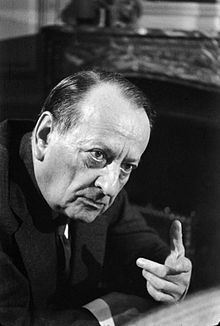

André Malraux

French novelist, art theorist, and statesman

André Georges Malraux (November 3 1901 – November 23, 1976) was a French novelist, adventurer, art historian and statesman. He served as Minister for Cultural Affairs from 1958 to 1969.

Quotes

edit- No one can endure his own solitude.

- Author's commentary, serialized version of La condition humaine in the Nouvelle revue française (1933)

- The human mind invents its Puss-in-Boots and its coaches that change into pumpkins at midnight because neither the believer nor the atheist is completely satisfied with appearances.

- Antimémoires, preface (1967)

- What is man? A miserable little pile of secrets.

- Antimémoires, preface (1967)

- This preface paraphrases a line of dialogue from his own earlier work: "A man is what he hides: a miserable little pile of secrets." ("L'homme est ce qu'il cache : un misérable petit tas de secrets.") Les Noyers de l'Altenburg (1943)

- Our civilization … is not devaluing its awareness of the unknowable; nor is it deifying it. It is the first civilization that has severed it from religion and superstition. In order to question it.

- Picasso's Mask (1976)

- Chanel, General De Gaulle and Picasso are the three most important figures of our time.

- As quoted in Paris, Paris : Journey Into the City of Light (2005) by David Downie, p. 87

- The artist is not the transcriber of the world, he is its rival.

- L'Intemporel

- On this earth of ours where everything is subject to the passing of time, one thing only is both subject to time and yet victorious over it: the work of art.

- André Malraux, TV program: Promenades imaginaires dans Florence, 1975.

- On peut aimer que le sens du mot “art” soit tenter de donner conscience à des hommes de la grandeur qu’ils ignorent en eux.

- André Malraux, Préface du Temps du mépris (1935), Malraux citations sur www.fondationandremalraux.org

- The West regards as truth what the Hindu regards as appearance (for if human life, in the age of Christendom, was doubtless an ordeal it was certainly truth and not illusion), and the Westerner can regard knowledge of the the universe as the supreme value, while for the Hindu the supreme value is accession to the divine Absolute....

But the most profound difference is based on the fact that the fundamental reality for the West, Christian or athiest, is death, in whatever sense it may be interpreted --- while the fundamental reality for India is the endlessness of life in the endlessness of time: Who can kill immortality?- As attributed and quoted in Londhe, S. (2008). A tribute to Hinduism: Thoughts and wisdom spanning continents and time about India and her culture. New Delhi: Pragun Publication.

La condition humaine [Man's Fate] (1933)

edit- If a man is not ready to risk his life, where is his dignity?

- The great mystery is not that we should have been thrown down here at random between the profusion of matter and that of the stars; it is that from our very prison we should draw, from our own selves, images powerful enough to deny our own nothingness.

- The attempt to force human beings to despise themselves… is what I call hell.

- Section 2

- "Why do you fight?" ... He kept his wife, his kid, from dying. That was nothing. Less than nothing. If he had had money, if he could have left it to them, he would have been free to go and get killed. As if the universe had not treated him all his life with kicks in the belly, it now despoiled him of the only dignity he could ever possess — his death.

- The sons of torture victims make good terrorists.

- La liberté n'est pas un échange, c'est la liberté.

- Freedom is not an exchange — it is freedom.

L'espoir [Man's Hope] (1938)

edit- One cannot create an art that speaks to me when one has nothing to say.

- Il n'y a pas cinquante manières de combattre, il n'y en a qu'une, c'est d'être vainqueur. Ni la révolution ni la guerre ne consistent à se plaire à soi-même.

- There are not fifty ways of fighting, there is only one, and that is to win. Neither revolution nor war consists in doing what one pleases.

- Part 2, Section 2, Chapter 12

- There are not fifty ways of fighting, there is only one, and that is to win. Neither revolution nor war consists in doing what one pleases.

Les voix du silence [Voices of Silence] (1951)

edit- Could we bring ourselves to feel what the first spectators of an Egyptian statue, or a Romanesque crucifixion, felt, we would make haste to remove them from the Louvre. True, we are trying more and more to gauge the feelings of those first spectators, but without forgetting our own, and we can be contented all the more easily with the mere knowledge of the former, without experiencing them, because all we wish to do is put this knowledge to the work of art.

- Part I, Chapter III

- A large share of our art heritage is now derived from peoples whose idea of art was quite other than ours, and even from peoples to whom the very idea of art meant nothing.

- Part I, Chapter V

- Though man's feeling for the other-worldly often has recourse to solitude, solitude does not foster its development; rather, it is nourished by communion, to which the church is more propitious than the cemetery.

- Part II, Chapter III

- The ordinary man puts up a struggle against all that is not himself, whereas it is against himself, in a limited but all-essential field, that the artist has to battle.

- Part III, Chapter III

- The present age delights in unearthing a great man's secrets; for one thing because we like to temper our admiration and also perhaps we have a vague hope of finding a clue to genius in such "revelations."

- Part III, Chapter VI

- If modern painters feel qualms about applying the term "masterpiece" to describe a work of capital importance, this is because it has come to convey a notion of perfection: a notion that leads to much confusion when applied to artists other than those who made perfection their ideal.

- Part III, Chapter VI

- Once the masterpiece has emerged, the lesser works surrounding it fall into place; and it then gives the impression of having been led up to and foreseeable, though actually it is inconceivable — or, rather, it can only be conceived of once it is there for us to see it. It is not a scene that has come alive, but a latent potentiality that has materialized. Suppose that one of the world's masterpieces were to disappear, leaving no trace behind it, not even a reproduction; even the completest knowledge of its maker's other works would not enable the next generation to visualize it. All the rest of Leonardo's oeuvre would not enable us to visualize the Mona Lisa; all Rembrandt's, the Three Crosses or The Prodigal Son; all Vermeer's, The Love Letter; all Titian's, the Venice Pietà; all medieval sculpture, the Chartres Kings or the Naumburg Uta. What would another picture by the Master of Villeneuve look like? How could even the most careful study of The Embarkation for Cythera, or indeed that of all Watteau's other works conjure up L'Enseigne de Gersaint, had it disappeared?

- Part III, Chapter VI

- Athirst for personal salvation, the West forgets that many religions had but a vague notion of the life beyond the grave; true, all great religions stake a claim on eternity, but not necessarily on man's eternal life.

- Part IV, Chapter I

- Surely that little pseudo-gothic church on Broadway, hidden amongst the skyscrapers, is symbolic of the age! On the whole face of the globe the civilization that has conquered it has failed to build a temple or a tomb.

- Part IV, Chapter I

- An individualism which has got beyond the stage of hedonism tends to yield to the lure of the grandiose. It was not man, the individual, nor even the Supreme Being, that Robespierre set up against Christ; it was that Leviathan, the Nation.

- Part IV, Chapter I

- Each form of the sacrosanct was regarded by members of the culture which gave rise to it as a revelation of the Truth; at Byzantium it was not a mere hypothesis that was sponsored by the majesty of the Byzantine style. To us, however, these forms make their appeal as forms alone — in other words, as they would be were they the work of a contemporary (and, since this actually is unthinkable, they affect us in a puzzling manner); or else as so many grandiose vestiges of a faith that has died out. We look at them from outside; they are still emotive, but they are no longer true. Thus we deprive them of what was their most vital element; for a religious civilization that regarded what it revered as a mere hypothesis is inconceivable.

- Part IV, Chapter V

- The great Christian art did not die because all possible forms had been used up; it died because faith was being transformed into piety. Now, the same conquest of the outside world that brought in our modern individualism, so different from that of the Renaissance, is by way of relativizing the individual. It is plain to see that man's faculty of transformation, which began by a remaking of the natural world, has ended by calling man himself into question.

- André Malraux, Les voix du silence [Voices of Silence] (1951) Part IV, Chapter VI

- In ceasing to subordinate creative power to any supreme value, modern art has brought home to us the presence of that creative power throughout the whole history of art.

- Part IV, Chapter VI

- History may clarify our understanding of the supreme work of art, but can never account for it completely; for the Time of art is not the same as the Time of history.

- Part IV, Chapter VI

- Our art culture makes no attempt to search the past for precedents, but transforms the entire past into a sequence of provisional responses to a problem that remains intact.

- Part IV, Chapter VII

- Our characteristic response to the mutilated statue, the bronze dug up from the earth, is revealing. It is not that we prefer time-worn bas-reliefs, or rusted statuettes as such, nor is it the vestiges of death that grip us in them, but those of life. Mutilation is the scar left by the struggle with Time, and a reminder of it — Time which is as much a part of ancient works of art as the material they are made of, and thrusts up through the fissures, from a dark underworld, where all is at once chaos and determinism.

- Part IV, Chapter VII

- L'art est un anti-destin.

- Art is a revolt against fate.

- Part IV, Chapter VII

- Art is a revolt against fate.

Quotes about Malraux

edit- Malraux offers a revolutionary understanding of the nature and significance of art and, in doing so, also provides a glimpse of a new humanism — a “tragic humanism” to borrow his own phrase — which, unlike the optimistic idealisms inherited from the nineteenth century, is compatible with the agnosticism and disenchantment of the world in which we now live.

- Derek Allan, in Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux’s Theory of Art (2009)

- André Malraux, the French novelist who had fought in the Spanish Civil War, now offered to take up arms again with the Mukti Bahini—which might have been somewhat more intimidating to Yahya if he had not been seventy years old.

- About the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Bass, G. J. (2014). The Blood telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a forgotten genocide. ch 16

- In behalf of the American people, I extend my deepest sympathy to you and to the people of France on the passing of Andre Malraux. France has lost one of her finest sons. Modern civilization has lost a dynamic and creative spirit. The deep concern of Andre Malraux for his fellow man, his contributions to shaping a better world, and his creativity as a philosopher, novelist, and historian will endure as a lasting memorial.

- Gerald Ford; Message to President Valery Giscard d'Estaing of France on the Death of Andre Malraux Online, The American Presidency Project; 23 November 1976

- When I first looked at Walker Evans's photographs, I thought of something Malraux wrote: "To transform destiny into awareness." One is embarrassed to want so much for oneself. But, how else are you going to justify your failure and your effort?

- Robert Frank Art Is the Highest Form of Hope & Other Quotes by Artists by Phaidon (2016)

- Malraux's career begins in mystery with the expedition to Indo-China, the obscure affair of the missing statues, a short term of imprisonment, and a plunge into Eastern politics. The details of these matters are still unknown to us, but it is their resonance that counts. With all their shadow and uncertainty they nevertheless suggest a purity of adventure. Malraux entered the European consciousness not as a writer but as an event, as a symbolic figure somehow combining the magical qualities of youth and heroism with a sense of unlimited promise.

- William Righter in The Rhetorical Hero (1964)

- At its deepest level, Malraux’s thinking about art is inseparable from an understanding of the significance of man, and especially man in contemporary, agnostic, Western, and Westernised, cultures. There is no question of art as a substitute religion, and Malraux draws a sharp distinction between the function of art and the function of an absolute. There is unmistakably, however, an insistence on the profound human importance of art, especially today in civilizations bereft of any fundamental value.

- Derek Allan, in Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux’s Theory of Art (2009)

- Intelligence suraiguë, culture littéraire et artistique sans égale, don évident de la parole, passion de l’honneur, de l’action, de la camaraderie. Tout est là pour permettre d’affirmer que la vie de Malraux n’a pas fini d’étonner.

- Georges Pompidou, dans André Malraux, Pages choisies, Hachette, Classiques illustrés Vaubourdolle, 1955 on Fondation Andre Malraux