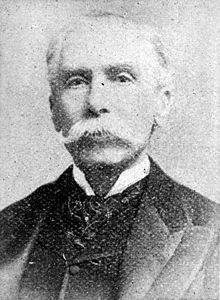

Alfred Austin

Alfred Austin DL (30 May 1835 – 2 June 1913) was an English poet who was appointed Poet Laureate in 1896.

Quotes

editThe Golden Age: A Satire (1871)

editLondon: Chapman and Hall, 1871

- Then, without toil, by vale and mountain side,

Men found their few and simple wants supplied;

Plenty, like dew, dropped subtle from the air,

And Earth's fair gifts rose prodigal as prayer.

Love, with no charms except its own to lure,

Was swiftly answered by a love as pure.

No need for wealth; each glittering fruit and flower,

Each star, each streamlet, made the maiden's dower.- pp. 2–3.

- Lo, where huge London, huger day by day,

O'er six fair counties spreads its hideous sway.- p. 66.

- And Clara dies that Claribel may dance.

- p. 75.

Savonarola (1881)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1881

- Let your house

Be spacious more than splendid, and be books

And busts your most conspicuous furniture.- Lorenzo de' Medici in Act I, sc. i; p. 6.

- Friendship craves

The commerce of the mind, not the exchange

Of emulous feasts that foster sycophants.- Lorenzo de' Medici in Act I, sc. i; pp. 6–7.

- Know, Nature, like the cuckoo, laughs at law,

Placing her eggs in whatso nest she will.- Lorenzo de' Medici in Act I, sc. i; p. 14.

- Friendship, 'tis said, is love without his wings,

And friendship, sir, is sweet enough for me.- Candida to Valori in Act I, sc. ii; p. 35.

- Death is the looking-glass of life wherein

Each man may scan the aspect of his deeds.- Girolamo Savonarola in Act I, sc. iv; p. 49.

- Your logic may be good,

But dialectics never saved a soul.- Frà Domenico in Act II, sc. ix; p. 197.

- […] there is no love,

That merits such high christening, but is built

Firm upon some foundation out of sight;

God, country, virtue, something not ourself,

To which ourself is nothing, save the proof

Of its invisible sureness.- Candida to Valori in Act IV, sc. iv; p. 262.

- Never fear to weep;

For tears are summer showers to the soul,

To keep it fresh and green.- Candida to Valori in Act IV, sc. iv; p. 264.

- Who loves his country never forfeits heaven.

- Candida to Valori in Act IV, sc. vi; p. 285.

Soliloquies in Song (1882)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1882

- So, timely you came, and well you chose,

You came when most needed, my winter rose.

From the snow I pluck you, and fondly press

Your leaves 'twixt the leaves of my leaflessness.- "My Winter Rose", stanza VII; p. 19.

- Life seems like a haunted wood, where we tremble and crouch and cry.

- "A Woman's Apology", stanza XI; p. 26

- […] faded smiles oft linger in the face,

While grief's first flakes fall silent on the head!- "Unseasonable Snows", line 13; p. 66.

At the Gate of the Convent (1885)

editAt the Gate of the Convent and Other Poems (London: Macmillan and Co., 1885)

- My virgin sense of sound was steeped

In the music of young streams;

And roses through the casement peeped,

And scented all my dreams.- "Prelude", stanza XI; p. ix.

- I love the doubt, the dark, the fear,

That still surroundeth all things here.

I love the mystery, nor seek to solve;

Content to let the stars revolve,

Nor ask to have their meaning clear.

Enough for me, enough to feel;

To let the mystic shadows steal

Into a land whither I cannot follow.

To see the stealthy sunlight leave

Dewy dingle, dappled hollow;

To watch, when falls the hour of eve,

Quiet shadows on a quiet hill;

To watch, to wonder, and be still.- "Hymn to Death", Part IV, line 11; p. 41.

- Why from the plain truth should I shrink?

In woods men feel; in towns they think.

Yet, which is best? Thought, stumbling, plods

Past fallen temples, vanished gods,

Altars unincensed, fanes undecked,

Eternal systems flown or wrecked;

Through trackless centuries that grant

To the poor trudge refreshment scant,

Age after age, pants on to find

A melting mirage of the mind.

But feeling never wanders far,

Content to fare with things that are.- "A Defence of English Spring", p. 58.

- Doth Nature draw me, 'tis because,

Unto my seeming, there doth lurk

A lawlessness about her laws,

More mood than purpose in her work.- "Nature and the Book", stanza XV; p. 67.

- If Nature built by rule and square,

Than man what wiser would she be?

What wins us is her careless care,

And sweet unpunctuality.- "Nature and the Book", stanza XVII; p. 68.

- In vain would science scan and trace

Firmly her aspect. All the while,

There gleams upon her far-off face

A vague unfathomable smile.- "Nature and the Book", Stanza XX; p. 69.

Prince Lucifer (1887)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1887

- O thou sophist, Man!

Reason by reason proved unreasonable

Continues reasoning still! Confronted close,

What is this reason? Like the peacock's tail,

Just useful for a flourish, nothing more;

And when 'tis down, the world goes on the same.- Abdiel in Act I, sc. iii; p. 44.

- Love and naughtiness are always in their teens.

- Crone in Act III, sc. i; p. 63.

- Let Will but set its appetite on war,

And Reason will promptly invent offence,

And furnish blood with arguments.- Abdiel in Act III, sc. iii; p. 80.

- Omit death's certain sharpness, life would lack

The salt that lends it savour.- Lucifer in Act IV, sc. ii; p. 94.

- Death is master of lord and clown.

Close the coffin and hammer it down.- Adam in Act IV, sc. iv; p. 111.

- Public opinion is no more than this,

What people think that other people think.- Lucifer in Act VI, sc. ii; p. 189.

- Who once has doubted never quite believes.

- Eve in Act VI, sc. ii; p. 193.

- Who once believed will never wholly doubt.

- Lucifer in Act VI, sc. ii; p. 193.

Lyrical Poems (1891)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1891

- Is life worth living? Yes, so long

As Spring revives the year,

And hails us with the cuckoo's song,

To show that she is here;- "Is Life Worth Living?", stanza I: p. 158.

- Is life worth living? Yes, so long

As there is wrong to right,

Wail of the weak against the strong,

Or tyranny to fight;- "Is Life Worth Living?", stanza IV; p. 160.

- So long as Faith with Freedom reigns

And loyal Hope survives,

And gracious Charity remains

To leaven lowly lives;

While there is one untrodden tract

For Intellect or Will,

And men are free to think and act,

Life is worth living still.- Is Life Worth Living?", stanza IV; pp. 160–161.

- He is dead already who doth not feel

Life is worth living still.- "Is Life Worth Living?", stanza V; p. 161.

Fortunatus the Pessimist (1892)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1892

- Of all our feigned affections, there is none

So hollow, selfish, and injurious,

As what we christen Patriotism.- Fortunatus in Act I, sc. ii; p. 15.

- 'Tis a world

Where all is bought, and nothing's worth the price.- Fortunatus in Act I, sc. ii; p. 17.

- Towns can be trusted to corrupt themselves.

- Abaddon in Act I, sc. iii; p. 22.

- The Devil is an echo

Of search unsatisfied.- Fortunatus in Act I, sc. iii; p. 35.

- There is no office in this needful world

But dignifies the doer if done well.- Franklin in Act I, sc. iv; p. 65.

- Why should you,

Because the world is foolish, not be wise?- Franklin in Act II, sc. iv; p. 109.

- Imagination should

A reconciler, not a rebel, be,

To teach the heart of man to apprehend

Nature's vicissitudes, and bear his own,

With sympathetic fancy.- Urania in Act IV, sc. ii; p. 178.

The Garden That I Love (1894)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1894

- [T]here is no gardening without humility, an assiduous willingness to learn, and a cheerful readiness to admit that you were mistaken. Nature is continually sending even its oldest scholars to the bottom of the class for some egregious blunder.

- p. 13.

- Once learn how Nature gardens for herself, and you will be able to spare yourself a good deal of trouble.

- p. 22.

- No one can rightly call his garden his own unless he himself made it.

- p. 112.

- A garden that one makes oneself becomes associated with one's personal history and that of one's friends, interwoven with one's tastes, preferences, and character, and constitutes a sort of unwritten, but withal manifest autobiography. Show me your garden, provided it be your own, and I will tell you what you are like.

- p. 112.

- [E]xclusiveness in a garden is a mistake as great as it is in society.

- p. 117.

In Veronica's Garden (1895)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1895

- [H]e who saves an ancient tree does better even than he who plants a new one.

- p. 70.

- Whatever else he may do, a critic reveals and criticises himself.

- p. 91.

- If you are not something of a philosopher,—and by philosophy I understand a serene temper, and the maintaining of an equable mind under the sharpest disappointments,—I do not advise you to cultivate, or at any rate to grow enamoured of, a garden.

- p. 92.

- A writer cannot take his occupation too seriously. He cannot take himself too lightly.

- p. 133.

- [A]mbition should be spoken of as not the last, but the first infirmity of noble minds, of which they gradually purge themselves as they grow more mature.

- p. 139.

Lamia's Winter-Quarters (1898)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1898

- One must be intoxicated by scenery, in order to appreciate it. Tranquil survey is not enough, and scrutinising curiosity is fatal.

- p. 6.

- Men preach Philosophy, women practise it.

- Lamia on p. 66.

- It is always delightful to have one's feelings expressed by some one else in language of enthusiasm one might oneself be afraid to employ.

- p. 68.

- [P]eople who canalise their lives and prearrange their enjoyments lose much of the enchantment which attends the guiding beneficence of chance.

- p. 96.

- Goodnight! Now dwindle wan and low

The embers of the afterglow,

And slowly over leaf and lawn

Is twilight's dewy curtain drawn.- "Goodnight!", p. 163.

Haunts of Ancient Peace (1902)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1902

- All imitation is exaggeration.

- Lamia on p. 4.

- [T]he charm of a half-neglected old garden arises from its having, once upon a time, not been neglected.

- p. 47.

- To homes pervaded by charm, as to works of Art that approach perfection, the more happily constituted minds say 'Yes' without any qualification. The proper homage due to them is absolute assent.

- p. 90.

- A person of the right sort is one who has a solid grasp and realistic apprehension of people and things as they are, an irresistible inclination to transfigure them according to his imagination, and an inexhaustible supply of philosophic humour.

- Lamia on p. 118.

- Hospitality should be accidental, spontaneous, and impulsive, not pre-arranged and calculated.

- p. 121.

The Poet's Diary (1904)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1904

- [T]he Caesars of this world act sagaciously, perhaps, in making as much of their purple as possible. The world is largely governed by tailors and upholsterers.

- p. 155.

- A little knowledge is said to be a dangerous thing, but it is not dangerous to the imagination. Knowledge is to the imagination what fuel is to flame. A little feeds it; a great deal extinguishes it.

- p. 158.

- He was not far wrong who said that, for choice, he would be a beautiful woman from seventeen to thirty, a successful General from thirty to fifty, and a Cardinal for the rest of his days. But of course he was thinking of Cardinals as they were in the days of Leo X, Julius II, and Sextus V, not as they are today, extremely pious and rather pinched for means.

- P. 166.

- He was an Englishman of Englishmen, of the old school of charming manners, flavoured by occasional downrightness of speech.

- P. 171.

- One can put up with, indeed more than put up with, a certain amount of technical carelessness in Poetry, provided it be in other respects of a very high order, as not unoften, for instance, in Shakespeare and Byron. But similar blemishes in a picture would be all but fatal to it in the estimation of connoisseurs, since it would be the first thing that struck them in it.

- p. 179.

- English maidens are, in certain respects, to Italian maidens as moonlight unto sunlight and as water unto wine.

- p. 187.

- [W]henever one wants to cite something wise and true, one has to go either to the ancients or to the eighteenth century for it.

- p. 253.

The Door of Humility (1906)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1906

Where in the lily lurks the mind,

Where in the rose discern the soul?More mindless still, stream, pasture, lake;

The mountains yet more heartless seem. […]It is their silence that appals,

Their aspect motionless that awes,

When searching spirit vainly calls

On the effect to bare the Cause.- "Switzerland", XXII, lines 15–18, 37–40; pp. 53–54.

- If Man makes Conscience, then being good

Is only being worldly wise,

And universal brotherhood

A comfortable compromise.- "Italy", XXXII, line 21; p. 82.

- Doth logic in the lily hide,

And where's the reason in the rose?- "Rome", XLI, line 11; p. 116.

The Garden That I Love: Second Series (1907)

editLondon: Macmillan and Co., 1907

- People living and dead, things past and present, all are contributories to that diminutive stream, oneself; a reflection which is essentially consoling, since it associates one with the sum of things and prevents one from living in barren isolation.

- p. 4.

- Repress your antipathies, cultivate your sympathies.

- p. 4.

- [C]harm appertains to the essence of the person or thing endowed with it. It cannot be acquired, it cannot be got rid of, and its results are produced without effort, since the person who has it cannot help producing them.

- pp. 32–33.

- Women are more frequently charming than men, because they are less self-conscious.

- p. 35.

- [I]n all periods of transitional thought and belief the conscience suffers, since its old sanctions have been removed and none other have yet taken their place. It is undermined without being adequately propped up.

- p. 111.

The Bridling of Pegasus (1910)

editThe Bridling of Pegasus: Prose Papers on Poetry (London: Macmillan and Co., 1910)

- [N]o verse which is unmusical or obscure can be regarded as Poetry, whatever other qualities it may possess.

- "To Sir Alfred C. Lyall" (dedication), p. v.

- Imagination in Poetry, as distinguished from mere Fancy, is the transfiguring of the Real, or actual, into the Ideal.

- "To Sir Alfred C. Lyall" (dedication), p. v.

- The most generous of critics, if he is to be discriminating and just, cannot, let me say again, allow that any verse which is profoundly obscure or utterly unmusical, no matter how intellectual in substance, deserves the appellation of poetry. But on a very thin thread of meaning poetry, or a very fair imitation of it, may be hung by the aid of musical sound.

- "The Essentials of Great Poetry", p. 7.

Disputed

edit- O'er the wires the electric message came,

"He is no better; he is much the same."- On the Illness of the Prince of Wales (1910)

- An 1871 poem on the illness of the Prince of Wales, although there is some doubt that Austin actually wrote this part. That classic compendium "The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse" (2d ed. 1930; Capricorn paperback 1962) includes a dozen quotations from Austin but attributes this particular couplet (p. 17) to a "university poet unknown." It also provides a metrically more accurate first line, "Across the wires the gloomy message came," plus "not" for "no" in the second line.

- The glory of gardening: hands in the dirt, head in the sun, heart with nature. To nurture a garden is to feed not just the body, but the soul.

- Attributed without citation to Austin in Frank and Vicky Giannangelo's Growing with the Seasons (2008), p. 115, and one or two other gardening books, as well as on various internet gardening sites and lists of quotations. However, it is sometimes attributed to Voltaire, and about one-third of the time it is quoted without attribution, at times without even quotation marks. It is nowhere to be found in Austin's The Garden That I Love or any of its five sequels.