despise makes any thought of Katerina Alexandrovna out of the question for me,—you understand, utterly out of the question.”

- “I will only say one thing more: you know that I am speaking of my sister, whom I love as I love my own children. I don't say she cared for you, all I meant to say is that her refusal at that moment proves nothing.”

- “I don't know!” said Levin, jumping up. “If you only knew how you are hurting me. It's just as if a child of yours were dead, and they were to say to you: He would have been like this and like that, and he might have lived, and how happy you would have been in him. But he's dead, dead, dead!...”

- Part 3, Chapter 10, p. 254

- “What have you come for, Tanya?” she said in French to the little girl who had come in.

- “Where's my spade, mamma?”

- “I speak French, and you must too.”

- The little girl tried to say it in French, but could not remember the French for spade; the mother prompted her, and then told her in French where to look for the spade. And this made a disagreeable impression on Levin.

- Everything in Darya Alexandrovna's house and children struck him now as by no means so charming as a little while before. “And what does she talk French with the children for?” he thought; “how unnatural and false it is! And the children feel it so: Learning French and unlearning sincerity,” he thought to himself, unaware that Darya Alexandrovna had thought all that over twenty times already, and yet, even at the cost of some loss of sincerity, believed it necessary to teach her children French in that way.

- Part 3, Chapter 10, p. 254

- The whole meadow and distant fields all seemed to be shaking and singing to the measures of this wild merry song with its shouts and whistles and clapping. Levin felt envious of this health and mirthfulness; he longed to take part in the expression of this joy of life. But he could do nothing, and had to lie and look on and listen. When the peasants, with their singing, had vanished out of sight and hearing, a weary feeling of despondency at his own isolation, his physical inactivity, his alienation from this world, came over Levin.

- Some of the very peasants who had been most active in wrangling with him over the hay, some whom he had treated with contumely, and who had tried to cheat him, those very peasants had greeted him goodhumoredly, and evidently had not, were incapable of having any feeling of rancor against him, any regret, any recollection even of having tried to deceive him. All that was drowned in a sea of merry common labor. God gave the day, God gave the strength. And the day and the strength were consecrated to labor, and that labor was its own reward. For whom the labor? What would be its fruits? These were idle considerations—beside the point.

- Part 3, Chapter 12, p. 258

- In the coach was an old lady dozing in one corner, and at the window, evidently only just awake, sat a young girl holding in both hands the ribbons of a white cap. With a face full of light and thought, full of a subtle, complex inner life. … At the very instant when this apparition was vanishing, the truthful eyes glanced at him. She recognized him, and her face lighted up with wondering delight.

- He could not be mistaken. There were no other eyes like those in the world. There was only one creature in the world that could concentrate for him all the brightness and meaning of life. It was she. It was Kitty.

- Levin and Kitty, Part 3, Chapter 12, p. 259

- “I made a mistake in linking my life to hers; but there was nothing wrong in my mistake, and so I cannot be unhappy. It's not I that am to blame,” he told himself.

- Karnein Part 3, Chapter 2, p. 261

- Though in passing through these difficult moments he had not once thought of seeking guidance in religion, yet now, when his conclusion corresponded, as it seemed to him, with the requirements of religion, this religious sanction to his decision gave him complete satisfaction, and to some extent restored his peace of mind.

- Karenin Part 3, Chapter 13, p. 264

- She repeated continually, “My God! my God!” But neither “God” nor “my” had any meaning to her. The idea of seeking help in her difficulty in religion was as remote from her as seeking help from Alexey Alexandrovitch himself, although she had never had doubts of the faith in which she had been brought up. She knew that the support of religion was possible only upon condition of renouncing what made up for her the whole meaning of life.

- Anna Part 3, Chapter 15, pp. 269-270

- She began to feel alarm at the new spiritual condition, never experienced before, in which she found herself. She felt as though everything were beginning to be double in her soul, just as objects sometimes appear double to over-tired eyes.

- Anna Part 3, Chapter 15, p. 270

- “He's right!” she said; “of course, he's always right; he's a Christian, he's generous! Yes, vile, base creature! And no one understands it except me, and no one ever will; and I can't explain it. They say he's so religious, so high-principled, so upright, so clever; but they don't see what I've seen. They don't know how he has crushed my life for eight years, crushed everything that was living in me—he has not once even thought that I'm a live woman who must have love. … He's doing just what's characteristic of his mean character. He'll keep himself in the right, while me, in my ruin, he'll drive still lower to worse ruin yet.”

- Anna thinking of Karenin, Part 3, Chapter 16, p. 273

- He knows that I can't repent that I breathe, that I love; he knows that it can lead to nothing but lying and deceit; but he wants to go on torturing me. I know him; I know that he's at home and is happy in deceit, like a fish swimming in the water.

- Anna thinking of Karenin, Part 3, Chapter 16, p. 273

- These two ladies were the chief representatives of a select new Petersburg circle, nicknamed, in imitation of some imitation, les sept merveilles du monde.

- Part 3, Chapter 16, p. 275

- I can't stay very long with you. I'm forced to go on to old Madame Vrede. I've been promising to go for a century,” said Anna, to whom lying, alien as it was to her nature, had become not merely simple and natural in society, but a positive source of satisfaction.

- Part 3, Chapter 17, p. 276

- Liza now is one of those naïve natures that, like children, don't know what's good and what's bad. Anyway, she didn't comprehend it when she was very young. And now she's aware that the lack of comprehension suits her. Now, perhaps, she doesn't know on purpose.

- Betsy, Part 3, Chapter 17, p. 278

- There was something in her higher than what surrounded her. There was in her the glow of the real diamond among glass imitations. This glow shone out in her exquisite, truly enigmatic eyes. The weary, and at the same time passionate, glance of those eyes, encircled by dark rings, impressed one by its perfect sincerity. Everyone looking into those eyes fancied he knew her wholly, and knowing her, could not but love her.

- Anna’s thoughts about Liza, Part 3, Chapter 13, p. 280

- Vronsky's life was particularly happy in that he had a code of principles, which defined with unfailing certitude what he ought and what he ought not to do. This code of principles covered only a very small circle of contingencies, but then the principles were never doubtful, and Vronsky, as he never went outside that circle, had never had a moment's hesitation about doing what he ought to do. These principles laid down as invariable rules: that one must pay a cardsharper, but need not pay a tailor; that one must never tell a lie to a man, but one may to a woman; that one must never cheat anyone, but one may a husband; that one must never pardon an insult, but one may give one and so on. These principles were possibly not reasonable and not good, but they were of unfailing certainty, and so long as he adhered to them, Vronsky felt that his heart was at peace and he could hold his head up.

- Part 3, Chapter 20, p. 284

- What the laborer wanted was to work as pleasantly as possible, with rests, and above all, carelessly and heedlessly, without thinking. ... All they wanted was to work merrily and carelessly, and his interests were not only remote and incomprehensible to them, but fatally opposed to their most just claims.

- Part 3, Chapter 24, p. 299

- Sviazhsky was one of those people, always a source of wonder to Levin, whose convictions, very logical though never original, go one way by themselves, while their life, exceedingly definite and firm in its direction, goes its way quite apart and almost always in direct contradiction to their convictions.

- Part 3, Chapter 26, p. 304

- If it had not been a characteristic of Levin's to put the most favorable interpretation on people, Sviazhsky's character would have presented no doubt or difficulty to him: he would have said to himself, “a fool or a knave,” and everything would have seemed clear. But he could not say “a fool,” because Sviazhsky was unmistakably clever, and moreover, a highly cultivated man, who was exceptionally modest over his culture. There was not a subject he knew nothing of. But he did not display his knowledge except when he was compelled to do so. Still less could Levin say that he was a knave, as Sviazhsky was unmistakably an honest, good-hearted, sensible man, who worked good-humoredly, keenly, and perseveringly at his work; he was held in high honor by everyone about him, and certainly he had never consciously done, and was indeed incapable of doing, anything base.

- Levin tried to understand him, and could not understand him, and looked at him and his life as at a living enigma.

- Levin and he were very friendly, and so Levin used to venture to sound Sviazhsky, to try to get at the very foundation of his view of life; but it was always in vain. Every time Levin tried to penetrate beyond the outer chambers of Sviazhsky's mind, which were hospitably open to all, he noticed that Sviazhsky was slightly disconcerted; faint signs of alarm were visible in his eyes, as though he were afraid Levin would understand him, and he would give him a kindly, good-humored repulse.

- Part 3, Chapter 26, pp. 304-305

- The landowner unmistakably spoke his own individual thought—a thing that very rarely happens—and a thought to which he had been brought not by a desire of finding some exercise for an idle brain, but a thought which had grown up out of the conditions of his life, which he had brooded over in the solitude of his village, and had considered in every aspect.

- Part 3, Chapter 26, p. 308

- “Come, tell us how does your land do—does it pay?” said Levin, and at once in Sviazhsky's eyes he detected that fleeting expression of alarm which he had noticed whenever he had tried to penetrate beyond the outer chambers of Sviazhsky's mind.

- Part 3, Chapter 27, p. 310

- And in the happiest frame of mind Sviazhsky got up and walked off, apparently supposing the conversation to have ended at the very point when to Levin it seemed that it was only just beginning.

- Part 3, Chapter 27, p. 310

- The landowner, like all men who think independently and in isolation, was slow in taking in any other person's idea, and particularly partial to his own.

- Part 3, Chapter 27, p. 310

- Sviazhsky, once more checking Levin in his inconvenient habit of peeping into what was beyond the outer chambers of his mind, went to see his guests out.

- Part 3, Chapter 27, p. 311

- He wondered, as he heard Sviazhsky: “What is there inside of him? And why, why is he interested in the partition of Poland?” When Sviazhsky had finished, Levin could not help asking: “Well, and what then?” But there was nothing to follow. It was simply interesting that it had been proved to be so and so. But Sviazhsky did not explain, and saw no need to explain why it was interesting to him.

- Part 3, Chapter 28, p. 312

- “But how do schools help matters?”

- “They give the peasant fresh wants.”

- “Well, that's a thing I've never understood,” Levin replied with heat. “In what way are schools going to help the people to improve their material position? You say schools, education, will give them fresh wants. So much the worse, since they won't be capable of satisfying them. And in what way a knowledge of addition and subtraction and the catechism is going to improve their material condition, I never could make out. The day before yesterday, I met a peasant woman in the evening with a little baby, and asked her where she was going. She said she was going to the wise woman; her boy had screaming fits, so she was taking him to be doctored. I asked, 'Why, how does the wise woman cure screaming fits?' 'She puts the child on the hen-roost and repeats some charm....' “

- “Well, you're saying it yourself! What's wanted to prevent her taking her child to the hen-roost to cure it of screaming fits is just...” Sviazhsky said, smiling good-humoredly.

- “Oh, no!” said Levin with annoyance; “that method of doctoring I merely meant as a simile for doctoring the people with schools. The people are poor and ignorant—that we see as surely as the peasant woman sees the baby is ill because it screams. But in what way this trouble of poverty and ignorance is to be cured by schools is as incomprehensible as how the hen-roost affects the screaming. What has to be cured is what makes him poor.”

- Part 3, Chapter 28, p. 313

- But there was a gleam of alarm in Sviazhsky's eyes. ... Levin saw that he was not to discover the connection between this man's life and his thoughts. Obviously he did not care in the least what his reasoning led him to; all he wanted was the process of reasoning. And he did not like it when the process of reasoning brought him into a blind alley. That was the only thing he disliked, and avoided by changing the conversation to something agreeable and amusing. ... This dear good Sviazhsky, keeping a stock of ideas simply for social purposes, and obviously having some other principles hidden from Levin, while with the crowd, whose name is legion, he guided public opinion by ideas he did not share.

- Part 3, Chapter 28, p. 314

- Let us try to look upon the labor force not as an abstract force, but as the Russian peasant with his instincts, and we shall arrange our system of culture in accordance with that. Imagine ... that you have found means of making your laborers take an interest in the success of the work.

- Levin’s thoughts, Part 3, Chapter 28, p. 315

- Another difficulty lay in the invincible disbelief of the peasant that a landowner's object could be anything else than a desire to squeeze all he could out of them. They were firmly convinced that his real aim (whatever he might say to them) would always be in what he did not say to them. And they themselves, in giving their opinion, said a great deal but never said what was their real object. ... Talking to the peasants and explaining to them all the advantages of the plan, Levin felt that the peasants heard nothing but the sound of his voice, and were firmly resolved, whatever he might say, not to let themselves be taken in.

- Part 3, Chapter 29, p. 316

- “I mean that I'm acting for my own advantage. It's all the better for me if the peasants do their work better.”

- “Well, whatever you do, if he's a lazy good-for-nought, everything'll be at sixes and sevens. If he has a conscience, he'll work, and if not, there's no doing anything.”

- “Oh, come, you say yourself Ivan has begun looking after the cattle better.”

- “All I say is,” answered Agafea Mihalovna, evidently not speaking at random, but in strict sequence of idea, “that you ought to get married, that's what I say.”

- Part 3, Chapter 30, p. 321

- The chief reason why the prince was so particularly disagreeable to Vronsky was that he could not help seeing himself in him. And what he saw in this mirror did not gratify his self-esteem.

- Part 4, Chapter 1, p. 332

- She was, every time she saw him, making the picture of him in her imagination (incomparably superior, impossible in reality) fit with him as he really was.

- Part 4, Chapter 2, p. 334

- These fits of jealousy, which of late had been more and more frequent with her, horrified him, and however much he tried to disguise the fact, made him feel cold to her, although he knew the cause of her jealousy was her love for him. How often he had told himself that her love was happiness; and now she loved him as a woman can love when love has outweighed for her all the good things of life—and he was much further from happiness than when he had followed her from Moscow. Then he had thought himself unhappy, but happiness was before him; now he felt that the best happiness was already left behind. She was utterly unlike what she had been when he first saw her. Both morally and physically she had changed for the worse. She had broadened out all over, and in her face at the time when she was speaking of the actress there was an evil expression of hatred that distorted it. He looked at her as a man looks at a faded flower he has gathered, with difficulty recognizing in it the beauty for which he picked and ruined it.

- Part 4, Chapter 3, p. 335

- “If you want him defined, here he is: a prime, well-fed beast such as takes medals at the cattle shows, and nothing more,” he said, with a tone of vexation that interested her.

- “No; how so?” she replied. “He's seen a great deal, anyway; he's cultured?”

- “It's an utterly different culture—their culture. He's cultivated, one sees, simply to be able to despise culture, as they despise everything but animal pleasures.”

- Vronky and Anna discussing the visiting Prince, Part 4, Chapter 3, p. 336

- “I know him, the falsity in which he's utterly steeped?... Could one, with any feeling, live as he is living with me? He understands nothing, and feels nothing. Could a man of any feeling live in the same house with his unfaithful wife? Could he talk to her, call her 'my dear'? ... He's not a man, he's an official machine. He doesn't understand that I'm your wife, that he's outside, that he's superfluous.”

- Anna speaking about Karenin, Part 4, Chapter 3, p. 337

- The new commission for the inquiry into the condition of the native tribes in all its branches had been formed and dispatched to its destination with an unusual speed and energy inspired by Alexey Alexandrovitch. Within three months a report was presented. The condition of the native tribes was investigated in its political, administrative, economic, ethnographic, material, and religious aspects. To all these questions there were answers admirably stated, and answers admitting no shade of doubt, since they were not a product of human thought, always liable to error, but were all the product of official activity. The answers were all based on official data furnished by governors and heads of churches, and founded on the reports of district magistrates and ecclesiastical superintendents, founded in their turn on the reports of parochial overseers and parish priests; and so all of these answers were unhesitating and certain. All such questions as, for instance, of the cause of failure of crops, of the adherence of certain tribes to their ancient beliefs, etc.—questions which, but for the convenient intervention of the official machine, are not, and cannot be solved for ages—received full, unhesitating solution.

- Part 4, Chapter 6, p. 346

- "This whole world of ours is only a speck of mildew sprung up on a tiny planet."

- Levin speaking to Oblonsky, Part 4, Chapter 7

- “It cannot be denied that the influence of the classical authors is in the highest degree moral, while, unfortunately, with the study of the natural sciences are associated the false and noxious doctrines which are the curse of our day.” ...

- “One must allow that to weigh all the advantages and disadvantages of classical and scientific studies is a difficult task, and the question which form of education was to be preferred would not have been so quickly and conclusively decided if there had not been in favor of classical education, as you expressed it just now, its moral—disons le mot—anti-nihilist influence.”

- Karenin and Sergey Ivanovich LevPart 4, Chapter 10, p. 361

- Levin had often noticed in discussions between the most intelligent people that after enormous efforts, and an enormous expenditure of logical subtleties and words, the disputants finally arrived at being aware that what they had so long been struggling to prove to one another had long ago, from the beginning of the argument, been known to both, but that they liked different things, and would not define what they liked for fear of its being attacked. He had often had the experience of suddenly in a discussion grasping what it was his opponent liked and at once liking it too, and immediately he found himself agreeing, and then all arguments fell away as useless. Sometimes, too, he had experienced the opposite, expressing at last what he liked himself, which he was devising arguments to defend, and, chancing to express it well and genuinely, he had found his opponent at once agreeing and ceasing to dispute his position. He tried to say this.

- She knitted her brow, trying to understand. But directly he began to illustrate his meaning, she understood at once.

- “I know: one must find out what he is arguing for, what is precious to him, then one can...”

- She had completely guessed and expressed his badly expressed idea. Levin smiled joyfully; he was struck by this transition from the confused, verbose discussion with Pestsov and his brother to this laconic, clear, almost wordless communication of the most complex ideas.

- Part 4, Chapter 13, p. 369

- They arrived at the meeting. Levin heard the secretary hesitatingly read the minutes which he obviously did not himself understand; but Levin saw from this secretary's face what a good, nice, kind-hearted person he was. This was evident from his confusion and embarrassment in reading the minutes. Then the discussion began. They were disputing about the misappropriation of certain sums and the laying of certain pipes, and Sergey Ivanovitch was very cutting to two members, and said something at great length with an air of triumph; and another member, scribbling something on a bit of paper, began timidly at first, but afterwards answered him very viciously and delightfully. And then Sviazhsky (he was there too) said something too, very handsomely and nobly. Levin listened to them, and saw clearly that these missing sums and these pipes were not anything real, and that they were not at all angry, but were all the nicest, kindest people, and everything was as happy and charming as possible among them. They did no harm to anyone, and were all enjoying it. What struck Levin was that he could see through them all today, and from little, almost imperceptible signs knew the soul of each, and saw distinctly that they were all good at heart. And Levin himself in particular they were all extremely fond of that day. That was evident from the way they spoke to him, from the friendly, affectionate way even those he did not know looked at him.

- Part 4, Chapter 14, p. 372

- Levin ... had thought his engagement would have nothing about it like others, that the ordinary conditions of engaged couples would spoil his special happiness; but it ended in his doing exactly as other people did, and his happiness being only increased thereby and becoming more and more special, more and more unlike anything that had ever happened.

- Part 4, Chapter 16, p. 378

- His confession of unbelief passed unnoticed. She was religious, had never doubted the truths of religion, but his external unbelief did not affect her in the least. Through love she knew all his soul, and in his soul she saw what she wanted, and that such a state of soul should be called unbelieving was to her a matter of no account.

- Part 4, Chapter 16, p. 379

- The nervous agitation of Alexey Alexandrovitch kept increasing, and had by now reached such a point that he ceased to struggle with it. He suddenly felt that what he had regarded as nervous agitation was on the contrary a blissful spiritual condition that gave him all at once a new happiness he had never known. He did not think that the Christian law that he had been all his life trying to follow, enjoined on him to forgive and love his enemies; but a glad feeling of love and forgiveness for his enemies filled his heart.

- Part 4, Chapter 18, p. 383

- At his sick wife's bedside he had for the first time in his life given way to that feeling of sympathetic suffering always roused in him by the sufferings of others, and hitherto looked on by him with shame as a harmful weakness. And pity for her, and remorse for having desired her death, and most of all, the joy of forgiveness, made him at once conscious, not simply of the relief of his own sufferings, but of a spiritual peace he had never experienced before. He suddenly felt that the very thing that was the source of his sufferings had become the source of his spiritual joy; that what had seemed insoluble while he was judging, blaming, and hating, had become clear and simple when he forgave and loved.

- Part 4, Chapter 19, p. 388

- Alexey Alexandrovitch ... felt that besides the blessed spiritual force controlling his soul, there was another, a brutal force, as powerful, or more powerful, which controlled his life, and that this force would not allow him that humble peace he longed for.

- Part 4, Chapter 19, p. 389