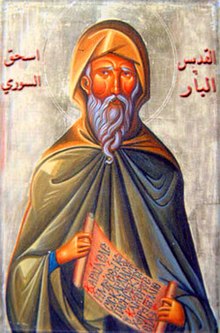

Isaac of Nineveh

Eastern Orthodox saint

Isaac of Nineveh (c. 613 – c. 700), also known as Saint Isaac the Syrian, Abba Isaac, Isaac Syrus and Isaac of Qatar, was a 7th-century Syriac Christian bishop and theologian best remembered for his written works on Christian asceticism.

Isaac of Nineveh's works are divided into the First Part, Second Part (discovered in 1983), Third Part (discovered in the 21st century), and Fifth Part (discovered in the 21st century).

Quotes edit

- What is a charitable heart? It is a heart which is burning with love for the whole creation, for men, for the birds, for the beasts … for all creatures. He who has such a heart cannot see or call to mind a creature without his eyes being filled with tears by reason of the immense compassion which seizes his heart; a heart which is softened and can no longer bear to see or learn from others of any suffering, even the smallest pain being inflicted upon a creature. That is why such a man never ceases to pray for the animals … [He is] … moved by the infinite pity which reigns in the hearts of those who are becoming united with God.

- Mystic Treatises, cited in Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (1976), p. 111; also cited and discussed in A. M. Allchin, The World is a Wedding (1978), p. 85. Quoted in Andrew Linzey, Animal Theology (1994), p. 56.

First Part edit

- The Ascetical Homilies of Saint Isaac the Syrian, second edition (2011), published by the Holy Transfiguration Monastery, Brookline, MA

- In the measure that love for the flesh prevails in you, you can never become brave and dauntless, on account of the host of adversaries that constantly surround the object of your love.

- Homily 1, p. 115

- There is nothing so capable of banishing the inveterate habits of licentiousness from our soul, and of driving away those active memories which rebel in our flesh and produce a turbulent flame, as to immerse oneself in the fervent love of instruction, and to search closely into the depth of the insights of divine Scripture.

- Homily 1, p. 115

- If the heart is not occupied with study, it cannot endure the turbulence of the body's assault.

- Homily 1, p. 116

- But what need is there to speak of the ascetics, those strangers to the world, and of the anchorites, who made the desert a city and a dwelling-place and hostelry of angels? For the angels continually visited these men because their modes of life were so similar; and as being troops of a single Sovereign, at all times they kept company with their comrades-in-arms, that is to say, those who embraced the desert all the days of their life, and took up their abode in mountains and in dens and caves of the earth because of their love for God. And since, having abandoned things earthly, they loved the heavenly and were become imitators of the angels, rightly did those very same holy angels not conceal the sight of themselves from them, and they fulfilled their every wish.

- Homily 5, p. 158

- Moreover, from time to time they [the angels] appeared to them to teach them how they ought to lead their lives.

- Sometimes they clarified certain perplexities for them;

- or sometimes the saints themselves asked them for what was needed.

- And sometimes they guided them when they had strayed along the way;

- or sometimes they came to their rescue when they fell into temptations.

- Sometimes they snatched them from unexpected mishap and peril that overtook them, such as a snake, or a ledge, or a splinter of wood, or a blow from a stone.

- Or sometimes, when the enemy was openly waging war on the saints, they showed themselves visibly to their eyes and said that they were sent to their aid, and brought them confidence, daring, and refreshment by their words.

- At other times they performed healings through them;

- or at times they cured the saints themselves when they fell into certain ailments.

- Sometimes, when their bodies succumbed from lack of food, with a touch of the hand, or with words, they fortified and strengthened them above nature;

- or sometimes, they brought them food, loaves of bread (which were oftentimes even hot), and other things for their nourishment.

- To some of them they foretold their departure;

- and to others, the very manner of their departing.

- Homily 5, pp. 158-9

- The man whose tongue is inclined to silence will acquire a humble discipline in all his habits and will thus gain control over his passions without toil. The passions are uprooted and driven away by unceasing study of God and this is the sword that slays them. Just as the dolphin stirs and swims about when the visible sea is still and calm, so also, when the sea of the heart is tranquil and still from wrath and anger, mysteries and divine revelations are stirred in her at all times to delight her.

- Homily 15, p. 204

- O, how evil for hesychasts is the sight of men and intercourse with them! And in very truth, my brethren, association with those who have relaxed stillness is especially harmful.

- For just as the sudden blast of ice, falling on the buds of the fruit-trees, nips and destroys them, so too, contacts with men, even though they be quite brief and (to all appearance) made for good purpose, wither the bloom of virtue — newly flowering in the temperate air of stillness — which covers with softness and delicacy the fruit-tree of the soul planted by the streams of the waters of repentance.

- And just as the bitterness of the frost, seizing upon new shoots, consumes them, so too does conversation with men seize upon the root of a mind that has begun to sprout the tender blades of the virtues.

- And if the talk of those who have controlled themselves in one particular, but who in another have minor faults, is apt to harm the soul, how much more will the chatter and sight of ignoramuses and fools (not to say of laymen)?

- Homily 19, p. 220

- If you wish to hold fast to stillness, become like the Cherubim, who take no thought for anything of this life, and consider that no one else exists in creation save you yourself and God Whom you heed, even as you have been taught by your fathers who lived before you.

- Homily 21, p. 234

- Abba Arsenius for God’s sake conversed with no one, neither for spiritual profit nor for any other reason. Another man for God’s sake spoke all the day long and received every stranger, but he, on the contrary, chose silence and stillness. For this cause he conversed with the Spirit of God in the midst of the sea of the present life and passed over it with sublime tranquillity in the ship of stillness, even as it was clearly revealed to certain ascetics who inquired of God concerning this. And this is the definition of stillness: silence to all things.

- If in stillness you are found full of turbulence, and you disturb your body by the work of your hands and your soul with cares, then judge for yourself what sort of stillness you are practising, being concerned over many things in order to please God! For it is ridiculous for us to speak of achieving stillness if we do not abandon all things and separate ourselves from every care.

- Homily 21, pp. 234-5

- The sweetness of prayer is one thing, and the divine vision of prayer is another; and the second is more honorable than the first, as a mature man is more perfect than an immature child. Sometimes verses become sweet in a man’s mouth, and during prayer one verse is chanted numberless times and does not permit him to continue to the next, for he can find no satiety therein.

- But sometimes a certain divine vision is born of prayer, and the prayer of a man’s lips is cut short, and stricken with awe by this vision he becomes as it were a body bereft of breath. This (and the like) we call the divine vision of prayer, and not, as fools affirm it to be, some image and form, or a representation of the imagination. And further, in the divine vision of prayer there exist measures and distinctions of gifts.

- Till this point it is still prayer, for the mind has not yet passed to where there is no prayer: that state is above prayer. The movements of the tongue and the heart in prayer are keys; what comes after them, however, is the entrance into the treasury. Here let every mouth, every tongue become silent, and let the heart (the treasurer of the thoughts), and the mind (the ruler of the senses), and the reason (that swift-winged and most shameless bird), and their every device be still. Here let those who seek tarry, for the Master of the house has come.

- Homily 23, pp. 238-9

- On pure prayer: Even as the whole force of the laws and the commandments given by God to men terminate in the purity of the heart, according to the word of the Fathers, so all the modes and forms of prayer which men pray to God terminate in pure prayer. For sighs, prostrations, heartfelt supplications, sweet cries of lamentation, and all the other forms of prayer have, as I have said, their boundary and the extent of their domain in pure prayer. But once the mind crosses this boundary, from the purity of prayer even to that which is within, it no longer possesses prayer, or movement, or weeping, or dominion, or free will, or supplication, or desire, or fervent longing for things hoped for in this life or in the age to come. Therefore, there exists no prayer beyond pure prayer. Every movement and every form of prayer leads the mind this far by the authority of the free will; for this reason there is a struggle in prayer. But beyond this boundary there is awestruck wonder and not prayer. For what pertains to prayer has ceased, while a certain divine vision remains, and the mind does not pray a prayer.

- Homily 23, p. 239

- At this time (when we make our petitions and our supplications to God, and we speak with Him) a man forcefully gathers together all the movements and deliberations [of his soul] and converses with God alone, and his heart is abundantly filled with God. From this he begins to understand incomprehensible things, for the Holy Spirit moves in each man according to his measure, and taking material from that which a man prays, He moves within him, so that during prayer his prayer is bereaved of movement, and his mind is confounded and swallowed up in awestruck wonder, and forgets the very desire of its own entreaty. The mind’s movements are immersed in a profound drunkenness, and it is not in this world; at such a time there will be no distinction between soul and body, nor the remembrance of anything, even as the great and divine Gregory has said: ‘Prayer is the purity of the mind, and it is terminated only by the light of the Holy Trinity through awestruck wonder.’

- Do you see how prayer is terminated through the astonishment of the understanding at that which is begotten of prayer in the mind, as I said at the beginning of this homily and in many other places?

- And again the same Gregory writes: ‘Purity of mind is the lofty flight of the noetic faculties, which resembles the hue of the sky, and upon and through which the light of the Holy Trinity shines at the time of prayer.’

- Homily 23, pp. 244-5

- Therefore, as I have said, one must not call this gift and grace spiritual prayer, but the offspring of pure prayer which is engulfed by the Holy Spirit. At that moment the understanding is yonder, above prayer; and at the discovery of something better, prayer is abandoned. Then the understanding does not pray with prayer, but it gazes in ecstasy at incomprehensible things that lie beyond this mortal world, and it is silenced by its ignorance of all that is found there. This is the unknowing that has been called higher than knowledge. This is the unknowing concerning which it has been said. ‘Blessed is the man who has attained the unknowing that is inseparable from prayer,’ of which may we be deemed worthy by the grace of the only-begotten Son of God.

- Homily 23, pp. 245

- Fire that has flared up in dry wood is difficult to put out, and the flame of divine fervor that descends into the heart of him who has renounced the world will not be extinguished, and it is fiercer than fire.

- Homily 48, p. 365

- When a sailor voyages in the midst of the sea, he watches the stars, and in relation to them he guides his ship until he reaches harbor. But a monk watches prayer, because it sets him right and directs his course to that harbor toward which his discipline should lead. A monk gazes at prayer at all times, so that it might show him an island where he can anchor his ship and take on provisions; then once more he sets his course for another island. Such is the voyage of a monk in this life: he sails from one island to another, that is, from knowledge to knowledge, and by his successive change of islands, that is, of states of knowledge, he progresses until he emerges from the sea and his journey attains to that true city, whose inhabitants no longer engage in commerce but each rests upon his own riches. Blessed is the man who has not lost his course in this vain world, on this great sea. Blessed is the man whose ship has not broken up and who has reached harbor with joy!

- A swimmer dives naked into the sea until he finds a pearl;

- and a wise monk, stripped of everything, journeys through life until he finds in himself the Pearl, Jesus Christ; and when he finds Him, he does not seek to acquire anything else besides Him.

- A pearl is kept in a vault,

- and a solitary’s delight is preserved within stillness.

- A virgin is harmed in gatherings and crowds of people,

- and the mind of a monk in conversation with many men.

- A bird, wherever it may be, hastens back to its nest, there to hatch its young;

- and a monk possessing discernment hastens to his cell, there to produce the fruit of life.

- A serpent guards its head when its body is being crushed,

- and a wise solitary guards his faith at all times, for this is the origin of his life.

- A cloud obscures the sun,

- and much talk obscures the soul which has begun to be illuminated by the divine vision of prayer.

- Homily 48, p. 366

- and much talk obscures the soul which has begun to be illuminated by the divine vision of prayer.

- As grass and fire cannot co-exist in one place,

- so justice and mercy cannot abide in one soul.

- As a grain of sand cannot counterbalance a great quantity of gold,

- so in comparison God’s use of justice cannot counterbalance His mercy.

- As a handful of sand thrown into the great sea,

- so are the sins of all flesh in comparison with the mind of God.

- And just as a strongly flowing spring is not obstructed by a handful of dust,

- so the mercy of the Creator is not stemmed by the vices of His creatures.

- As a man who sows in the sea and expects to reap a harvest,

- so is he who remembers wrongs and prays.

- As the flame of fire cannot be checked from rising upward,

- so the prayers of the merciful are not hindered from ascending to Heaven.

- The current of a stream runs swiftly in a narrow place,

- and likewise the force of anger whenever it finds a place in our mind.

- Homily 51, pp. 379-80

- True is the word of the Lord which declares that no man possessing love for the world can acquire the love of God,

- nor can any who has communion with the world have communion with God,

- nor can any who has concern for the world have concern for God.

- Homily 59, p. 428

- Question Whence does a man perceive that he has attained to humility?

- Answer From the fact that he regards it as odious to please the world either by his association with it or by word, and that the glory of this world is an abomination in his eyes.

- Homily 62, p. 439

- Life in the world is like a manuscript of writings that is still in rough draft. When a man wishes or desires to do so, he can add something or subtract from it, and make changes in the writings. But the life in the world to come is like documents written on clean scrolls and sealed with the royal seal, where no addition or deletion is possible. Therefore, so long as we are found in the midst of change, let us pay heed to ourselves; and while we have power over the manuscript of our life, which we have written by our own hand, let us strive earnestly to add to it by leading a good manner of life, and let us erase from it the failings of our former life. We have power to erase our debts from it as long as we are here. And God will take into account every change we make in it, so that we may be deemed worthy of eternal life before we go before the King and He sets His seal upon it. For so long as we are in this world, God does not affix His seal either to what is good or to what is evil, even up to the moment of our departure when the service of our fatherland is completed and we set out upon our journey.

- Homily 62, p. 442

- Once an elder was asked, ‘What is repentance?’

- And he replied, ‘Repentance is a contrite and humble heart.’

- ‘And what is humility?’

- ‘It is a twofold voluntary death to all things.’

- ‘And what is a merciful heart?’

- ‘It is the heart’s burning for the sake of the entire creation, for men, for birds, for animals, for demons, and for every created thing; and at the recollection and sight of them, the eyes of a merciful man pour forth abundant tears. From the strong and vehement mercy that grips his heart and from his great compassion, his heart is humbled and he cannot bear to hear or to see any injury or slight sorrow in creation. For this reason he offers up prayers with tears continually even for irrational beasts, for the enemies of the truth, and for those who harm him, that they be protected and receive mercy. And in like manner he even prays for the family of reptiles, because of the great compassion that burns without measure in his heart in the likeness of God.’

- Homily 71, p. 491

- The whole length of the night is as the day to them, and the coming of darkness is as the rising of the sun by reason of that hope which exalts their hearts and inebriates them by its meditation.

- Homily 75, p. 518

- ... how they departed and hid themselves in mountains, caves, and in solitary, secluded places, because they saw that this discipline cannot be perfectly accomplished in the society of men on account of the many obstacles; and how these men became dead during their lives for the sake of the life that is in God, wandering in desert regions and amid rocky crags like men who have lost their way, and how the entire world is not comparable to the glory of any one of them.

- Some of them dwelt on sheer and rugged crags, some at the foot of mountains or in deep gorges, some in dens and hollows of the earth, like men who burrow in the ground to lay snares for foxes, some in tombs, and some on the peaks of mountains. Some erected small hovels in the desert and therein passed the rest of their lives. And some built small stone enclosures on the summits of mountains, that is, small cells, and dwelt there as pleasurably as though they were in the palaces of kings. They had no concern for how they could find their livelihood, but only how each of them could please God and bring his struggle to completion in a beautiful way.

- Homily 75, p. 519

Humility edit

- Again he was asked, ‘How can a man acquire humility?’

- And he said:

- ‘By unceasing remembrance of transgressions;

- by expectation of approaching death;

- by inexpensive clothing;

- by always preferring the last place;

- by always running to do the tasks that are the most insignificant and disdainful;

- by not being disobedient;

- by unceasing silence;

- by dislike of gatherings;

- by desiring to be unknown and of no account;

- by never possessing anything at all through self-will;

- by shunning conversation with numerous persons;

- by having no love of material gain;

- and after these things, by raising the mind above the reproach and accusation of every man and above zealotry;

- by not being one whose hand is against every man, and against whom is every man’s hand, but rather one who remains alone, occupied with his own affairs;

- by having no concern for anyone in the world save himself.

- But in brief: exile, poverty, and a solitary life give birth to humility and cleanse the heart.’

- Homily 71, p. 492

- A humble man is never pleased to see gatherings, confused crowds, tumult, shouts and cries, opulence, adornment, and luxury, the cause of insobriety;

- nor does he take pleasure in conversations, assemblies, noise, and the scattering of the senses;

- but above all he chooses to be by himself and to collect himself within himself, being alone in stillness, separated from all creation, and taking heed to himself in a silent place.

- Insignificance, absence of possessions, want and poverty are in every wise beloved by him.

- He is not engaged in manifold and fluctuating affairs, but at all times he desires to be unoccupied and free of the cares and the confusion of the things of this world, that he may keep his thoughts from going outside himself.

- Homily 71, p. 496

- A humble man is never rash, hasty, or perturbed, never has any hot and volatile thoughts, but at all times remains calm. Even if heaven were to fall and cleave to the earth, the humble man would not be dismayed. Not every quiet man is humble, but every humble man is quiet. There is no humble man who is not self-constrained; but you will find many who are self-constrained without being humble. This is also what the meek and humble Lord meant when He said, ‘Learn of Me, for I am meek and humble of heart, and ye shall find rest unto your souls.’ For the humble man is always at rest, because there is nothing that can agitate or shake his mind. Just as no one can frighten a mountain, so the mind of a humble man cannot be frightened. If it be permissible and not incongruous, I should say that the humble man is not of this world. For he is not troubled and altered by sorrows, nor amazed and carried away by joys, but all his gladness and his real rejoicing are in the things of his Master.

- Humility is accompanied by modesty and self-collectedness:

- that is, chastity of the senses;

- a moderated voice;

- mean speech;

- self-belittlement;

- poor raiment;

- a gait that is not pompous;

- a gaze directed toward the earth;

- superabundant mercy;

- easily flowing tears;

- a solitary soul;

- a contrite heart;

- imperturbability to anger;

- undistracted senses;

- few possessions;

- moderation in every need;

- endurance;

- patience;

- fearlessness;

- manliness of heart born of a hatred for this temporal life;

- patient endurance of trials;

- deliberations that are weighty, not light;

- extinction of thoughts;

- guarding of the mysteries of chastity;

- modesty;

- reverence;

- and above all, continually to be still and always to claim ignorance.

- Homily 71, p. 497

Second Part edit

Chapters 1-3 edit

- Chapters 1-3: Brock, Sebastian (translator). (2022). Headings on Spiritual Knowledge: the Second Part, Chapters 1-3. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-702-9

- Prayer does not consist only of the repeating <of words>, but it is <also> the stirrings that well up concerning the <divine> Being from the depth of the mind. As a result of constant meditation on him the mind is at times altered, so that it gazes upon him as though in <awestruck> wonder, its stirrings being united to the Spirit, and in a manner that is ineffable it observes him closely. Blessed is the person who continually tarries by his door without feeling ashamed!

- 1.56, p. 50

- Accordingly, as I have said above, when—as a result of continual converse with him—the soul is moved to enjoyment of the <divine> glory, and is pleased to remain there unceasingly, it has become aware, by the grace of the Holy Spirit, of the very condition in which, at the end, it will be clothed, having achieved this already here in pledge, in so far as the bounds of human nature allow, and having been held worthy of the mode of life of freedom, and tasting it as it were in pledge.

- 2.6, p. 65

- The non-intellectual light is the light that belongs to the elements. Now in the New World a new <kind> of light shines out, and there is no need for the use of anything perceptible or belonging to the elements. Intellectual light <is> the mind illumined with divine knowledge, which is poured out without measure upon the natural world. In the spiritual world <there is> a spiritual light. That <former> darkness does not resemble this <spiritual darkness>, nor does that <former> light resemble this light.

- 3.1.13, pp. 70-1

- The light of contemplation proceeds along with continual stillness and deprivation of outward impressions. For when the mind is empty, it stands continuously in expectation, <waiting to see> what contemplation will dawn for it. Whoever disputes concerning this, not only leads others astray, but he himself has turned aside from the path without being aware of it: he is chasing after a shadow in the imaginations of his intellect!

- 3.1.29, p. 76

- Let the following prayer not cease from your heart night or day: “O Lord, save me from darkness of soul.” For this sums up all prayer that <comes from> knowledge. A darkened soul is a second Sheol, whereas an illumined mind is a companion to the seraphim.

- 3.1.34, p. 77

- Wonder of mind follows on from a solitary abode, for without the distraction <which comes> from <external> necessities and labors, it arouses, through the wisdom to which it gives birth in the mind, fervent and wondrous stirrings.

- 3.1.46, p. 80

- What watering is to plants, exactly the same is continual silence for the growth of knowledge.

- 3.1.47, p. 80

- The “noetic cloud” is the intellect that is smitten with wonder at the spiritual insight that all of a sudden falls upon the soul, and without any movement, establishes the intellect in a state where all visible things are hidden from it in <a state of> non-awareness <and> non-perception of the target of meditation on them, and the mind remains still, like a cloud that surrounds <these> matters and deters any bodily vision.

- 3.1.52, p. 81

- The aim of psalmody should be serene conversation with God by means of calm and unperturbed supplication. Let us not multiply recitation <of Psalms> <in the way> that crazy people do, while wandering about in our thoughts on refuse heaps, and going out from here empty of benefits, <goods which> the discerning intellect is wont to amass at these times.

- 3.1.54, p. 82

- The aim of contemplation of the world to come is to be seen in the coming into being of the holy angels—I am being bold—(a situation) where we are all going to become gods by the grace of our Creator, for that is his intention from the beginning, to bring the entire creation of rational beings to a single even state, without there being any distinction between them and the <angels>, either in a doubled state, or in simple state, without the natural <human> body being treated unfairly: such matters from this point on do not come any more under investigation.

- 3.1.62, p. 84

- How feeble is the power of <pen and> ink and the traces of the letters to indicate in writing the precise nature of <this> action, in comparison with the understanding of those who have been held worthy, with these same actions, of the gift of delight in the spiritual goods that <come> from the abundant grace of God.

- 3.2.18, p. 102

- Solitude lets us share in the divine Mind, and brings us close to limpidity of mind in a short time, without any hindrance.

- 3.2.31, p. 107

- At the time of the sinking of the light and the atmosphere is suffocating, diligently make use of outward means, I mean the bending of the knees, extended supplication, and so on. For all of a sudden the air will clear and the sun will rise once again, unhoped for: sometimes it sends <its> rays even to the midst of the firmament.

- 3.2.32, p. 107

- A desolate place, because of the great barrenness that reigns there, causes us to acquire a deadness of heart <to the world>, and it confirms the heart, mingling it with God because of continually gazing towards him, necessarily, night and day.

- 3.2.33, p. 107

- The state <required> in the soul for truth is the stillness of the intellect, for truth is recognized without any image. Truth consists in clarity of reflection on God, which is established in the intellect.

- 3.2.35, p. 108

- Every reflection that exists is set in motion by the object of the reflection: it makes an imprint in the intellect. But truth, because it is imageless, does not imprint on the intellect in its reflection with any material or composite thought. It has been well said by a certain God-clothed sage, “The intellect that gazes on God is freed from material imprints.” Thus every image that is established in the intellect is less than truth. Reflection on God sets the intellect above images.

- 3.2.36, p. 108

- Wherever you are, be a solitary in your way of thinking—alone and a stranger in heart, not involved <with the world>.

- 3.2.40, p. 111

- Do not reckon the entire mode of life <as a solitary> and the wondrous labors <involved> in it alongside the fact of not being known or thought of, and the flight from everything. The flight from everything also grows and is reinforced by not being recognized.

- 3.2.41, p. 111

- When the intellect has received an awareness of the beauty of its nature, then it grows in the growth of the mystery of the angels and henceforth it is held worthy of participation with the angels in the revelations of the mind, because it has taken its stand in its former rank of the nature of its creation, which was constituted to receive the contemplation of the Prototype.

- 3.2.72, p. 126

- The first delight of the spiritual revelation of the mind is the contemplation of the care of God, whose active power is perceived by the intellect in perceptible actions. The second delight is his care in those who have come into being. The third delight is the contemplation of his creative activity. The fourth delight is the contemplation of his wisdom in them. The might of his unattainable thought <isseen> in the dissimilar variations of his judgements.

With the first perspective <a person> begins to disregard human ways <and means>: this is the first <act of> faith of the intellect.

With the second <perspective> that person relies on, and is strengthened by, confidence in the Maker.

With the third <perspective> he is struck with love of him, like a child who has become aware of his begetter.

On the fourth level, he is hidden in the cloud of his wisdom that is full of discernments.

At the fifth stirring he is immersed in stupefaction at the unattainability of <God’s> intention, which escapes any explanation.- 3.2.73, p. 126-7

- There was <a time> when that there was no name for God, and there is going to be when he will not have one.

- 3.3.1, p. 139

- Some rational beings are without any appellations, and some have many names; those without name are the first. The distinction between appellations <is> in those who are constituted with a body.

- 3.3.3, p. 139

- Just as the non-rational light was entrusted for the distinction of bodies, so with the living Light we see the spiritual distinctions.

- 3.3.4, p. 139

- If the light-giving elements were made for things corporeal for the use of bodies and the discernment of the senses, there is a time when objects discerned by the senses will not exist. It is evident that what came into being for this <purpose> will become superfluous for use.

- 3.3.5, p. 139

- Just as all namings and appellations that concern God were with him at the beginning of creation, so too every name and appellation concerning the intelligible natures took their beginning from the dispensation that is in our world, and these are given names amongst us. In the worlds of the intelligible natures, there is no name, or appellation, or way of calling amongst them concerning each one of the individual <beings>, but they all exist in their world without name or appellation. And all of those numbers without limit of their worlds are natures that are unnumbered. They are recognized by each other outside these distinctions by an exalted knowledge without name or signs. In this mystery all human beings are going to be with them at the resurrection.

- 3.3.6, pp. 139-40

- That the intellect should <find itself> standing during the office or in prayer continually, again and again, all of a sudden involuntarily in <a stale of> stillness for a great period, causing the body to stand erect from its position, this is the great door that has begun to be opened before a person and is the putting into effect of the gift of God: this is not <just> one of the small gifts and partial comforts that apply to everyone. It is after this that we should run, my brother, and seek for this and place it as the aim for our ministry. Also concerning these matters it is not right to make too many words, <so> this suffices on this subject.

- 3.3.38, pp. 149-50

- My brothers, the time of our lives is short, while our craft is long and difficult, but the Good that is promised to us is ineffable.

- 3.3.62, p. 160

- To the extent to which a person is distanced from the settled world, and is withdrawn to the wilderness and wasteland, his heart being aware of the distance from all human nature, so he will receive stillness from thoughts. For in the wilderness, my brother, we do not have much vexation from thoughts, nor do we weary ourselves over much struggle with them. For the very sight of the wilderness naturally deadens the heart in the face of worldly stirrings, and restrains <the heart> from the persistence of thoughts.

- 3.4.51, p. 197

- Just as the sight of someone standing beside smoke cannot become clear unless that person distances himself and moves away from there, so it is not possible to acquire purity of heart and stillness from the thoughts without the solitary life being distanced from the smoke of the world, which wafts in before the senses and blinds the eves of the soul.

- 3.4.52, p. 197

- When the solitary has passed on to another <stage> and becomes aware of the respite from the passions, then he encounters the light of the mind, and through peace from thoughts he is held worthy of concentration of the intellect, and in this concentration of the intellect he enters into this “light of the mind,” of which the fathers speak.

The turbulence <caused> by many thoughts is a sign of a multitude of passions.- 3.4.58, p. 200

- Once a person has, through divine assistance, become recollected from external concerns, and from being “multiple” he has become a “single” person, then from this point on he will begin to see in himself things that are new, and find in himself in a hidden way perceptible intimations and signs. Then, from here he will have a taste, in symbol, of that Renewal of which, at the end of time, the entire community <of human beings>, will be held worthy. This is because many times, including in the midst of the hours of daytime, he perceives in himself that the mind is concentrated into itself, without any concern for itself, through an inexplicable silence. Let the reader understand! This happens to such a person even in the office, and al the time of reading <Scripture>.

The drcams and stirrings during sleep of those who have been held worthy of purity of soul are also separate from those of people who are subject in <their> minds to the passions, or who are still engaged in battle against them.- 3.4.61, p. 201

Chapters 4-41 edit

- Chapters 4-41: Brock, Sebastian (translator). (1995). ‘The Second Part’, Chapters IV-XLI. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 555, Scriptores Syri 225. Louvain: Peeters.

- There is a spiritual perception which is bom out of meditation; this gives delight, joy and exultation to the soul. There is (also) another kind which falls upon a person spontaneously. At the beginning (stages) of this awareness which comes into being as a result of meditation — the result of a love of (sound) doctrine and the exercise of devout conduct — the mind is continually occupied as it meditates on something or other; every now and then, as a result of this excellent meditation concerning the love of God and reflection on the things of God, the person who is occupied in such things out of love of (spiritual) exercise aimed at establishing his personal ministry (to God), finds there is steadily born in him a faculty of spiritual vision of things. Once his soul has been purified a little in devout ministry and alertness, then that spiritual contemplation of sight will every now and then fall upon the soul without any concern on its part: at every moment this person will encounter in his mind some insight, and all of a sudden the mind will stand motionless as though in some divine dark cloud which stuns and silences (the mind).

- 7.1, p. 23

- It can also happen that from time to time a certain stillness, without any insights, can fall upon a person, and the mind is gathered in and dives within itself in ineffable stupefaction; this is the harbour full of rest of which our Fathers speak in their writings, (describing) how on occasion (human) nature enters there, when it has drawn close to the entrance point of a spiritual mode of existence. This (stage) is the beginning of the entry into the third high point, namely the spiritual mode of being. It is with his eyes set on this harbour that the solitary, from the time of his discipleship until he reaches the grave, undertakes all the labour of body and of soul, allowing himself to be buffetted about by all the vicissitudes which these involve. Once the solitary has come near this entrance point, henceforth he will make straight for the harbour as he draws close to the spiritual mode of being; from this point onwards astonishing things take place for him and he receives the pledge of the New World.

- 7.2, pp. 23-4

- Luminous meditation on God is the goal of prayer; or rather, it is the fountainhead of prayers, in that prayer itself ends up in reflection on God.

- 10.38, p. 51

- There are times when a person is transported from prayer to a wondrous meditation on God. And there are times when prayer is born out of meditating on God.

- 10.39, p. 51

- Blessed is God who uses corporeal objects continually to draw us close in a symbolic way to a knowledge of His invisible (nature), sowing and marking out in our minds the recollection of His care for us which has been in operation throughout all generations (thus) binding our minds with love for His hidden Being by means of shapes that are visible.

- 11.31, p. 62

- In the case of a person who has attained to this converse of contemplation in his ascetic way of life, no one (else) at all should pass the night in his dwelling place or cell. (For) during the time of the night, more than at any other time, he should be cut off from everyone and left solitary, in order that stillness may be added to stillness in his soul. For our Saviour too, during the night times, chose deserted places; besides, He honoured and loved stillness at all times, saying ‘Let us go to the wilderness to rest by ourselves’; and ‘He sat down in a boat and went to a deserted region with his disciples’, etc. It was especially at these times that He drew Himself away from people and remained in stillness. Not that He had any need to do this, seeing that He is capable in every place of everything, but even so He nevertheless did not spend the nights at all in inhabited places. ‘He went up to a mountain alone to pray, and when it grew dark He was there alone’. For the instruction of the children of light who would travel afterwards in His footsteps following this new mode of life. He carried out this solitary converse with God. This (converse) which the heavenly ranks alone possess, was also made known to human beings in the Son of God who came down to their abode and indicated to them concerning the ministry of invisible beings, whose task is that they should be stirred by praises of God in that great stillness which is spread over their world, so that, resulting from these (praises) they might be raised up in contemplation towards that glorious Nature of the Trinity, and remain in wonder at the vision of the majesty of that ineffable glory.

- 12.1, pp. 63-4

- The mode of conduct of this (present) life provides (an opening) for the functioning of the senses, while the mode (of the life) to come (leads to) spiritual activation. Whenever a person is held worthy of that knowledge, his limbs all of a sudden cease (to function) and there falls upon him a stillness and silence; for in the conduct of the New Life all use of the senses falls idle. Because even in this world the senses cannot endure to encounter that mystery — even though as it were in some kind of sleep they cease from their activity at a time of repentance, though it is not they which make the encounter but the interior person — ‘may God grant you to know the power of the world to come’, and you will cease henceforth from all engagement with this present life.

- 13.2, p. 65

- When in these matters you receive the power which stems from grace to be bound firmly to their continual stirrings, you will become a man of God and will be close to spiritual things; close, too, to finding that for which you yearn without your being aware of it, namely, the apperception of God, the wonderment of mind that is free of all images, and the spiritual silence of which the Fathers speak. Blessed will you be, and held worthy of the great joy and gladness which exists in our Lord — to whom be praise and honour. And may He perfect us with knowledge of His mysteries, for ever and ever, amen.

- 15.11, p. 87

- On the sequence of ways by which the mind is steered towards the glorious things pertaining to God.

As a result of the mind’s constant meditation and pondering on matters pertaining to the divine Nature, and (as a result of) the batterings and the discipline (effected) by spiritual struggles and conflicts, a certain power accompanying the mind is perceptibly born. And this power (in turn) gives birth in the mind to joy at all times, and by means of joy a person will approach that purity of the thoughts which is called ‘the pure sphere of the natural state’. Then, by means of purity, this person is held worthy of the operation of the Holy Spirit: once he is first purified, then he is sanctified. On occasion this may happen in the middle of reflection on whatever he is occupied with, by means of some luminous stirring that transcends the flesh, when he acquires an inner stillness in God, a semblance of the future state (which consists) in a continual and ineffable rest in God.- 18.3, p. 96

- And when, again, he departs from these things, he is in a stale of joy of soul, and in his reflection and thoughts he is (quite) unlike those who belong to this world, tor he exists henceforth in freedom from thoughts, (a freedom) which is filled with stirrings of knowledge and wonder at God. And because he exists in a (state of) understanding which is more lofty than the soul, and exalted above fear, he is in a state of joy at God in the stirring of his thoughts at all times — as befits the rank of children.

- 20.11, p. 110

- Again, there is the person who has reached perfection on the level of the soul, but who has not yet entered the mode of life of the spirit: only a little of it has begun to stir in him. While he is fully in the mode of life of the soul, every now and then it happens that some stirrings of the spirit arise indistinctly in him, and he begins to perceive in his soul a hidden joy and consolation: like lightning flashes and by way of example, particular mystical insights arise and are set in motion in his mind. At this his heart at once bursts out with joy. Even if (his heart) becomes covered over again, and is blocked off from this, yet it is evident that his mind is nonetheless filled with hope.

- 20.19, p. 111

- Just as there is nothing which resembles God, so there is no ministry or work which resembles converse with God in stillness.

- 30.1, p. 134

- When it sometimes happens that a person is held worthy of prayer of fervour as a result of the surging of grace, then he experiences countless densly-packed stirrings in this prayer: prayers press on each other in a forceful way, (prayers) that are both pure and hot, like coals of fire. In the (midst of these) stirrings a mighty gasp ascends from the depths of the heart: this is mingled with a lowliness which comes from the power of joy. And from (the source) whence these things come, he receives a hidden assistance in his stirrings at these times from the prayer itself, and a burning fire is set in motion in the soul as a result of his joy — until that person is lowered to the abysses in his thoughts.

Thus these stirrings issue forth for him in his prayer (in the form of) pure and forceful prayers, densely-packed and gushing forth in their impetus: they are in the inmost part of the heart, and are accompanied by an unswerving gaze directed towards our Lord. It seems to that person that it is in his very body that he is approaching our Lord at that time, because of the sincerity of the prayer’s thoughts which rise up for him.- 32.1, p. 142

- When he is held worthy of the prayer of understanding, the moment he encounters the smallest word of the prayer immediately the prayer dries up on his mouth and he is completely still of all movements, ending up in motionless silence in both his soul and in his body.

- 32.2, p. 142

- Or maybe there is someone who imagines that the level and the stirring of spiritual prayer consists in one of these things. The person who thinks this should understand that all these things, and countless others like them, (belong) to the level of pure prayer, pure thoughts on the level of the soul, which arise in a person under the title of prayer’. In the life of the spirit, on the other hand, there is no (longer any) prayer. Every kind of prayer that exists (consists of) beauteous thoughts, and these are stirrings on the level of the soul. On the level and in the life of the spirit, there arc no thoughts, no stirring; no. not even any sensation or the slightest movement of the soul concerning anything, for (human) nature completely departs from these things and from all that belongs to itself. (Instead) it remains in a certain ineffable and inexplicable silence, for the working of the Holy Spirit stirs in it, it being raised above the realm of the soul's understanding.

- 32.4, p. 143

- What then shall we say? Where thoughts do not exist, how can one speak any longer of prayer — or of anything else?

- 32.5, p. 143

- There are times when a person sits in a stillness that is guarded and wakeful, and there is no entry or exit for him. But after much converse with the Scriptures, continuous supplication and thanksgiving at his feeble state, with his gaze extended unceasingly towards God's grace, following on after great dejectedness in the stillness, and from that starting point little by little some spaciousness of heart is born, and a germination (takes place) which gives birth to joy from within, even though that (joy) has no origin from that person himself, by some kind of initiating (process of) thought. He is aware that his heart is rejoicing, but he does not know the reason win. For a certain exultation takes hold in the soul, at the enjoyment of which everything that exists and is seen is disregarded, and the mind sees', through its power, whence conies the foundation of that rapture of thought — but why (it occurs) he does not comprehend. He sees that the mind is raised up from association with everything else, is lifted up and finds itself above the world in its upsurge, and (above) the memories which came into being below it. it (now) spurns and removes the whole world of time away, faraway from itself; but it does not discern (any) extension of intellect at (this) leaping of the heart, or (at) the drawing out of the mind during its vexation.

- 34.2, p. 146-7

- When someone reaches insights into creation on the path of his ascetic life, then he is raised up above having prayer set for him within a boundary: for it is superfluous from then onwards for him to put a boundary to prayer by means of (fixed) times or the Hours: his situation has gone beyond its being a case of his praying and giving praise when he (so) wants. From here onwards he finds the senses continuously stilled and the thoughts bound fast with the bonds of wonder: he is continually tilled with a vision replete with the praise that takes place without the tongue’s movement. Sometimes, again, while prayer remains for its part, the intellect is taken away from it as if into heaven, and tears fall like fountains of water, involuntarily soaking the whole face. All this time such a person is serene, still, and filled with a wonder-filled vision. Very often he will not be allowed even to pray: this in truth is the (state of) cessation above prayer when he remains continually in amazement al God’s work of creation — like people who are crazed by wine, (for) this is ‘the wine which causes a person’s heart to rejoice’.

- 35.1, pp. 151

- By prayer I do not mean only the fixed Hours, the Hullale of the psalter and the liturgical hymns. A person who has attained to this understanding (just described) abounds in prayer more than in all the other excellent things. (This prayer) is occasioned by insights, and again is awed by (further) insights and (so) turns to silence, The person who has been (thus) illumined looks into all God’s creation with the eye of the mind and (sees there) God’s providence accompanying all things at all times; (he sees) the supernal care, filled with compassion, which visits creation unceasingly, sometimes under the aspect of adverse events, at others under the aspect of good. And (he grace of God reveals to this person the various kinds of events which are hidden from many people, events which the Creator employs as a wondrous means of assitance in each natural being, whether rational or not possessing a soul; (it reveals too) the unseen reasons behind (all) these vicissitudes which lake place for everything as a result of the provision of love appropriate for each, and that creating and guiding power which guides creation with a care that is utterly astonishing.

- 35.3, p. 152

- When someone receives all the time an awareness of these mysteries, by means of that interior eye which is called spiritual contemplation, which consists in a (mode of) vision provided by grace, then the moment he becomes aware of one of these mysteries, (his) heart is at once rendered serene with a kind of wonder. Not only do the lips cease from the flow of prayer and become still, but the heart loo dries up from (all) thoughts, due to the amazement that alights upon it; and it receives from grace the sweetness of the mysteries of God’s wisdom and love.

- 35.4, pp. 152-3

- This is the consummation of the (ascetic) life in the body (that takes place) on the level of the soul, and the boundary of the spiritual ministry which is perfected in the intellect. Anyone who wishes to attain to a taste of our Lord’s love should ask Him that this door be opened to him. I shall be surprised if, in the case of those who have not approached Him for this (purpose) and who have not become aware of the perception (brought by this mode) of the vision of created things and the workings of providence among them, (if) it is possible for them ever to be aware of that love which captivates the souls of those on whom (this) has alighted.

These arc the things which open up for us the door to that knowledge of truth which is exalted above all (other knowledge), which provides the intellect with a passage across to the glorious mysteries of the divine and revered Nature.- 35.5, p. 153

- It is a matter lor even more astonishment in the case of those who, being outside stillness and great deprivation, have had the boldness to speak and write concerning this mystery of the divine glory in created things. Blessed is the person who has entered this door in the experience of his own soul, for all the power of ink. letters and phrases is loo feeble lo indicate the delight of this mystery.

- 35.6, p. 153

- Now when the intellect has been illumined, even just a little, then it does not greatly need the provision of perceptible words for contemplation. for the natures of created things, and the various divine dispositions in them can serve tor the mind instead of writing. Frequently it will cross over beyond these visible natures and be stirred by insight concerning hidden essences. It can also happen that (the intellect) is raised up by these (essences) and receives the ability to be stirred in its contemplation concerning the revered Creator; this comes through the compassion issuing from that fountain of life which suddenly approaches the intellect’s stirrings, and it peers inside the divine Holy of Holies, in so far as this is permitted to created beings: (this involves) a kind of mystical insight into it. an assured knowledge of the glorious nature of (God’s) Majesty, an apperception of the reality of things which the written word does not dare take down. There are cases where their recording cannot be attempted, for this is not permitted, due to their mystical character; and there are cases where, because they are not written down, they cannot be spoken of either.

- 36.2, p. 157

- So then, let us not attribute to God's actions and His dealings with us any idea of requital. Rather, we should speak of fatherly provision, a wise dispensation, a perfect will which is concerned with our good, and complete love. If it is a case of love, then it is not one of requital; and if it is a case of requital, then it is not one of love. Love, when it operates, is not concerned with the requiting of former things by means of its own good deeds or correction; rather, it looks to what is most advantageous in the future: it examines what is to come, and not things that are past.

- 39.17, p. 170

- By saying that He will even hand us over to burning for the sake of sufferings, torment and all sorts of ills, we are attributing to the divine Nature an enmity towards the very rational beings which He created through grace; the same is true if we say that He acts or thinks with spite and with a vengeful purpose, as though He was avenging Himself. Among all His actions there is none which is not entirely a matter of mercy, love and compassion: this constitutes the beginning and the end of His dealings with us.

- 39.22, p. 172

- And it is clear that He does not abandon them the moment they fall, and that demons will not remain in their demonic state, and sinners (will not remain) in their sins; rather, He is going to bring them to a single equal state of perfection in relationship to His own Being — in a (state) in which the holy angels are now, in perfection of love and a passionless mind. He is going to bring them into that excellency of will, where it will not be as though they were curbed and not <free>, or having stirrings from the Opponent then; rather, (they will be) in a (state of) excelling knowledge, with a mind made mature in the stirrings which partake of the divine outpouring which the blessed Creator is preparing in His grace; they will be perfected in love for Him, with a perfect mind which is above any aberration in all its stirrings.

- 40.4, p. 175

- No part belonging to any single one of (all) rational beings will be lost, as far as God is concerned, in the preparation of that supernal Kingdom which is prepared for all worlds. Because of that goodness of His nature by which He brought the universe into being (and then) bears, guides and provides for the worlds and (all) created things in His immeasurable compassion, He has devised the establishment of the Kingdom of heaven for the entire community of rational beings — even though an intervening time is reserved for the general raising (of all) to the same level.

- 40.7, p. 176

- Let us beware in ourselves, my beloved, and realize that even if Gehenna is subject to a limit, the taste of its experience is most terrible, and the extent of its bounds escapes our very understanding. Let us strive all the more to partake of the taste of God's love for the sake of perpetual reflection on Him, and let us not (have) experience of Gehenna through neglect.

- 41.1, p. 180

Third Part edit

- Hansbury, Mary T. (2016). Isaac the Syrian's Spiritual Works. Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-4632-0593-5.

- The life of solitaries is higher than this world for their way of life is similar to that of the world to come; namely they do not take wife or husband. Instead of this, face to face, they experience intimacy with God. By means of the true icon of the world beyond, they are always united to God in prayer. For prayer more than any other thing, draws the mind to fellowship with God and makes it shine in its ways.

- I.1, 8

- Mysteries are revealed, worlds are transfigured in the mind and thoughts are altered within the flesh, <such that> it no longer seems like flesh. The mind changes abodes and is brought from one to another, not of its own will. In its course, however, it remains gathered and united to the Divine Essence; and the intellect at the end of its course, turns to the first cause and origin. Thus the nature of rational beings observes the sublime order of God’s love, by consideration of the <Divine Essence>.

- I.9, 16

Quotes about Isaac of Nineveh edit

- The Ascetical Homilies of Saint Isaac the Syrian, second edition (2011), published by the Holy Transfiguration Monastery, Brookline, MA

- If all the writings of the desert fathers which teach us concerning watchfulness and prayer were lost and the writings of Abba Isaac the Syrian alone survived, they would suffice to teach one from beginning to end concerning the life of stillness and prayer. They are the Alpha and Omega of the life of watchfulness and interior prayer, and alone suffice to guide one from his first steps to perfection.

- Joseph the Hesychast, in "Dedication to the Blessed and Venerable Elders", p. 7

- I am reading St Isaac the Syrian. I find something true, heroic, spiritual in him; something which transcends space and time. I feel that here, for the first time, is a voice which resonates in the deepest parts of my being, hitherto closed and unknown to me. Although he is so far removed from me in time and space, he has come right into the house of my soul. In a moment of quiet he has spoken to me, sat down beside me. Although I have read so many other things, although I have met so many other people, and though today there are others living around me, no one else has been so discerning. To no one else have I opened the door of my soul in this way. Or to put it better, no one else has shown me in such a brotherly, friendly way that, within myself, within human nature, there is such a door, a door which opens onto a space which is open and unlimited. and no one else has told me this unexpected and ineffable truth, that the whole of this inner world belongs to man.

- Archimandrite Vasileios, Hymn of Entry. Liturgy and Life in the Orthodox Church (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, 1984), pp. 131-2.