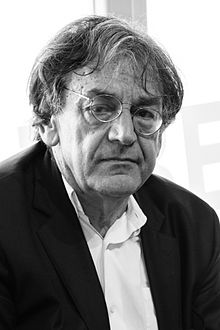

Alain Finkielkraut

French philosopher

Alain Finkielkraut (born June 30, 1949, in Paris) is a French essayist, and son of a Jewish-Polish manufacturer of fine leather goods who had been deported to Auschwitz and survived. He currently teaches at the École polytechnique as professor of the "history of ideas and modernity" in the department of humanities and social sciences.

Quotes

editThe Undoing of Thought (1988)

edit- Translated by D. O’Keefe

- Each man is contained and constrained, on entering social life, to fit his own life in, just as he fits his words and thoughts into a language that was formed without and before him and which is impervious to his power. Entering the game, as it were, whether of belonging to a nation or of using a language, a man enters arrangements which it does not fall to him to determine, but only to learn and respect the rules.

- p. 18.

- DeMaistre and Bonald … wanted to teach men submission, to give them the religion of established power, to substitute, in Bonald’s phrase, “the evidence of authority for the authority of evidence.”

- p. 22.

- For the traditionalists the Enlightenment boiled down to a fatal misunderstanding. All philosophes had been wrong about the nature and also, if one could put it that way, about the sex of prejudice. They had mistaken an earth mother who sustained and inspired her children for a bogeyman of a father. Then, seeking to overthrow this father, they had in reality done away with the mother-figure.

- p. 26.

- According to … the French counterrevolutionaries and German Romantics, … the corpus of prejudices was a country’s cultural treasure, its ancient and tested intelligence, present as the consciousness and guardian of its thought. Prejudices were the “we” of every “I”, the past in the present, the revered vessels of the nation’s memory, its judgements carried from age to age. Pretending to spread enlightenment, the philosophes had set out to extirpate these precious residua. … The result was that they had uprooted men from their culture at the very moment when they bragged of how they would cultivate them. … Convinced that they were emancipating souls, they succeeded only in deracinating them. These calumniators of the commonplace had not freed understanding from its chains, but cut it off from its sources. The individual who, thanks to them, must now cast off childish things, had really abandoned his own nature. … The promises of the cogito were illusory: free from prejudice, cut off from the influence of national idiom, the subject was not free but shrivelled and devitalised. … Everyday opinion should therefore be regarded as the soil where thought was nourished, its hearth and sanctuary, … and not, as the philosophes would have it, as some alien authority which overwhelmed and crushed it. … The cogito needed to be steeped in the profundities of the collective mind; the broken links with the past needed repairing; the quest for independence should yield to that for authenticity. Men should abandon their scepticism and give themselves over to the comforting warmth of majoritarian ideas, bowing down before their infallible authority.

- pp. 25-26.